PANNIER: Strongman Rahmon’s actions towards Tajikistan’s Pamiri people nothing less than a cultural genocide

The painful losses continue to mount up for the Pamiri people of eastern Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO).

Ever since May 2022, when the Tajik government crushed a peaceful protest in the region and sent in troops to put down what authorities claimed was a terrorist threat, the fortunes of the Pamiris seem to have gone from bad to worse.

Now one of their leading local spiritual leaders, Muzaffar Davlatmirov, has died in prison.

The crackdown

Davlatmirov died on June 26 at Yavan prison, located around 30 kilometres (19 miles) southwest of Dushanbe. He was 61.

Pamir Inside reported his death, saying Davlatmirov suffered health problems related to his diabetes.

Davlatmirov was the khalifa of Turchid district in Khorog, GBAO’s capital.

Khorog, capital of Tajikistan's remote region of GBAO (Credit: GBAO Administration Press Service).

A khalifa is a cleric or spiritual leader in Ismaili Muslim communities. Pamiris are Ismailis, following a Shiite branch of Islam, unlike the majority of Tajiks who are Sunni Muslims.

Davlatmirov was detained as part of the wide-ranging campaign the government launched after coming down hard on the protest in Khorog.

Pamiris who gathered to call for the release of people detained in the wake of a November 2021 protest over the killing of local man were met with tear gas and rubber bullets.

The situation escalated quickly, and authorities initiated a counter-terrorism operation that targeted some of the larger settlements in remote and sparsely-inhabited GBAO.

Many local influential Pamiris were arrested in the weeks that followed. Several were among dozens of Pamiris killed.

State security forces detained Davlatmirov on July 26, 2022. On August 3, he was convicted of publicly calling for the carrying out of extremist actions and sentenced to five years in prison.

Davlatmirov was not allowed to communicate with his family after he was detained, and it is unclear if he had legal counsel at his trial.

Some believe the real reason why Davlatmirov was imprisoned was his performance of funeral services for three of the influential GBAO leaders killed by security forces.

Davlatmirov became the third Pamiri detained in the wake of the 2022 violence to die in prison this year.

Thirty-five-year-old Aslan Gulobov died on June 9. Two days after Davlatmirov was convicted, Gulobov and two others were found guilty of murdering a general of Tajikistan’s security service in GBAO in 2012.

Gulobov was known to have an ulcer and was reportedly experiencing stomach problems for two months before he died.

Activist Kulmamad Pallayev was detained in May 2022, charged with terrorism, premeditated murder, and treason, and sentenced to life in prison. In January this year, the 50-year-old died. He had reportedly been complaining of stomach pains before his death.

Authorities have not publicly commented on any of the three deaths.

In the days and months following the May 2022 violence, hundreds of the most prominent Pamiris were detained – journalists, activists, lawyers, artists, athletes and others.

Many were put on trial in detention centres, behind closed doors. Dozens were given lengthy prison sentences, including life imprisonment, as was the case with Gulobov and Pallayev.

Methodically extinguishing culture

Tajik authorities have methodically worked to extinguish Pamiri culture since the May 2022 security operation.

Pamiris live in areas throughout the Pamir Mountains. For most of their history, the events of the outside world had no effect on the Pamiris’ lives.

Hardly anyone ventured into the rugged and remote areas and in the absence of outside interference, Pamiris developed their own cultures, traditions and languages.

It was not until the very end of the 19th century, when the Russians arrived and established outposts, that regular contact with the outside world started. The Pamiris still live where they have for many centuries, but now their homeland is divided between Tajikistan, China, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Soviet authorities introduced changes, with the use of the Russian language being the most obvious, and built the only two roads that connect to GBAO, one that runs from Kyrgyzstan in the north, and one that runs from Dushanbe in the west.

The Soviet government also helped preserve the local languages and document the Pamiri culture. However, starting in the 1970s, many Pamiris were resettled to help tend agricultural fields in the lowlands of southwestern Tajikistan. They would later suffer severely after independence when conflict erupted.

Tajikistan became independent in late 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed. By spring 1992, civil war broke out. The Pamiris in GBAO sided with the opponents of the government and during the 1992-1997 Tajik civil war, the opposition operated from bases in the mountains of western GBAO.

Khorog and border towns remained under government control due to the presence of Russian border guards based there, but Tajik authorities could not establish any control over GBAO.

This was the situation when the civil war ended in 1997. For the government to claim nominal control over GBAO, Tajik authorities were forced to work out deals with influential local figures, some of whom had been members of the armed opposition during the civil war.

Brutal, unrelenting crackdown: Rahmon (Credit: Tajik presidency).

Tajik President Emomali Rahmon came to power in November 1992 as speaker of parliament. Several years after the signing of the peace agreement, Rahmon started working to neutralise allies he needed during the civil war and political opponents.

Between 1997 and 2022, Rahmon’s government sent troops into GBAO several times to try to gain control over the region. Each time, this sparked violence that ended with a truce essentially preserving the status quo.

GBAO became the only place in Tajikistan where protests against government policies were possible, until May 2022. Since then, the government has not only neutralised any Pamiris who could potentially rally local support, authorities have also worked to reduce the influence of the Pamiris’ spiritual leader, the Aga Khan.

Nearly all the improvements made in GBAO since independence are connected to the Aga Khan and the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN).

The AKDN paid for research into hybrid crops that could grow at high altitudes in GBAO, funded the construction of small power plants and built several important facilities.

In August 2022, the government seized a park in Khorog that the AKDN built and owned. Next to be seized were hotels, a medical centre and other property funded and owned by the AKDN. Tajik authorities also cancelled the licence of the Aga Khan’s lyceum in Khorog, and the government is currently in a court battle to take the University of Central Asia the Aga Khan built in Khorog.

Additionally, in early 2023, the government banned Ismaili home prayers and ordered GBAO residents to remove portraits of the Aga Khan.

On top of everything, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, who had done so much for the Pamiris in GBAO, died in early February this year.

No help in sight

President Rahmon has been able to abuse the Pamiris with hardly any outcry heard from the international community.

Tajikistan is considered something of a front line against terrorist threats emanating from neighbouring Afghanistan. Even democratic governments are concerned about what could happen if Rahmon’s government was overthrown.

Rahmon has hyped up the threat from Afghanistan and taken advantage of the cautious foreign policies of many countries towards Tajikistan to crush domestic opposition, keep the country’s people impoverished, while his family and cronies have grown rich, and now eliminate the Pamiris.

Features

South Korea, the US come together on nuclear deals

South Korean and US companies have signed agreements to advance nuclear energy projects, aiming to meet rising data centre power demands, support AI growth, and strengthen the US nuclear fuel supply chain.

World Bank seems to be having second thoughts about Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam

Ball now in Dushanbe’s court to justify high cost.

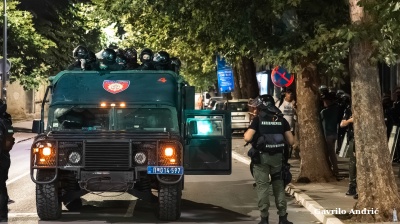

INTERVIEW: From cinema to Serbian police cell in one unlucky “take”

An Italian software engineer caught in Belgrade’s August protests recounts a night of mistaken arrest and police violence in the city’s tense political climate.

_Cropped_1756210594.jpg)

Turkey breaks ground on its section of the TRIPP rail corridor

Turkish project would help make TRIPP the go-to route for Middle Corridor freight.