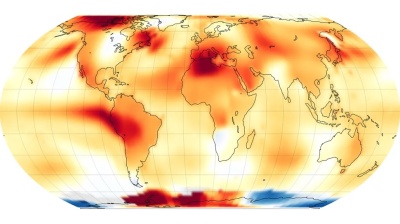

Climate change, especially extreme heatwaves, is already affecting Cairo, and its impact will only intensify in the coming years. Rising temperatures, reduced air quality and unpredictable weather patterns will increasingly challenge daily life across Cairo. Water scarcity may worsen due to lower Nile flow and rising consumption demands. At the same time, urban infrastructure is under threat from extreme weather events.

This year, meteorologists are forecasting a hotter-than-average summer, following a decade of increasingly frequent and intense heatwaves. In the city of over 10mn people — and 22mn in the Greater Cairo Metropolitan Area — climatic shifts are placing new pressures on infrastructure in one of Africa’s largest urban areas.

Cairo’s residents are already taking adaptive actions as temperatures rise. Many people have opted to shift outdoor activities and working hours to the early morning or evening to avoid peak heat. A common practice in the capital is installing rooftop water tanks or using water-saving technologies at home to cope with possible water shortages. Rooftop gardens and other green spaces reduce urban heat and improve air quality.

Cafés in historic areas such as Al-Hussein are bustling with customers seeking shade and refreshment. Lemonade, watermelon juice and sugarcane drinks are staples for beating the heat. During the hot summer, ice cream shops like Mandarine Koueider, Groppi (a historic café in the heart of Cairo founded in 1090), Farghali and juice bars see a surge in demand. Popular cold drinks include sugarcane juice (Kasab), hibiscus (karkadeh), lemon with mint, and tamarind.

In Greater Cairo’s newer suburbs like Madinty, the New Administrative Capital and Tagamu al-Khamis, families flock to shopping malls not to shop, but to cool off in the air conditioning. Malls like City Stars and the Mall of Egypt become de facto public cooling centres during July and August, often overflowing on weekends and public holidays.

Sports clubs such as Al Ahly, El Gezira, Heliopolis and Maadi in Cairo and Sporting in Alexandria offer another escape. Their pools are packed in summer. In poorer districts and villages, it is not uncommon to see children swimming in canals, irrigation channels or large water tanks — despite the safety risks.

On hotter days, many Cairo residents head to the coast for day trips to Ain Sokhna or the North Coast. Low-cost minibuses and ride-sharing apps have made these getaways more accessible, while clubs often organise affordable beach excursions for members. A typical day-use trip costs under EGP500 ($10), offering temporary relief from the stifling city heat.

Environmental dilemmas

Climate change has emerged as one of the most pressing global challenges, posing a significant threat to agricultural productivity and global food security. Though Egypt’s contribution to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is minimal, the country remains acutely vulnerable to climate impacts.

Situated in North Africa and bordered by both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, Egypt’s population and agricultural activity are largely concentrated in the Nile Valley and Delta — areas that represent just 5.5% of the country’s landmass but accommodate over 95% of its inhabitants.

Climate change is already threatening key sectors of Egypt’s economy. Although the country accounts for just 0.7% of global greenhouse gas emissions, its densely populated Nile Delta and Valley make it acutely vulnerable to rising sea levels, desertification and erratic weather patterns. Egypt’s agricultural sector, which employs a quarter of the population, is especially at risk from heat stress and water shortages.

Egypt has witnessed more frequent and intense heatwaves, dust storms, and flash floods over the past decade. Warm nights are increasing, cold nights are declining and rainfall patterns are changing.

With 3,500 km of coastline, Egypt is highly exposed to sea-level rise. A 1 metre rise by 2100 could lead to saltwater intrusion, soil salinisation, reduced agricultural productivity and marine ecosystem degradation. This threatens coastal livelihoods and national food security.

Tourism is a key contributor to Egypt’s economy. However, rising sea levels threaten northern beaches, and coral reefs are at risk of bleaching due to warming seas. Archaeological and historical monuments, exposed to extreme heat and saltwater intrusion, may suffer structural damage. These threats reduce Egypt’s appeal as a tourist destination and pose a risk to cultural heritage preservation.

As well as the land lost to the sea, approximately 3.5 feddans (1.5 hectares) of land are lost every hour due to desertification. With only 4% of land suitable for farming, this significantly impacts Egypt’s ability to sustain food production and maintain environmental balance.

Rising temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns will reduce crop yields and livestock productivity. These changes will especially harm rural communities, potentially increasing poverty and food insecurity.

Egypt relies on the Nile River for 95% of its water supply. Future climate scenarios show uncertainty in river flow, while population growth increases demand. Water scarcity is expected to worsen, requiring flexible and adaptive strategies. The Great Renaissance Dam in Ethiopia is also threatening Egypt’s historical share of Nile water.

Climate change poses direct and indirect risks to human health. Extreme weather can lead to injuries and fatalities, while changing climate conditions support the spread of vector-borne diseases (malaria, dengue and lymphatic filariasis) and waterborne diseases like schistosomiasis. Children under five are particularly vulnerable due to malnutrition and limited access to clean water and nutritious food. Southern Egypt, with its warm temperatures, is especially at risk of disease outbreaks.

Climate change has increasingly strained Cairo and other urban areas, especially with rising rural-to-urban migration. Vulnerable groups such as the poor, elderly and women face greater risks from heatwaves, floods and air pollution. Cities suffer from overuse of energy and water, infrastructure deterioration and inadequate urban planning, particularly in coastal areas prone to flooding.

Adaptation to rising temperatures poses environmental dilemmas. Increased use of air conditioning, while essential for many, risks placing further strain on the electricity grid and raising carbon emissions, unless offset by cleaner energy sources.

Upper Egypt at risk

Upper Egypt is particularly vulnerable to extreme heat due to its desert climate, limited vegetation and already high baseline temperatures. Climate change is expected to increase the frequency, intensity and duration of heatwaves in this region, especially during summer.

Temperatures frequently exceed 45°C, with some areas experiencing prolonged periods of extreme heat. Health risks such as heat exhaustion, dehydration and heatstroke will become more common, especially among outdoor workers, the elderly and children. Agricultural yields may decline, especially for heat-sensitive crops like wheat and vegetables.

In response to the extreme heat waves hitting Egypt in the last decade, many Egyptians have turned to a mix of modern conveniences and traditional habits to stay cool. Some individuals prefer to stay in their air-conditioned rooms or at least sit in front of a fan while spraying themselves with cold water. Portable misting fans and cooling towels are also becoming more common, and sales of such devices usually soar in the summer months. In areas lacking air conditioning, people use fans and wet cloths. Traditional mud houses also provide better insulation.

Although old-fashioned, some Egyptians in densely populated neighbourhoods are returning to sleeping outdoors at night. They spread mattresses or straw mats (called "hasirah") on balconies or rooftops where there is at least some breeze.

People avoid going out between 12 p.m. and 4 p.m., when the heat is at its worst. Instead, errands and appointments are scheduled for early morning or after sunset. Even businesses and small shops may delay their opening hours.

Some professionals and students work online in the summer, when possible, to avoid commuting in the heat. This is more common in Upper Egypt governorates. Cafés with good Wi-Fi and air conditioning, like Beano's or Starbucks, are popular daytime work spots for higher-income groups.

In the cities of Upper Egypt, such as Aswan and Luxor, where hot weather is unbearable, people add ice to their cold beverages, or make popsicles at home using fruit juice and ice cube trays.

Egypt’s climate response

Egypt has taken institutional steps to respond to climate change, including restructuring its National Council for Climate Change, now chaired by the prime minister. The council integrates government ministries, the private sector, civil society, and research centres to coordinate climate action across sectors.

The National Climate Change Strategy 2050, launched in May 2022, outlines five primary goals: achieving sustainable, low-emission economic growth; enhancing resilience and adaptation; improving climate governance; strengthening climate finance infrastructure; and, integrating with broader national development plans.

Egypt’s strategy has helped identify its financial needs and attract climate finance. Notable examples include a $3mn grant from the Green Climate Fund to support Egypt’s National Adaptation Plan, another €150mn joint project with the French Development Agency and the Green Climate Fund, focusing on sustainable tourism, waste management, sanitation and transport. Ongoing partnerships exist with development agencies to implement interactive climate risk maps and resilience-building projects. These efforts illustrate Egypt’s growing commitment to mobilising international support for its national climate priorities, especially those focused on adaptation, emissions reduction and protecting vulnerable populations and ecosystems.

Egypt secured $2.687bn in funding from the Green Climate Fund in 2024 for three projects focused on greening financial systems, smart climate-resilient agriculture, and water infrastructure, according to Minister of Environment Yasmine Fouad. The Ministry of Environment also launched Egypt’s first voluntary carbon market, advanced national transparency reporting and adaptation plans. It contributed to key international climate forums such as the UN General Assembly Climate Week and the African Union’s resilience initiatives. Domestically, the ministry coordinated with parliament to integrate climate change into environmental law, reviewed national climate reports, and worked on a national climate risk map in collaboration with military, meteorological, and water research authorities.

Shift to renewables

Egypt is showing strong ambition to capitalise on the transition to renewable and low-emission energy systems. This transition supports the strategic goal of accelerating the adoption of renewable energy sources, with a target of reaching 42% of electricity generation capacity from renewables by 2030 — an objective the country is on track to achieve through clear policies.

Fouad said recently that Egypt is making substantial progress in addressing climate change risks. She pointed to two critical areas that the Ministry of Environment is working on with relevant authorities; weather forecasting and early warning, which includes efforts to develop an interactive climate change map using approved mathematical models and historical data from the Meteorological Authority and the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation to predict the effects of climate change on different regions in Egypt.

On May 9, Fouad confirmed the urgent need for Egypt to adapt to climate change and to promote development that is resilient to its impacts. She noted that adaptation is no longer a choice but a necessity. She also warned that the cost of delayed action will be much higher in the long run. The minister stressed the importance of focused investment and action on adaptation from both the public and private sectors to reduce climate-related losses.

Despite the urgent need, the minister noted that adaptation efforts are not being implemented at the required scale or pace. Her remarks were made during the session Enhancing Climate Adaptation and Resilience at the Copenhagen Ministerial on Climate, held in Denmark from May 7-8, with the participation of ministers and climate leaders worldwide.

According to the Egyptian Ministry of Environment, Egypt's environmental strategies include creating 30 protected areas covering around 15% of its land. The strategies include mangrove reforestation to safeguard coasts and absorb carbon, wetland restoration in the Nile Delta and North Sinai which is critical for migratory birds, bans on destructive fishing to preserve coral reefs, and the launch of the NWFE platform, which integrates water, food, and energy as a holistic approach to tackling environmental challenges.

This article is part of a series on the impact of the Climate Crisis on major cities around the world.

The other articles in the series are:

Cities confront the rising tide of climate change

Droughts and heatwaves grip Tehran

Two decades of change are testing Tokyo’s resilience

Rising seas threaten India’s coastal cities

Adapting the concrete heart of São Paulo to a changing climate

Mexico's Acapulco still rebuilding as climate disasters mount

Features

Indian used car market in the fast lane

India’s used-car market is expected to see sales volumes surpass 6mn units in the current fiscal year, according to a recent CRISIL Ratings report.

PANNIER: Testing time for exiled Tajik opposition as "reformers" announce breakaway party

Reformers Movement to take on Islamic Renaissance Party in battle to win right to lead fight against strongman Rahmon.

Iranian official's visit to Beirut highlights tensions over Hezbollah

Ali Larijani, Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, arrived in Beirut on August 13 for the second leg of his regional tour, aimed at engaging with Lebanese political leaders.

ASEAN is going nuclear – it's just a matter of time

Across the ASEAN bloc, energy security, surging data-centre demand and net-zero pledges are nudging governments to revisit their nuclear options.