The US Navy deployment in the Caribbean and air strikes against three alleged drug boats from Venezuela have nothing to do with counter-narcotics. Instead, they are about political posturing and pushing for regime change in Caracas, with potentially grave consequences for foreign policy, as I presented in a series of investigative articles for Guacamaya.

Venezuela is not a major producer or transit country for drugs consumed in the US. But it remains rich in natural resources, with large reserves of hydrocarbons and metals, keeping it firmly on Washington's radar. An elaborate narrative of a Venezuelan "narco-state" and a "Cartel de los Soles" has thus been manufactured to justify military action.

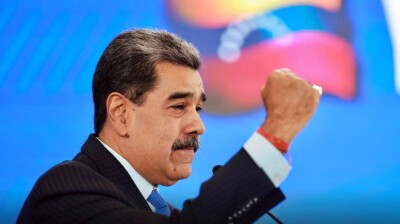

Looking at different scenarios, options now include drone strikes within Venezuelan territory, while an invasion appears implausible. Negotiations are likely to follow, though their objective remains unclear. Will President Donald Trump force early elections in Venezuela? Will he seek to oust Nicolás Maduro immediately? Or will the White House focus on advancing US interests without much consideration for South American politics?

The Cartel of the Suns

The State and Justice departments' accusations that Maduro heads the Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua are, to begin with, unfounded. While cocaine trafficking and corruption do exist in Venezuela, there is no evidence of the hierarchical, structured criminal organisation alleged.

Instead, we see a regional pattern amplified by Venezuela's economic and institutional crisis. Organised crime groups exploit porous borders, extreme inequality, social exclusion and geographical proximity to the US—cocaine's main market. These conditions create fertile ground for highly profitable illicit economies. Cocaine is just one, alongside illegal mining, human trafficking and other activities.

The accusations claim Maduro is flooding the US with cocaine and weapons. The second allegation needs no rebuttal. As for the first, the Drug Enforcement Administration itself states that 5% of Colombian cocaine transits through Venezuela. While some estimates are slightly higher, Venezuela, whose domestic coca production is negligible, is not the central trafficking hub that would pose a threat to US public health.

The main transit route is the Eastern Pacific, which in 2019 carried 74% of cocaine leaving South America. The Western Caribbean accounts for 16%, while the Caribbean Corridor—where the US Navy is now deployed—accounts for just 8%. A smaller amount moves overland through Panama.

Curiously, cocaine is back in the spotlight even though opioids and fentanyl are the main narcotics devastating American cities today, the latter accounting for 70% of overdose deaths.

A political narrative to justify military intervention

The recent deployment does not stem from US government incompetence. Clear political motives explain why the Cartel de los Soles narrative is being promoted. This is not like President George W Bush's 2003 invasion of Iraq based on erroneous intelligence that later proved entirely fabricated.

According to David Smilde, a sociology professor at Tulane University, "This phenomenon is a classic way in which displaced or marginalised elites seek to gain power in authoritarian contexts, especially when unable to do so through elections or protest movements."

"They have tried this for years, arguing Venezuela harbours terrorist camps or Iranian missiles, threatens regional stability, or poses a national security threat to the US. They use their access to international media and sympathetic think-tanks to push these narratives."

The Cartel de los Soles story gained traction in Washington, specifically in 2020 and again in 2025, for a reason. During Trump's first term, the US openly pursued regime change in Venezuela, led by foreign policy hawks including John Bolton, Elliott Abrams, Mauricio Claver-Carone and Mike Pompeo. But while 2020 began with Maduro's indictment and a $15mn bounty for his arrest (now raised to $50mn), it ended with Trump expressing regret over supporting Juan Guaidó's interim government and openness to meeting the Venezuelan strongman, as reported by Axios.

This time around, the narrative is being spearheaded by National Security Advisor and Secretary of State Marco Rubio and his South Florida congressional allies. Their longstanding objective – and personal mission – is liberating Cuba from communist rule, and they view removing Maduro as crucial to this goal. However, the America First rhetoric sits uneasily with regime change, and Trump has downplayed its very possibility. Rubio has therefore deftly reframed his discourse to align with campaign promises to use the military against drug cartels: a far more popular idea than repeating an Iraq scenario.

Strikes against cartels, without necessarily ousting Maduro, offer common ground for neoconservatives and America First proponents. Trump campaigned on using the military against Mexican cartels, after all. Meanwhile, Rubio and his allies can attempt to use the Navy deployment for their own purposes.

This creates contradictions for the Republican South Florida electoral base. Many Latino voters there view the termination of Temporary Protected Status and Humanitarian Parole for Cubans and Venezuelans as a betrayal. And for Trump, designating Tren de Aragua a foreign terrorist organisation and linking it to Maduro was meant to accelerate deportations, not justify intervention in Venezuela. As the administration continues repatriation flights to Maiquetía International Airport and pushes to terminate special protections for Venezuelan immigrants, Rubio and his allies double down on anti-Maduro rhetoric.

Geoff Ramsey, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, sees an approach "for the cameras" with the military deployment and strike against an alleged drug boat, while the administration also "advances US interests in immigration, energy and other strategic issues". The Cuban-Venezuelan base is also unhappy with the licence allowing Chevron's return to operations in Venezuela, issued on July 24. Not coincidentally, the following day the Treasury sanctioned the Cartel de los Soles as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist.

What comes next?

Further US military action appears highly likely. An Axios report suggests Washington officials are considering everything from air strikes inside Venezuela to a Panama-style invasion. While boots on the ground seem far-fetched, drone strikes against alleged drug laboratories or warehouses in remote areas cannot be ruled out.

Any attack inside Venezuelan territory would constitute a major escalation with unforeseen consequences. The hope is that an attack would terrorise the regime, particularly the military, prompting either Maduro or military leadership to negotiate.

The risk, though, is that Chavismo closes ranks under pressure, as it did when Venezuela faced political isolation and sanctions in 2019. This could further radicalise Maduro's government, which has already dismantled what was left of democratic institutions and increasingly relies on US rivals—China, Russia, Cuba and Iran.

Two elements currently act as backstops. Chevron has a sanctions waiver to operate in Venezuela and ship oil to US Gulf Coast refineries, while flights carrying deported migrants regularly land in Caracas. These align with Trump's key priorities—cheap energy, immigration control and countering China—giving an embattled Maduro hope for eventual negotiations with the US.

Caracas and Washington may indeed be heading towards negotiations soon. Presidential Envoy for Special Missions Richard Grenell recently stated: "I've been to see Nicolás Maduro. I've sat across from him, I've articulated the America First position, I understand what he wants. I believe we can still have a deal, I believe in diplomacy. I believe in avoiding war."

Yet predicting what will be on the table is difficult, as the Trump administration lacks a clear strategy. Negotiations could push for early elections with guarantees allowing Maduro to accept defeat without fearing US extradition. Washington might demand an immediate transition, though details remain to be seen. Or, as a third, dovish option, it could simply advance US interests while leaving Chavismo in place, opening Venezuela's natural resources to American businesses and taking targeted action against organised crime, from drug trafficking to the Tren de Aragua.

While influential White House figures, including Rubio, favour regime change, Trump for now appears unconvinced. Unlike his first administration, he has avoided public meetings with Venezuelan opposition leaders. He has also slashed foreign aid funding vital for civic activism in Venezuela, primarily by cutting USAID under the guise of cost savings. In previous interviews, Grenell stated that "President Trump is not looking to do regime change", but rather focused on "making the US stronger, more prosperous".

The fundamental tension remains unresolved: between those seeking to unseat Maduro and those pursuing transactional deals, between anti-narcotics rhetoric and energy interests, between tough talk on immigration and the need for Venezuelan co-operation on deportations. As military posturing escalates and negotiations loom, the question is not whether the arguably fictitious Cartel de los Soles narrative will achieve its intended effect, but rather which version of US policy will ultimately prevail—and at what cost to both Venezuelan sovereignty and regional stability.

Elías Ferrer is the founder and director of Orinoco Research, a research firm based in Venezuela for foreign investors, and editor-in-chief of Guacamaya, a Caracas-based independent digital media outlet.

Opinion

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: In Zurich, Turkey’s opposition chief was almost falling over himself to declare that power is nearly upon the CHP

It’s an interesting thought that sounds a bit too good to be true.

COMMENT: Czechia economy powering ahead, Hungary’s economy stalls

Early third-quarter GDP figures from Central Europe point to a growing divergence between the region’s two largest economies outside Poland, with Czechia accelerating its recovery while Hungary continues to struggle.

COMMENT: EU's LNG import ban won’t break Russia, but it will render the sector’s further growth fiendishly hard

The European Union’s nineteenth sanctions package against Russia marks a pivotal escalation in the bloc’s energy strategy, which will impose a comprehensive ban on Russian LNG imports beginning January 1, 2027.

Western Balkan countries become emerging players in Europe’s defence efforts

The Western Balkans could play an increasingly important role in strengthening Europe’s security architecture, says a new report from the Carnegie Europe think-tank.

_1761305900.jpg)