The economies of Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe (CESEE) are continuing to show resilience despite the twin pressures of geopolitical uncertainty and slowing global demand, according to the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw). However, fiscal fragility, weakening industrial demand from Germany, and the prolonged fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine threaten to undermine growth momentum in parts of the region.

In its latest autumn forecast, wiiw said the 23 countries it monitors are on track for moderate but stable growth, led by the East European countries and the Western Balkans. Yet the institute warned that widening budget deficits in Romania, Hungary, Slovakia and Poland, coupled with Russia’s hybrid attacks across the region, pose mounting economic risks.

“The main message is the regional outlook is not great … but it’s pretty solid, especially when you think abut what’s happening in Western Europe,” said Richard Grieveson, wiiw’s deputy director and lead author of the report, during a webinar on October 22.

Within the region, “There’s a very mixed picture,” he added. He points out that the EU member states have “tended to underperform” for the last five years, with the exception of Poland. Growth in Russia and Belarus is also expected to be weak.

On the other hand, Kazakhstan, the fastest growing economy in the region “benefits from the political and geoeconomic turmoil. It is receiving investment from all sides,” said Grieveson.

Southeast Europe also, he said, has benefitted from being further from the war in Ukraine and less integrated into German supply chains than Central Europe.

From consumption to investment

For the past decade, growth across the eastern EU has been powered largely by consumer spending, but that is changing, according to wiiw. Cooling real wage growth and higher borrowing costs are forcing households to rein in spending, pushing companies and governments to fill the gap through investment.

"Strong consumption has been the big driver of the last couple of years. It continues to be strong because real wage growth still strong. Labour markets still tight and some are getting tighter, but the the real wage growth is less strong than it was a year ago and will probably decline further,” said Grieveson.

"What we think can take over from consumption is investment,” he added. He pointed out that even after the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Funds end in 2026, new funding is likely to come to the region. FDI continues to flow into the region, albeit at a much lower level now than previously.

A surge in defence spending is also reshaping growth patterns. Nato members in the region are ramping up military budgets, providing an additional annual GDP boost of up to 0.3 percentage points (pp), according to wiiw. Countries such as Poland and the Baltic states stand to gain the most, thanks to their established defence industries.

“Eastern Europeans will gain economically from Europe’s rearmament,” Grieveson said. “It could help them modernise their industrial base and transition towards innovation-driven growth.”

Poland leads, Romania lags

Overall, the eastern EU members are forecast to expand by 2.2% in 2025, slightly below the summer projection, before accelerating to 2.6% in 2026. That compares with growth of just 0.9% in the euro area next year.

Poland is expected to remain the region’s growth leader, expanding by 3.5% in both 2025 and 2026. Croatia and Bulgaria follow closely, with growth near 3%. In contrast, Romania’s outlook has worsened sharply, with wiiw predicting growth of only 0.8% in 2025 and 1.2% in 2026 amid rising fiscal pressures.

The Visegrád Four — Poland, Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary — along with Slovenia, are expected to average growth of 2.5% in 2025, accelerating to 2.9% in 2026.

The Western Balkans continue to perform solidly, with projected growth of 2.5% next year and 3.4% in 2026, though Serbia will see a temporary slowdown. Turkey’s economy is also forecast to remain strong, growing 3.4% in 2025 and 3.9% in 2026.

Bleak prospects

For Ukraine, the outlook remains bleak as the war drags into its fourth year. Economic growth is expected to slow to 2% in 2025 and 3% in 2026, both downward revisions from earlier forecasts.

“The ever-increasing destruction of Ukraine’s infrastructure and the severe labour shortage caused by mobilisation and emigration are dampening growth prospects,” said Olga Pindyuk, wiiw’s Ukraine expert, in a press release from the think-tank. wiiw now assumes the conflict will continue until at least 2027, prolonging the economic strain.

Agricultural exports, a key source of foreign currency, dropped 9% in the first seven months of 2025 due to a poor harvest, though this year’s crop is expected to bring some relief.

“If Russia succeeds in causing widespread power and gas blackouts this winter, another wave of emigration could follow, further weakening the economy,” Pindyuk warned.

Russia’s economy, meanwhile, is stagnating after two strong post-invasion years. Growth is forecast at just 1.2% in 2025, down sharply from 4.3% in 2024, before inching up to 1.4% in 2026.

“The main reason is the Russian central bank’s overly restrictive monetary policy,” said Vasily Astrov, wiiw’s Russia expert. “It has reduced inflation but at the cost of choking credit and investment.”

With interest rates still at 17%, borrowing remains prohibitively expensive. Falling oil prices have also cut into state revenues, while austerity measures aimed at reducing a 2.5% budget deficit are further weighing on demand. Moscow plans to raise VAT and scale back military spending by €6bn in 2026.

“Declining government spending and higher taxes will slow growth even further,” Astrov said.

Hybrid warfare

Beyond the war zones, wiiw highlighted two key risks to regional stability: fiscal imbalances and Russia’s hybrid tactics.

Budget deficits remain stubbornly high across much of the region, forcing governments to weigh spending cuts against the risk of stifling growth.

At the same time, Russia’s sabotage and cyber operations across Eastern Europe are damaging investor confidence. “The region is under hybrid attack from Russia,” said Grieveson.

Despite the headwinds, CESEE economies are expected to continue narrowing the gap with Western Europe, growing roughly twice as fast as the eurozone over the next two years. But the path ahead looks increasingly complex. With consumption weakening, fiscal space tightening and the war in Ukraine grinding on, much of the region’s future growth may depend on whether governments can successfully pivot toward investment-led, innovation-driven development.

Features

Looking back: Prabowo’s first year of populism, growth, and the pursuit of sovereignty

His administration, which began with a promise of pragmatic reform and continuity, has in recent months leaned heavily on populist and interventionist economic policies.

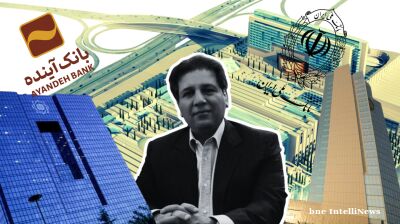

The man who sank Iran's Ayandeh Bank

Ali Ansari built an empire from steel pipes to Iran's largest shopping centre before his bank collapsed with $503mn in losses, operating what regulators described as a Ponzi scheme that poisoned Iran's banking sector.

Andaman gas find signals fresh momentum in India’s deepwater exploration

India’s latest gas discovery in the under-explored Andaman-Nicobar Basin could become a turning point for the country’s domestic upstream production and energy security

The fall of Azerbaijan's Grey Cardinal

Ramiz Mehdiyev served as Azerbaijan's Presidential Administration head for 24 consecutive years, making him arguably the most powerful unelected official in post-Soviet Azerbaijan until his dramatic fall from grace.