Ever since preliminary talks with Turkey on ‘modernising’ its customs union with the European Union were initiated seven years ago, the issue has disappeared and resurfaced with the ebb and flow of a turbulent bilateral EU-Turkey relationship. The project was recently revived – so what’s at stake?

After a new ebb in 2020, the relative stabilisation of bilateral political relations since early 2021 has led the EU’s member states to envisage working again with Ankara to address a common array of topics – not least trade.

In the EU jargon, this is about “positive engagement” with Turkey, a way of pursuing a constructive diplomatic process despite all the other political difficulties.

Talking to MEPs on 8 April, Michael Karnitschnig, the director for external relations at the Secretariat-General of the European Commission, explained: “EU-Turkey relations are in a strange and unsatisfactory situation because the last couple of years have shown that, from managing migration to regional security, from energy to the economy and combating COVID-19, the number of challenges that we face together are literally growing by the day.” Karnitschnig added: “We need to put the EU-Turkey relationship on a firmer footing in order to better pursue these shared interests and tackle shared challenges.”

Late March, member state capitals asked the European Commission to draw up a negotiating mandate for modernisation of the customs union for them to endorse.

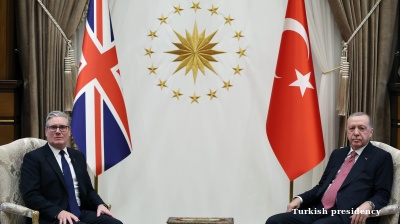

Travelling to Ankara earlier this month, Council President Charles Michel and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen brought with them a package of discussion points and positive engagement proposals to Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Whether the ensuing ‘Sofa Gate’ scandal – in which von der Leyen was consigned to a sofa at the meeting between the two presidents – will ensure the tide turns yet again in EU-Turkey trade politics remains to be seen.

“We have now put something on the table,” said Karnitschnig. “But the incentives are not out there to be pocketed. They are contingent on sustained de-escalation by Turkey, further constructive steps including on the ground, and strengthening of the undeniable positive dynamics of the last couple of months.”

To Karnitschnig, “the ball is now in Ankara’s court.”

Systemic divergence

The decision time for member states to pursue their new Turkey engagement plan is a summit in June. So what is next in terms of the EU-Turkey customs union?

The sense that the 1995 customs union needs to be revamped has been around for many years – and this has been an ongoing Turkish demand.

The deal is partial. It covers only industrial goods and processed foods. The trade rulebook is sparse. Dispute settlement mechanisms are weak, meaning that trade irritants have festered without ever being resolved.

Launching such talks was also seen as a way of making progress on trade and rule-making with Turkey despite a stalled EU accession process.

“After an initially positive trend of increased Turkish alignment to the customs union rules, Turkey has been diverging in an increasingly systemic fashion from these rules over the past years,” said a Commission report circulated to member states last month.

At issue on the EU side are “additional customs duties levied on third-country imports (even when imported from the EU) ... surveillance measures, requiring disclosure of sensitive data, discrimination against EU tractor producers, and excessive testing and certification”.

Furthermore, “Turkey has concluded trade agreements not in line with those of the EU, despite its obligation under the customs union to do so.”

The European Commission had tabled negotiating directives to member states already in 2015 – but the process was stalled in 2016 for a variety of substantive and political reasons, including a new low in Berlin-Ankara relations, leading Germany to block the adoption of the mandate.

Five years have passed and much has happened in the world of trade. The old mandate will need a revamp and the Commission will have to go back at the drawing board.

Offensive interests

What stakeholders and professionals familiar with the matter expect is an expansion of the scope of the customs union to the services sector, to public procurement and to agricultural goods, as well as the inclusion of a new dispute settlement mechanism. Labour rights and environment provisions will also inevitably be included.

EU business interests in Turkey are varied, but definitely include financial services, public works and public procurement contracts in Turkey, temporary labour mobility and patent protection. EU business also wants streamlined, predictable and cost-effective customs procedures – a major irritant in recent years.

On the Turkish side ‘offensive interests’ include better market access for Mediterranean produce, for its construction firms in EU bidding processes (both access to the market and temporary labour mobility), and for its air and road transport operators.

Both sides are looking at the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement finalised last December. Will the UK deal offer precedents or blueprints for the future agreement?

There will probably be no escaping the demands from some member states and from the European Parliament that compliance with Paris Agreement commitments is mandatory and that labour and environment provisions are enforceable in a way that could lead to the reintroduction of trade barriers if there is proven non-compliance.

State aid – which was a major issue with the United Kingdom – could also turn into a complicated negotiation topic with Turkey. The EU has some gripes with Turkish compliance with existing customs union agreement provisions on state aid. It is likely to demand stronger alignment with the EU state aid framework as well as strong, potentially UK-like, dispute settlement provisions.

“The two uncertainties are on the EU’s Green Deal and on digital (issues),” says Sinan Ülgen, a long-standing expert of EU-Turkey trade relations who now heads the Turkish think-tank EDAM.

To Ülgen an EU carbon border measure might be incompatible with the very customs union. In a customs union there are no requirements to prove the origin of a product or of its components. If the EU’s border measure is just limited to a few products such as metals or cement, “maybe it would still be manageable,” says Ülgen. “But if it becomes more than that (...) and integrate final and intermediary products, then it becomes unmanageable within a customs union.”

Digital issues are also contentious. Both EU data protection rules and EU demands that there be no forced data localisation requirements might become a flashpoint. “There is no conversation right now between the EU Turkey on that. If there is a digital component in the customs union, then there will need to be a conversation about data localisation and cross-border data transfers,” says Ülgen.

Whereas this issue might not enter directly into the customs union discussion, the EU’s recent export controls on coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccines – which do not exempt Turkey – are another friction point. The fact that the EU has offered Turkey to hold a ‘high-level dialogue’ on health can be seen as an olive branch.

Iana Dreyer is Editor of borderlex.net, where this article first appeared.

Opinion

Armenia’s painful reorientation toward the West

Yerevan’s drive to break free from its dependency on Moscow is generating profound internal political turbulence and exposing it to new external risks, says a report by the Central Asia‑Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program.

COMMENT: Europe’s “fake it till you make it” war approach cannot hold off Russia’s trillion dollar war machine

In their speeches on the war in Ukraine, European leaders appear like a video clip looped on repeat. Standing before the cameras they declare new packages of support for Kyiv and threaten new measures to pressure Russia as if it was still 2022.

A year after the Novi Sad disaster, Belgrade faces one crisis after another

Serbia’s government is grappling with a convergence of crises which threaten to erode President Aleksandar Vucic’s once-dominant position.

Don’t be fooled, Northern Cyprus’ new president is no opponent of Erdogan, says academic

Turkey’s powers-that-be said to have anticipated that Tufan Erhurman will pose no major threat.