In theory, it is the perfect solution: a grand continental railway slicing across South America, linking the Atlantic coast of Brazil to the Pacific port of Chancay in Peru. In practice, however, the so-called Bi-Oceanic Railway is as much a geopolitical statement as it is a logistical fantasy—an ambitious but perhaps unattainable infrastructure dream struggling against nature, politics, and time.

First floated in 2014 during a BRICS summit, the railway was envisioned as a strategic corridor to bypass the Panama Canal and offer China—and other Asia-Pacific economies—direct access to the Atlantic coast of South America. The logic is sound: if successful, Brazilian commodities could reach Chinese ports up to ten days faster and at significantly reduced costs, with some estimates forecasting savings of $30 per ton on grain exports, as reported by Folha de S.Paulo.

But the path from idea to implementation has proven labyrinthine, to say the least. From its inception, the project has demanded trilateral cooperation between Brazil, Peru and China—three nations with sharply divergent internal political dynamics and vastly unequal infrastructure capabilities. Peru’s government, facing a historic low in public approval (hovering around 2%, according to various national surveys), appears to be using the project as a political life raft rather than a development strategy. As KrASIA reports, this is one of many mega-projects brandished by the Peruvian state to project much-needed modernisation and economic resurgence.

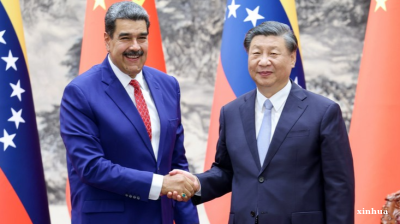

China, meanwhile, plays the long game. Its investment in the $3.4bn Chancay Port—already operational since November 2024 and capable of docking 24,000-TEU megaships—demonstrates a strategic patience shaped by decades of continuity. Chinese President Xi Jinping has framed the port as a “crucial gateway” between Latin America and Asia. The port’s lead operator, state-controlled COSCO Shipping, expects to handle 1.5mn TEUs annually by 2030, with nearly half destined for Chinese shores.

Peru’s Economy Minister Raul Perez Reyes recently announced that the country is planning a trilateral summit with China and Brazil to advance the project, following meetings with China’s ambassador to Peru. The ambassador stated that “a meeting between the countries’ leaders would help define a collaborative framework for the regional rail corridor,” as reported by Reuters.

From a geopolitical perspective, the railway is an ideal complement. In the wake of renewed US-China tensions, exacerbated by President Donald Trump's calls to “retake the Panama Canal" and aggressive trade policies, Beijing has shown increasing interest in securing alternative routes for its vital imports, particularly copper and agricultural commodities, which Peru and Brazil have in abundance.

As reported by Reuters in late 2024, China’s control over Peru’s largest port and its insatiable appetite for copper have shifted trade patterns and diluted US influence in the region. Analysts noted that this growing Chinese presence challenges traditional hemispheric dynamics, especially as China integrates infrastructure diplomacy with long-term geopolitical strategy. This is best exemplified by Beijing's signature Belt and Road initiative, which Peru joined in 2019.

Yet constructing a railway across the South American continent is no small feat. The topographical obstacles alone are staggering. Any viable route must traverse three of the planet’s most complex environments: the Amazon rainforest, the Andes mountains, and the arid coastal deserts of Peru. Planned engineering includes 23 tunnels spanning 112 kilometres through the Andes, and 48 bridges across Amazonian tributaries, as detailed by Mongabay. Environmental groups have already sounded the alarm. Ivaneide Bandeira of the Kanindé Association warns that the project, while avoiding protected areas on paper, will spur agricultural expansion and deforestation in practice.

Moreover, the logistical inconsistencies are glaring. Valor reported that the rail gauge systems of Brazil and Peru are incompatible, prompting Chinese engineers to suggest a hybrid system of standard and metre-gauge tracks. A patchwork network prone to breakdowns or inefficiencies is hardly an appealing proposition for the global shipping industry.

Even the political framework is fraying. Despite years of upbeat summits and declarations—most notably the 2015 Asunción Declaration signed by Brazil, Chile, Argentina and Paraguay—critical sections of the corridor remain unfinished. While some progress has been made, such as the near-completion of roads in Brazil’s Mato Grosso do Sul and the Paraguay River bridge connecting Porto Murtinho and Carmelo Peralta, the full rail integration remains elusive. Bolivia, once considered a central link in the corridor, appears to have been completely sidelined.

Perhaps the greatest illusion of the Bi-Oceanic Railway lies in its presumed urgency. Chinese, Peruvian and Brazilian leaders speak of the project as if it were imminent, yet its original six-year timeline has long expired, and new timelines remain vague or politically motivated. Jorge Viana of Brazil’s trade agency went as far as hailing the corridor as “almost an alternative to the Panama Canal,” but the claim sounds increasingly hollow against the facts on the ground.

In truth, this railway may be more about reshaping hemispheric alliances than moving cargo. China’s economic footprint in Peru has already displaced the United States as the dominant trade partner. According to the Centre for Strategic Studies of the Peruvian Army (CEEPP), China became Peru’s leading trade partner in 2014, overtaking the United States. By 2022, Peruvian exports to China totalled over $20bn, accounting for nearly one-third of the country’s total exports, while imports from China reached $15.7bn. Taken together, the Chancay Port and the railway represent not just logistics infrastructure, but instruments of geopolitical repositioning aimed at tilting the regional balance in Beijing’s favour.

Even so, Peruvian President Dina Boluarte reaffirmed this week that the United States remains “a genuine friend of Peru”. Speaking at the Council of the Americas forum in Lima, she emphasised the historical and economic ties between the two nations, stressing that, despite passing tensions, Peru remains committed to free-market policies and welcoming American investment.

As with many utopian undertakings, the Bi-Oceanic Railway presents a palpable contradiction: it is both incredibly compelling and practically unworkable. It is not just that the geography is hostile, or the politics unstable; it is that the world may have moved on by the time the last rail is laid. Trade patterns shift, technologies evolve, and supply chains reconfigure faster than concrete can be poured in the Amazon.

And yet, China remains unfazed. For a superpower whose planning horizon stretches not to election cycles but dynastic eras, a few decades of uncertainty may be a price worth paying for a corridor that could, in the long term, rewire global trade. As the popular saying now goes in Lima, “from Chancay to Shanghai.” Perhaps someday. But for now, it remains more doggerel poetry than policy.