“There is no money and there will be no money.”

As far as damaging quotes go, the infamous belter by Poland’s one-time finance minister Jacek Rostowski was an absolute train wreck.

Rostowski was reacting to plans by Poland’s right-wing populists from the Law and Justice (PiS) party, who rode to power in 2015 with the promise of universal child benefit for everyone.

PiS put the quote on repeat in that election campaign, which showed Poles had had enough of being told their country was still too poor to guarantee them what had long become standard in Western Europe.

PiS won by a landslide and, three months into their first term, fulfilled their promise, upending years of an anti-welfare stance that lay at the foundation of post-communist Poland, in line with the neo-liberal order that was en vogue with economists at the time.

Deficit… So what?

Nine years later, Poland's centrists are back in power and dare not utter anything even remotely close to Rostowski’s catastrophic line. Running a general government deficit is no longer seen as an irresponsible policy but as an investment in the future, underwritten by the wealth of the Polish economy and its stable growth outlook.

“The macroeconomic situation, which largely determines the tax base, should gradually improve, so we can look with optimism at the future tax stream,” Finance Minister Andrzej Domanski said in the beginning of April.

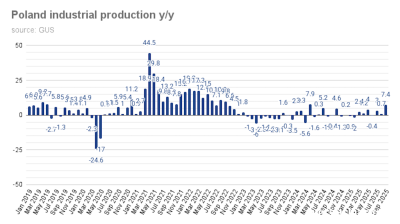

Polish GDP might have expanded just 1.3% year on year in the first quarter, easing slightly versus a gain of 1.6% y/y in the preceding three months, but the outlook is for the economic activity to pick up in the coming quarters.

“We remain comfortable with our forecast for GDP growth of 3% this year,” Capital Economics wrote last week.

"Fiscal policy is set to remain loose and households’ real incomes will continue to recover even if inflation picks up in the second half of this year as we expect,” the London-based consultancy also said.

Polish centrists have grown so deficit-loving, in fact, that when the European Commission said earlier this year it will launch the Excessive Deficit Procedure against Poland, the answer from Warsaw – unlike the last time the procedure kicked in – was pretty much a shrug.

“Poland is in dialogue with the Commission regarding the excessive deficit procedure, aiming to convince Brussels that any recommendations, if issued, should be very lenient, ” Domanski told a meeting at the Atlantic Council, a think-tank, in Washington in April.

Domanski went on to say that Poland’s 2023 deficit came in at 5.1% of GDP because of the economic slowdown last year that saw GDP barely expand at 0.2%.

The slowdown “contributed to the deterioration of headline balance through cyclical factors,” the European Commission said in its latest outlook on Poland’s economy.

“The increasing spending on defence (2.7% of GDP), measures to mitigate the impact of high energy prices (0.6% of GDP) and the budgetary cost of hosting persons fleeing Ukraine (0.3% of GDP), combined with the adverse impact of the 2022 personal income tax reform, contributed to the increase in the deficit,” the Commission also said.

In 2024, the general government deficit is expected to increase to 5.4% of GDP in 2024, with spending on defence set to expand further, as Poland fears Russian aggression.

“We are ready to make some fiscal effort in the coming years, but we will not cut defence spending,” Domanski told the Atlantic Council.

At 4% of GDP, Poland is now Nato’s top defence spender, being wary of Russia and its ally Belarus, with which it has a combined border length of over 650 kilometres.

There is money, after all

Defence and national security – especially with a war waged by one neighbouring country against another neighbouring country – is predictably a politically rewarding topic to exploit.

But the Tusk circle apparently learned at least some lessons from the time in opposition. The projected increase in the deficit is not all due to spending on tanks and missiles to spook Russia.

Early into its term, the government decided to increase the universal allowance for families with children and to raise salaries of teachers by 30% and of public sector officials by 20% – both measures costing the state tens of billions of zloty.

A new programme to support parents of small children aged 1-3 is also kicking in at a cost of some PLN50bn over the next decade.

The net budgetary cost of energy-support measures is projected at 0.5% of GDP, reflecting the extension of most of the support schemes with limited revenues from levies on the windfall profits of energy companies.

Clearly, the shift on the deficit taboo is politically driven, as Tusk is already eyeing the 2027 election, which, the PM has said many times, must not see PiS returning to power.

The government also banks on accelerating economic growth to reduce the deficit automatically, without having to impose significant spending cuts.

Based on unchanged policies, the deficit is forecast to decrease to 4.6% of GDP in 2025 on the back of a cyclical upturn (and the phase-out of energy-support measures).

While the Tusk’s government eventually came to terms with the fact that Poland – with its economy worth nearly €750bn in 2023 – can afford policies its subsequent governments considered unaffordable, the external context is also more favourable than it used to be.

The European Commission has not become more lenient by chance. Facing challenges of increased defence, climate, or healthcare spending, the Eurocrats came to a realisation that making the deficit rule (a bit) less strict is the way forward.

A recent reform of the bloc’s deficit safeguards made it easier for the Tusk administration to brag about maintaining the PiS’ loose fiscal policy line.

While it is “impossible to eliminate the 3% deficit/GDP and the 60% debt/GDP ceilings because they are part of the treaties on the functioning of the EU,” EUnews.it, an Italian news service on European affairs wrote, “member states can choose to embark on a four- or seven-year [deficit and debt] reduction trajectory with a less harsh workload”.

Somewhere down the line, the EU founding treaties will enforce bigger frugality. But most likely, that is, quite unsurprisingly, beyond the scope of the Polish government’s planning and will only become an issue after 2027.

Features

Andaman gas find signals fresh momentum in India’s deepwater exploration

India’s latest gas discovery in the under-explored Andaman-Nicobar Basin could become a turning point for the country’s domestic upstream production and energy security

The fall of Azerbaijan's Grey Cardinal

Ramiz Mehdiyev served as Azerbaijan's Presidential Administration head for 24 consecutive years, making him arguably the most powerful unelected official in post-Soviet Azerbaijan until his dramatic fall from grace.

Ambition, access and acceleration – Uzbekistan’s Startup Garage opens free academy for entrepreneurship

Aim is to train 50,000 young founders by 2030.

Ukraine’s growing energy crisis promises a cold and dark winter

Since the summer, Kyiv has changed tactics. Given the almost complete failure of Western oil sanctions to curb Russian oil exports, it has been targeting Russian oil refineries. The Kremlin has struck back, targeting Ukraine's power system.