The currencies of the major emerging markets (EMs) have been gradually depreciating over the last three decades, but the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has accelerated that trend and several currencies are now trading well below their fair value, according to a paper by the Institute of International Finance (IIF).

That normally makes their economies more competitive and leads to a self-correcting surge in exports that bolster the current account. However, this mechanism doesn't seem to be working in Turkey’s case, where the opposite is happening. The global pandemic is only making things worse.

“Major emerging market currencies have been trend-depreciating for several years, but COVID-19 has seen those declines accelerate in 2020. In real terms, we estimate Argentina’s peso is down 50% since 2017, while Brazil’s real and Turkey’s lira are down 40% and 35% respectively over the same period. By any measure, these depreciations are very large and raise the question what medium-term implications – beyond COVID-19 – there may be for activity and the current account,” Robin Brooks, the managing director of IIF and its chief economist, said in a paper put together with his team.

Not all the devaluations are unreasonable, but IIF found nine markets where the currencies were below their fair value even after a correction from being overvalued prior to the depreciation trend kicked in since 1980: Mexico (1995), Indonesia (1998), Russia (1998), Brazil (1999), Argentina (2002), Uruguay (2002), Egypt (2003), Ukraine (2014) and Egypt (2016).

IIF looked at three factors that united these currencies:

- in real, trade-weighted terms the currency falls 30% or more within two years;

- the devaluation is sustained for at least three years, i.e. it is not reversed quickly; and

- the devaluation does not reverse an earlier overvaluation, i.e. the currency drop is not just a reversal of previously high levels.

“There are only nine episodes historically where these criteria are met. Real GDP falls sharply in the year of devaluation, followed by rapid recovery,” says Brooks. “The current account shifts from sizeable deficit to surplus in the wake of devaluation. Argentina and Brazil are seeing current account improvements in line with this historical pattern. Turkey is an outlier, because the current account deficit is widening despite large lira declines.”

Current accounts are usually big winners from a big devaluation as goods become more competitive and exports rise, acting as an automatic curative mechanism to the pain of a collapsing currency.

In Russia the ruble has been hard hit by the collapse of oil prices in March combined with the start of the pandemic in April. The ruble has been sliding continuously over the last few years, falling from RUB56 to the dollar in January 2018 to RUB67 at the start of this year, but has since slumped to almost RUB80 to the dollar in October, before recovering somewhat more recently to RUB75 on the back of Pfizer’s vaccine news.

Likewise, the current account was expected to go into deficit at the start of this year after earning $75bn last year, and did briefly go into the red in the second quarter, but has since recovered to a surplus of $2.5bn in the third quarter and should end the year with a surplus.

Turkey is the exception to the rule, where the lira has crashed from TRY3 to the dollar only two years ago to below TRY8 to the dollar now. Yet as the chart shows, its exports have also crashed and it has a far more diversified and export-led economy than Russia.

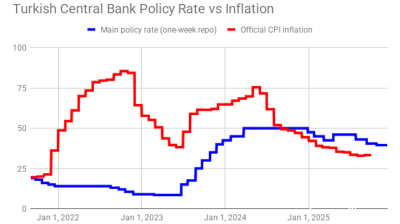

“Why is Turkey such an outlier as far as the current account is concerned? Export volumes soared in the run-up to COVID-19, so the issue is not a lack of export competitiveness,” asks Brooks. “Instead, the issue lies with repeated credit stimuli, which lifted import volumes in 2017 and 2019 and are the reason that import volumes are not contracting more this year.”

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s answer to all economic problems seems to be the same: cut interest rates if possible and pump the economy up with lots of cheap credit. Part of Russia’s current account resilience is that imports have fallen faster than exports, but in Turkey’s case the flood of cheap credit has had the opposite effect.

“It is this import channel that is making Turkey an outlier in an international comparison of import and export volumes and driving persistent depreciation pressure on the lira,” says Brooks. “The bottom line is that the exchange rate channel works for exports, which have risen sharply due to depreciation. Instead, it is the reliance on credit-driven growth that has – so far – prevented current account adjustment.”

Features

Looking back: Prabowo’s first year of populism, growth, and the pursuit of sovereignty

His administration, which began with a promise of pragmatic reform and continuity, has in recent months leaned heavily on populist and interventionist economic policies.

Emerging Europe’s growth holds up but risks loom, says wiiw

Fiscal fragility, weakening industrial demand from Germany, and the prolonged fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine threaten to undermine growth momentum in parts of the region.

The man who sank Iran's Ayandeh Bank

Ali Ansari built an empire from steel pipes to Iran's largest shopping centre before his bank collapsed with $503mn in losses, operating what regulators described as a Ponzi scheme that poisoned Iran's banking sector.

Andaman gas find signals fresh momentum in India’s deepwater exploration

India’s latest gas discovery in the under-explored Andaman-Nicobar Basin could become a turning point for the country’s domestic upstream production and energy security