Whilst enrolled on an MBA course at Kyiv Mohyla Business School in 2016, Volodymyr Patis, head of the Ukrainian Association of Furniture Producers, had a “light-bulb moment”.

Studying the example of wine production in northern California, he realised that the same principles that underpinned the success of the region’s vineyards could be applied to the business of furniture production in Ukraine.

The ambition was born to turn Rivne, a heavily forested region in western Ukraine, into Ukraine’s furniture Napa Valley. In 2019 the Rivne Furniture Cluster was formed into an association of furniture manufacturers with the backing of the regional government and Ukraine’s Association of Furniture Producers.

Breaking old habits

The basic idea behind the cluster is simple – instead of having many companies each producing different furniture elements, each manufacturer focuses on their own specialisation.

“We had meetings with companies and asked what are you producing? Why are you producing this if you can buy it from this company and it will be cheaper?” said Patis.

The cluster idea rests on businesses being willing to communicate freely between themselves, sharing knowledge and expertise.

Patis said that this was a novel approach for Ukrainian entrepreneurs, scarred by the cut-throat business environment that followed Ukrainian independence.

Sharing information was seen as a surefire way to lose your business. “Because if I [share information], they will take my business away like they always take from me.”

But gradually the logic of the cluster proved itself. One of the cluster’s early success stories was Warmhouse Group, a Rivne company that started out producing equipment for burning up wood scraps from the region’s furniture factories, but which through the cluster spotted an opportunity to produce metal fittings for furniture instead.

Whereas previously Rivne’s furniture makers were making their own metal fittings in-house, or importing them from China, they can now get them more quickly and more cheaply from Rivne.

Early wins

The cluster won a major coup in 2019, when Kronospan, a major Austrian producer of wood panels, invested €200mn in a factory to produce chipboard locally, the main component in wooden furniture. The company has gone on to expand its facilities in the region, investing a total of €565mn over the past five years.

The cluster now produces 62% of Ukraine's plywood, 43% of its chipboard and 72% of its sofa-beds.

Such has been the success of the cluster that the regional administration plans to expand the cluster model. An IT cluster has been established, and a dairy cluster is in the process of being established.

Andrii Liudvichuk, the director of the Furniture Cluster, told bne IntelliNews that it’s not just in Rivne that this approach has taken off: “in the last two or three years there’s been a cluster boom. All the other clusters in Ukraine have roughly the same date of establishment. It’s a very good approach – it's always better to fight together than separately.”

From raw materials to finished goods

Whilst Ukraine has historically been a major exporter of raw materials – primarily metals and agricultural products – the Rivne furniture cluster represents a new direction for the country as it tries to develop its domestic manufacturing sector.

As the country seeks to chart a path out of the destruction and disruption wrought by war, the focus is on processing – turning the country’s abundance of raw materials into finished goods that will bring in more foreign currency earnings and create better paid jobs.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Economy recently unveiled its new strategy for the country’s economic development, and the basic vision is for Ukraine to become an exporter of processed goods to the European Union, and reduce the share of raw materials it exports.

Ukraine’s wood-working industry is one of the areas consistently referred to as having high export potential. The development of the sector has been helped along by a controversial ban on the export of unprocessed timber in 2015, which an EU arbitration panel in 2020 concluded was illegal under the terms of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement.

Patis, however, credited the ban with encouraging international wood-processing companies to invest in Ukraine – “a lot of international companies built their factories on the border with Ukraine, from Romania to Poland – so they take the raw materials but they don’t invest in Ukraine.”

2021 was a record year for Ukraine’s furniture manufacturers, with exports at $1bn. The war forced many producers to close, and caused a 30% drop in exports, but the sector has rebounded – “this year we’re back to pre-war numbers,” said Patis.

Last year saw Ukraine’s furniture makers increase their exports by 15.5%, accounting for products worth a total of $909m. The sector now accounts for 5.7% of Ukraine’s total exports.

The export push: turning west for growth

In Rivne, the focus of the furniture cluster is now squarely on re-orienting the region’s production towards exports.

The economic logic is simple: “If they sell a sofa here for $1,000, they can sell it for $1,500 in Europe,” Andrii Liudvichuk, director of the Furniture Cluster, told bne IntelliNews.

This reorientation represents a major shift for the region’s businesses.

“Before the war, most companies were so focused on the internal market. They really didn't see the opportunity to export. They never tried [because] they think it's something complicated, like higher [maths],” said Liudvichuk.

As Patis pointed out, even right up until the start of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s timber and wood-working industries were more integrated with Russian and Belarusian supply chains than with European ones.

The cluster’s efforts appear to be bearing fruits. A project financed last year by USAID provided training sessions for cluster members, culminating with a buyer’s mission from Polish companies.

Liudvichuk was pleased with the results: “$11mn of investment, an $1.5mn increase in sales, compared to the same period last year, 37 export contracts [and] 60-something people hired during that period.”

But exporting goods is not just a way for companies to earn more money. The war has had a profoundly destabilising effect on Ukraine’s domestic market, meaning that without accessing international markets there is little prospect for growth.

“Our main goal is to grow companies. And without export, you cannot do this, because the local market is not stable,” said Patis.

At the Skloresurs factory, an hour’s drive from Rivne, huge plates of glass are cut into shape for use in construction projects across Ukraine. Over the past thirty years the company has grown from a single workshop to becoming a major supplier of glass for construction products across Ukraine.

Skloresurs started exploring export opportunities in 2019. But despite having all the means and knowhow to start exporting, including its own specialised fleet of trucks and European certification, there was no need to turn to exports due to strong domestic demand: “our [Ukrainian market] was so strong that we preferred to focus mainly in that direction,” Skloresurs founder Oleksandr Kirichuk told bne IntelliNews.

The war has however forced a rethink. “Our sector has declined, because the construction sector is not growing as it was before the war,” said Kirichuk.

But finding customers has been a challenge: “we have all the tools, delivery, packaging, certification, but finding customers, it's problem number one,” said Olha Stepanova, Skloresurs’s head of international affairs.

Developers in Europe are reluctant to sign contracts with Ukrainian companies because of the risk that the war might interrupt production: “when we start working on a project, it could last six months. If there’s a problem in the factory and production stops, it’s a big risk for our customers,” says Kirichuk.

The company joined the Furniture Cluster last year, and – true to the spirit of clusterisation – is now exploring opportunities to supply glass to local furniture producers.

Wartime constraints: power and labour challenges

The war and its knock-on effects are, however, a major drag on the Furniture Cluster’s ambitions, and on manufacturing in Ukraine more broadly.

Governor of Rivne Oblast Oleksandr Koval told bne IntelliNews that power supply is the “number one challenge” facing the region.

Last November, a Russian missile attack on Rivne’s electricity grid left 300,000 residents temporarily without power.

In a sign of how much of a priority they are for the region, electricity supply to major industrial producers such as Kronospan was prioritised even above supply to households.

“When there’s a deficit of electricity, we have to decide whom to give electricity to. Industrial producers have international orders and so on. And then we have to say that households have to wait,” said Koval.

As is the case in practically every sector of Ukraine’s economy, Rivne’s furniture manufacturers are also struggling to hire sufficient staff.

Mobilisation has proved a particular challenge for the furniture industry in Rivne given the factories require highly-skilled workers that cannot be easily replaced.

“I had a session with our members, and I asked them, what problems do you have?

In one hour, I could not move from the question of workforce,” says Liudvichuk.

Polish model

The development of Ukraine’s furniture industry represents a potential pathway to replicate Poland's remarkable economic transformation following EU integration.

"For Ukraine, Poland is a very good example of how to integrate into the European Union," says Serhiy Gemberg, former deputy head of the Rivne regional administration, pointing to Poland's rise to become the world's third-largest furniture exporter.

Poland once competed primarily on low costs – cheap labour and energy that attracted foreign manufacturers looking to relocate production from Western Europe, which today has turned Poland into the world’s fourth largest exporter of furniture.

Ukraine had hoped to follow this playbook, with the Rivne region even winning recognition from the Financial Times a decade ago as one of the top 10 regions globally for operational costs.

But the war has fundamentally altered this equation. "Ten years ago, it was very attractive to move production from the European Union to Ukraine because of cheap electricity and cheap labour. But now that's no longer the case," admitted Gemberg.

And even Poland, an established furniture exporter, is facing a difficult global situation. Polish furniture exports are increasingly being undercut by competition from East Asia – Poland was overtaken by Vietnam’s furniture exports in 2021, and imports of Chinese-produced furniture to Poland surged by 35% in 2024 alone.

In Rivne, the hope is that Ukraine’s furniture makers can cooperate with Poland and integrate into its supply chains, making them both more competitive globally: “Ukrainian companies can be a part of Poland’s export success. Our companies can cooperate with Poland. It can be a win-win,” says Gemberg.

Features

South Korea, the US come together on nuclear deals

South Korean and US companies have signed agreements to advance nuclear energy projects, aiming to meet rising data centre power demands, support AI growth, and strengthen the US nuclear fuel supply chain.

World Bank seems to be having second thoughts about Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam

Ball now in Dushanbe’s court to justify high cost.

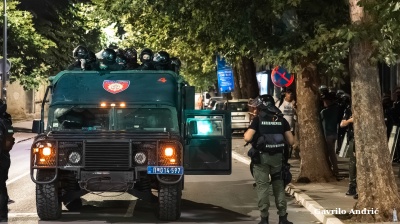

INTERVIEW: From cinema to Serbian police cell in one unlucky “take”

An Italian software engineer caught in Belgrade’s August protests recounts a night of mistaken arrest and police violence in the city’s tense political climate.

_Cropped_1756210594.jpg)

Turkey breaks ground on its section of the TRIPP rail corridor

Turkish project would help make TRIPP the go-to route for Middle Corridor freight.

_1_1756172090.jpg)