As Indonesia’s President Prabowo Subianto marks one year in office this week, the country finds itself navigating between political ambition and economic reality. His administration, which began with a promise of pragmatic reform and continuity, has in recent months leaned heavily on populist and interventionist economic policies. These moves, though aimed at protecting households and boosting growth, risk undermining investor confidence and Indonesia’s long-term fiscal discipline.

According to CNBC Indonesia, Indonesia’s economy showed a mixed performance during Prabowo’s first year. After recording a relatively weak 4.87% year-on-year GDP growth in Q1 2025, down from 5.11% a year earlier, the government responded with an expansive stimulus policy worth more than IDR68 trillion ($4.1bn) over three stages. This included electricity subsidies, wage support, and tax exemptions designed to lift consumer purchasing power.

The response was swift. By the second quarter, growth rebounded to 5.12%, defying market expectations. Yet many economists were puzzled. BCA’s Chief Economist David Sumual described the rebound as “surprising,” given persistently weak household consumption and stagnant manufacturing output. Similarly, Permata Bank’s Faisal Rachman and Maybank Indonesia’s Myrdal Gunarto noted that the stronger-than-expected numbers reflected fiscal stimulus rather than genuine productivity gains, a rebound “fueled by government spending rather than organic recovery.”

Economic populism as policy tool

The Prabowo administration’s economic response has been marked by large-scale social spending, turning populism into an instrument of policy. The government rolled out a range of direct subsidies: discounted electricity rates, extended tax breaks for small businesses, wage subsidies for workers earning up to IDR10mn, and cash transfers under the BLT Kesejahteraan Rakyat programme

Finance Minister Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa defended these initiatives, saying the measures were necessary to “increase money circulation” and stabilise growth momentum. He argued that the combined stimulus could push GDP to 5.7% by the end of 2025, an improvement from earlier projections. In his view, Indonesia’s long-term growth potential remains strong, with the government aiming for an ambitious 8% target to match the trajectories once achieved by Japan, South Korea, and China.

President Prabowo, for his part, insists the policies are not just populist gestures but strategic investments in human capital. In an interview with Forbes, he highlighted the Program Makan Bergizi Gratis (MBG), or Free Nutritious Meals initiative, as a cornerstone of his growth strategy. The program, he claimed, has already created 1.5mn direct jobs through 30,000 community kitchens nationwide. “If people have money, they’ll spend it, on shoes, clothes, fixing their homes,” Prabowo said. “That’s how you multiply growth.”

However, the sustainability of this approach remains in question. Economists warn that Indonesia’s rising fiscal burden could constrain future budgets, especially if social programs expand faster than revenue growth. Overreliance on cash transfers may also mask deeper structural weaknesses, including slow private-sector investment, a subdued manufacturing base, and a limited export rebound.

Food sovereignty: The heart of Prabowo’s national vision

If stimulus defines Prabowo’s short-term agenda, food sovereignty defines his long-term vision. In his first year, the president has repeatedly emphasised self-sufficiency in agriculture as the foundation of national independence, echoing Indonesia’s founding leaders and the developmental philosophy of former President Suharto.

Professor Abdul Haris Fatgehipon, a senior academic at Universitas Negeri Jakarta, told Antaranews that Prabowo has shown “strong consistency” in pursuing food resilience as a matter of sovereignty. “Dependence on imports opens the door to foreign intervention,” he said, praising the president’s inclusive approach that mobilises state enterprises (BUMN), the military (TNI), police, and regional agencies like BIN to reinforce domestic food production.

Prabowo’s agricultural reforms include raising Bulog’s rice purchase price to IDR6,500 per kilogram, expanding fertiliser subsidies accessible via ID cards (KTP), and issuing Presidential Instruction No. 3 of 2025, which brings all agricultural extension workers directly under the Ministry of Agriculture. These policies, according to Prof. Abdul, will accelerate field assistance and strengthen smallholder productivity. The government is also pushing ahead with 48 dam and nine irrigation projects classified as National Strategic Projects (PSN), a sign of the administration’s commitment to rural infrastructure.

Importantly, Prof. Abdul urged that food policy should go beyond rice dependency. He called for greater promotion of local crops such as sago, maize, and tubers, which are better suited to Indonesia’s diverse ecology. “We must not rely entirely on rice,” he said. “Local foods are not only environmentally friendly but also key to restoring Indonesia’s agrarian and maritime identity.” He reminded that shortly after independence, Indonesia once exported 500,000 tonnes of rice to famine-hit India, proof that national strength can come from agricultural self-reliance.

The balancing act ahead

Prabowo’s first year has showcased a leader eager to deliver immediate results, even if it means tilting toward interventionist policies. His mix of fiscal populism, agricultural nationalism, and state-led development reflects a vision of sovereignty that prioritises domestic stability over market orthodoxy.

However, as economists and investors note, the cost of populism can be high. Expanding subsidies, tax exemptions, and cash aid may stimulate consumption in the short run but could weaken fiscal sustainability and investor sentiment over time. The government’s success will depend on whether it can transition from consumption-driven stimulus to productivity-driven growth, through industrial upgrading, export diversification, and innovation.

As President Prabowo enters his second year, the stakes are rising. Competing forces now define Indonesia’s economic narrative: the appeal of populism versus the discipline of reform. Whether Prabowo can balance both will determine if Indonesia’s current momentum evolves into sustained progress, or fades into another cycle of boom and restraint.

Features

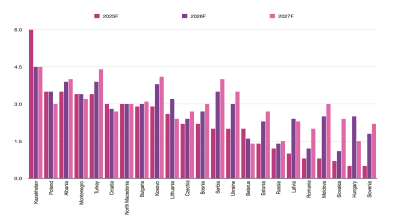

Emerging Europe’s growth holds up but risks loom, says wiiw

Fiscal fragility, weakening industrial demand from Germany, and the prolonged fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine threaten to undermine growth momentum in parts of the region.

The man who sank Iran's Ayandeh Bank

Ali Ansari built an empire from steel pipes to Iran's largest shopping centre before his bank collapsed with $503mn in losses, operating what regulators described as a Ponzi scheme that poisoned Iran's banking sector.

Andaman gas find signals fresh momentum in India’s deepwater exploration

India’s latest gas discovery in the under-explored Andaman-Nicobar Basin could become a turning point for the country’s domestic upstream production and energy security

The fall of Azerbaijan's Grey Cardinal

Ramiz Mehdiyev served as Azerbaijan's Presidential Administration head for 24 consecutive years, making him arguably the most powerful unelected official in post-Soviet Azerbaijan until his dramatic fall from grace.