Beijing’s tightening control over the export of critical minerals has set off alarm bells across Asia, the BRICS nations and beyond, signalling a new front in the global contest for industrial and technological sovereignty.

China’s dominance in the production and processing of rare-earth elements (REEs) - essential for electric vehicles, wind turbines, defence systems and high-end electronics - has long been viewed as a strategic concern. So much so that at the last BRICS summit, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi warned fellow member states of the need for cooperation in ensuring access to supply chains for critical minerals, so that no one country can use such resources for individual gain or as a weapon to limit industrial progress elsewhere. His unnamed ‘one country’ was of course a reference aimed at China.

As such, Beijing’s recent decision to impose export controls on a broad range of rare-earth elements and related technologies, including materials used in high-performance magnets vital to EVs and defence systems, has deepened unease within the region and the bloc. That China could one day also use its access to rare earths to somehow limit renewable energy expansion across Asia only compounds the problem as the region moves away from coal use at breakneck speed.

Increasing numbers of governments around Asia now see these moves as a reflection of China’s near-total dominance of the refining process. By some estimates, Chinese firms control around 90% of the world’s heavy-rare-earth processing capacity. But by couching its export controls in national-security terms, Beijing has positioned itself not just as a supplier but as a gatekeeper of global industrial development. This has not gone down well – even with traditional allies.

Broader Asian concerns

Beyond the BRICS framework, China’s dominance in rare earths reverberates across Asia, where several countries are racing to establish or expand their own capacity in mining, refining and downstream manufacturing. The structural imbalance in which China not only mines but also refines most of the world’s rare-earth ores, has prompted a renewed search for alternatives and soul searching by China’s neighbours.

Myanmar as one of the few other Asian nations with notable reserves of heavy rare earths, particularly dysprosium and terbium already exports much of its output to China for processing, underscoring Beijing’s grip over the value chain. Environmental degradation and informal mining practices in Myanmar have also raised sustainability concerns, complicating efforts to formalise the sector, especially at a time the ruling junta is engaged in a costly civil war.

Vietnam, meanwhile, has emerged as a potential regional counterweight. Its Lai Chau and Dong Pao deposits are seen as among the largest outside China. To this end, despite ideological similarities to its northern neighbour, Hanoi has been courting Japanese, Korean and Western investors to develop refining capacity, though progress remains slow due to high capital costs and the technological sophistication required for processing.

India too possesses considerable reserves of monazite sands - a source of light rare earths - primarily along its southern and eastern coasts. Yet the country’s processing and magnet-manufacturing infrastructure remains underdeveloped and thus very limited. As a result, India still imports refined materials from China. New Delhi has, however, now launched initiatives under its “Atmanirbhar Bharat” (self-reliant India) campaign to promote domestic refining, but progress will take time.

Elsewhere in Asia, Malaysia hosts the only significant rare-earth processing facility outside China – albeit operated by Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths. Despite local opposition over radioactive waste concerns, the facility demonstrates the importance of diversifying the refining network.

Indonesia and Thailand have also identified potential reserves, while Japan and South Korea are investing in recycling technologies and strategic stockpiles to hedge against supply shocks – but this too, like the efforts in India, will take time.

Necessary recalibration

For the BRICS bloc too, the rare-earth question goes to the heart of industrial sovereignty. The group’s collective challenge is not merely to mine more but to process and manufacture more.

India’s emphasis on securing partnerships and avoiding the “weaponisation” of resources signals a shift towards cooperative industrial policies among emerging economies. Brazil and South Africa, both with untapped mineral reserves of their own, are now exploring joint ventures with Asian partners to develop refining capabilities, while Russia - already a significant producer of some critical minerals - is already thought to be looking eastwards to deepen collaboration.

Yet the road to diversification is steep. Rare-earth processing involves complex chemical separation and high environmental costs. Even if new mines are developed across Asia tomorrow, refining capacity and technological know-how remain heavily concentrated in China. As such, any short-term disruption in Chinese supply chains could – and is already in some sectors - sending shockwaves across global industries.

The wider concern right now, as analysts note, is that such long-term dependencies cannot suddenly be reversed. Asia and the world is only now learning to live with, and hedge against, China’s rare-earth dominance.

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.

Features

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Espionage claims thrown at Imamoglu mean relief at dismissal of CHP court case is short-lived

Wife of Erdogan opponent mocks regime, saying it is also alleged that her husband “set Rome on fire”. Demands investigation.

Turkmenistan’s TAPI gas pipeline takes off

Turkmenistan's 1,800km TAPI gas pipeline breaks ground after 30 years with first 14km completed into Afghanistan, aiming to deliver 33bcm annually to Pakistan and India by 2027 despite geopolitical hurdles.

Looking back: Prabowo’s first year of populism, growth, and the pursuit of sovereignty

His administration, which began with a promise of pragmatic reform and continuity, has in recent months leaned heavily on populist and interventionist economic policies.

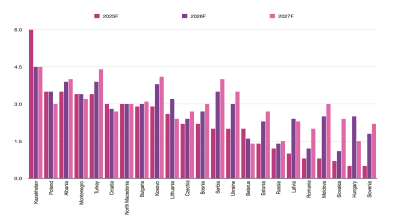

Emerging Europe’s growth holds up but risks loom, says wiiw

Fiscal fragility, weakening industrial demand from Germany, and the prolonged fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine threaten to undermine growth momentum in parts of the region.