A year after the Novi Sad train station collapse triggered nationwide protests, Serbia’s government is grappling with a convergence of crises — political, economic and diplomatic — which threaten to erode President Aleksandar Vucic’s once-dominant position.

The protests that began as an outpouring of grief and outrage in response to the deadly infrastructure failure in Novi Sad have evolved into a broader reckoning with a system many Serbians view as brittle and exhausted.

“Serbia is exploding under our asses,” media executive Stan Miller joked in an embarrassing phone call leaked in August, as he discussed plans with state telecom boss Vladimir Lucic to undermine independent media. The offhand remark now captures a country under strain on all fronts.

The political temperature rose this week after a shooting and arson attack outside the Serbian parliament. A 70-year-old former security official opened fire on a camp of pro-government supporters before setting one of the tents ablaze. Vucic condemned the incident as a “terrorist act,” blaming opposition groups for fomenting hatred.

The attack came just over a week before the November 1 anniversary of the Novi Sad disaster, when the collapse of a train station canopy killed 16 people and sparked months of student-led demonstrations, university sit-ins, marches and strikes. Organisers of the anniversary protest, set to take place in Novi Sad, describe it as a “culmination of resistance and remembrance”.

The ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), in power since 2012, has faced its most serious and persistent challenge in over a decade. For many younger Serbians, the movement has evolved beyond the initial demands for accountability, becoming a rallying point for grievances over corruption and the rule of law.

Belgrade is now also feeling the squeeze abroad. The European Parliament this week passed a harshly-worded resolution against the government in Serbia, citing democratic backsliding and alleged human rights abuses. The resolution urges Brussels to consider targeted sanctions unless Serbia aligns with EU foreign policy, especially regarding Russia, and called for early elections and independent oversight of police accused of using excessive force against demonstrators.

Compounding the political turmoil is a looming energy crisis. Moscow’s decision in mid-October to offer only a short-term extension to Serbia’s gas supply contract dashed hopes for a three-year deal. The move followed the imposition of US sanctions on NIS, Serbia’s Gazprom-owned oil firm, and signals Russia’s intent to retain leverage over Belgrade amid ongoing talks on restructuring the company.

Serbia depends on Russia for roughly 90% of its gas imports, most of which transit EU territory via Bulgaria and Hungary. With the EU planning to ban Russian gas transit to third countries, Belgrade faces mounting energy risks. Finance Minister Sinisa Mali called the EU decision “catastrophic” and warned that supply disruptions could occur if neighbouring EU states (namely, Bulgaria) cut off gas flows.

Economic indicators are also weakening. The International Monetary Fund this month slashed Serbia’s 2025 growth forecast to 2.4% from 3.5%, the sharpest downgrade in the Western Balkans. Inflation has remained stubbornly high all year, construction activity has stalled and foreign direct investment plunged by more than half in the first eight months of the year, according to official statistics.

The government’s September decision to impose price caps on essential goods has done little to ease inflationary pressures and may have worsened business sentiment. Retailers report margin losses and supply disruptions, warning of possible store closures and job cuts.

Investor sentiment, already fragile, has been undermined by perceptions of corruption and poor governance following the Novi Sad disaster. The combination of slowing growth, regulatory unpredictability and political unrest could discourage investment at a time when Serbia needs foreign capital to cushion against energy and fiscal shocks.

For years, the government has navigated a delicate balance between East and West — cultivating ties with Moscow and Beijing while maintaining EU accession as its official goal. But that balancing act seems increasingly precarious as Serbia’s domestic fragility collides with external pressure from both directions.

The convergence of political, economic and diplomatic challenges leaves Belgrade following a narrowing path. The Novi Sad anniversary will test whether the government’s authority has been further diminished by recent crises, and whether the protest movement retains the momentum to shape Serbia’s political trajectory over the longer term.

Opinion

Don’t be fooled, Northern Cyprus’ new president is no opponent of Erdogan, says academic

Turkey’s powers-that-be said to have anticipated that Tufan Erhurman will pose no major threat.

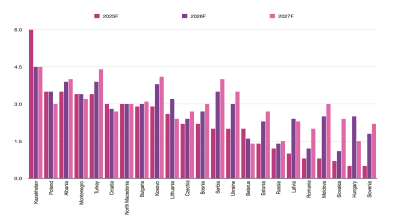

COMMENT: Hungary’s investment slump shows signs of bottoming, but EU tensions still cast a long shadow

Hungary’s economy has fallen behind its Central European peers in recent years, and the root of this underperformance lies in a sharp and protracted collapse in investment. But a possible change of government next year could change things.

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.