On August 28, at 9:35 am, local time, Uzbekistan’s resident population reached 38 million people.

Central Asia’s population in general has been increasing at a phenomenal rate since its five countries became independent after the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991, but Uzbekistan is the only one of the five to have seen such a high pace of growth.

Half of all people

The current trends indicate that Uzbekistan’s population will account for half of all people in Central Asia within a few years.

Figures from the Soviet Union’s census of 1989 show the Uzbek population standing at 19,810,077 people, so it was somewhere over 20mn when the USSR met its end in late 1991 and the Central Asian countries became independent.

According to Uzbekistan’s State Statistics Committee, the population hit 30mn on April 1, 2013, and by the end of 2018, after an increase of nearly 600,000 during that year, it surpassed 33mn.

In August 2021, the committee released population figures that included demographic data by ethnicity. Those figures showed the population of Uzbekistan as of January 1, 2021, amounting to 34.6mn people, of whom 29.2mn were ethnic Uzbek. The number of ethnic Russians, who in the 1989 census were the second largest ethnic group in Uzbekistan, numbering some 1.65 million, had dropped to 720,300, making Russians the fifth largest ethnic group in Uzbekistan behind Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kazakhs and Karakalpaks. During that same 32-year period, the ethnic Uzbek population expanded from 14mn to over 29mn.

The neighbours

After Uzbekistan, the next most populous country in Central Asia is Kazakhstan, with 20.39mn people. However, the Soviet census of 1989 already put the population at 16.46mn, so the population there increased by less than 25% during the time Uzbekistan’s population nearly doubled.

The population of Tajikistan, meanwhile, more than doubled from 5.1mn in 1989 to 10.6mn as of June 1 this year.

Kyrgyzstan’s population went from 4.58mn in 1989 to 7.31mn as of April 1, 2025.

Turkmenistan claimed in 2023 that its 2022 census showed the country’s population stood at 7.06mn, up from 3,522,717 in the 1989 Soviet census. However, there is great scepticism about the 2023 figure.

Turkmenistan’s economy has been in decline for a decade. There is food rationing, lines outside state stores to obtain bread at subsidised prices, people rummaging through garbage bins looking for something they can hopefully sell, or eat, and beggars, often children and increasingly the elderly, outside bazaars. In such conditions, birthrates tend to be low due to the inability to provide for a large family.

Additionally, many of those who could, have left Turkmenistan. It is difficult to obtain accurate information from Turkmenistan’s government, but some sources put the population at less than three million, others at 5.7mn.

Makings of a demographic timebomb?

Uzbekistan’s population rose by 774,800 people in 2023 and 743,400 in 2024.

According to Tajikistan’s statistics agency, in the first six months of 2025, the Tajik population increased by 98,900 people, taking into account that there were 116,200 births and 17,200 deaths.

Also in the first half of this year, Kazakhstan’s population increased by about 104,400, with roughly 161,200 births and 64,600 deaths registered.

Kyrgyzstan’s birthrate, meanwhile, is decreasing. The country’s statistics committee released figures that showed the birthrate gradually falling from a record of 173,000 in 2019 to some 140,000 in 2024.

When Uzbekistan’s statistics committee announced the population at 38mn, it also mentioned that globally, “the average birth rate is 2.2 children per woman, while in Uzbekistan there are on average 3.5 children per woman.”

The coming age of Uzbekistan in Central Asia?

Leaving aside the dubious official statistics on the population of Turkmenistan, the combined populations of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan amount to just over 38mn people. Given the recent reported rates of population growth in Central Asia, Uzbekistan should therefore have more people than Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan combined before the end of 2026.

This presents the rest of Central Asia with some potential concerns.

Unlike his predecessor Islam Karimov, Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, right, has fostered a spirirt of cooperation across Central Asia, but as demand for the region's natural resources intensifies, his successor might find such harmony difficult to sustain (Credit: Medxim, cc-by-sa 4.0).

With Central Asia’s largest population, bordering every country (plus Afghanistan to the south), Uzbekistan’s first president, Islam Karimov, viewed his country as the regional hegemon.

Uzbekistan was the gateway to Afghanistan during the 1979-1989 Soviet occupation. Plants and factories were built and roadways and railways improved in Uzbekistan to support the troops in Afghanistan, giving Uzbekistan advantages its Central Asian neighbours did not have when independence across the region came. Under Karimov, Uzbekistan also built the largest military in the region.

Karimov’s policies toward his neighbours reflected his vision of Uzbekistan’s supremacy. During his 25 years as leader of independent Uzbekistan, relations with neighbouring states were often strained and borders were closed. Karimov criticised, and sometimes threatened, neighbouring governments over decisions and policy moves that he perceived as harming Uzbekistan’s interests.

Karimov’s successor, current Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who took power in late 2016, has in contrast championed regional cooperation. This is arguably now functioning at a high level not previously seen in the post-Soviet era.

Mirziyoyev is 68 years-old. Changes to Uzbekistan’s constitution allowed him to be elected to a third term in office in 2023. His current term ends in 2030. According to the constitution, Mirziyoyev can run for just one more seven-year term, though leaders in Central Asia, particularly in Uzbekistan, have often manipulated laws and regulations to extend their terms.

However, if Mirziyoyev secures another term in office, he would be 80 when that second seven-year term concluded in 2037.

At the rate of increase experienced during the last few years, Uzbekistan’s population will number 47mn by that time, but the growth has been exponential – it is possible the population will be approaching 50mn.

Central Asia is already suffering clear effects of climate change. Winters are growing shorter, and summers longer. Precipitation is decreasing, record high summer temperatures are increasingly recorded and concerns over water availability are voiced across the region.

Mirziyoyev is friendly with the other Central Asian leaders, but his successor might be more like Karimov. Not only does Uzbekistan have the largest military in Central Asia, it was also the region’s leader for military spending in 2024.

As the competition for diminishing resources hots up in Central Asia, Uzbekistan’s neighbours might have reason to fear its rapid population growth.

Features

US expands oil sanctions on Russia

US President Donald Trump imposed his first sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil companies on October 22, the state-owned Rosneft and the privately-owned Lukoil in the latest flip flop by the US president.

Draghi urges ‘pragmatic federalism’ as EU faces defeat in Ukraine and economic crises

The European Union must embrace “pragmatic federalism” to respond to mounting global and internal challenges, said former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi of Europe’s failure to face an accelerating slide into irrelevance.

US denies negotiating with China over Taiwan, as Beijing presses for reunification

Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, told reporters that the administration of Donald Trump is not contemplating any agreement that would compromise Taiwan’s status.

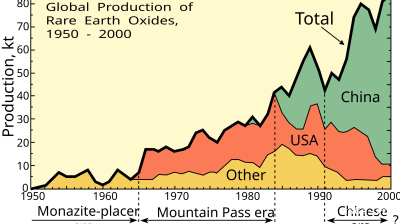

Asian economies weigh their options amid fears of over-reliance on Chinese rare-earths

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.