Water-stressed Central Asia and Afghanistan are heading for a “confrontation” over the Taliban’s building of the Qosh Tepa Canal, which will divert up to a third of the flow of the Amu Darya border river.

That’s the conclusion of journalist and researcher Galiya Ibragimova who, in a September 3 article for the Carnegie Russia and Eurasia Center, points out that, despite attempts at diplomacy, no answer has been found to the dilemma posed by the construction. The looming potential for a clash was raised by another Central Asia expert, Bruce Pannier, in an article published by bne IntelliNews as far back as August 2023.

“For now, the situation is developing through inertia toward some sort of confrontation,” writes Ibragimova.

“The ambitious irrigation project is becoming a source of growing tension in Central Asia, but none of the region’s countries have been able to come up with an alternative solution,” she says.

The Qosh Tepa Canal is scheduled for completion two to three years from now. Once finished, it will “immediately disrupt the delicate balance of water use in Central Asia”, warns Ibragimova, adding: “Previously, the Amu Darya was mainly used by Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan. Now its water will have to be shared with Afghanistan. There are already serious water shortages in Central Asian countries. Previously, they tended only to affect agriculture, but there is increasingly insufficient water for household use, and even drinking.”

Following the withdrawal of the US and allied powers from Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban, having reclaimed power, almost immediately started constructing the canal.

Almost half the planned 285 kilometres (177 miles) of the infrastructure are thought to be complete already.

A difficulty for Central Asia – used to having the Amu Darya almost entirely to itself given the decades of conflict that got in the way of Afghanistan laying claim to part of the resource with modern exploitation projects – is that any complaints about the prospect of the canal each year drawing up to 10 cubic kilometres (2.4 cubic miles) of water from the river run up against an entirely just argument.

Says Ibragimova: “No one disputes Afghanistan’s right to harness the waters of the Amu Darya. After all, about 30 percent of the river’s flow originates in the Afghan mountains, and decades of war means Afghanistan has hardly tapped this resource. The country uses just 2 cubic kilometers of water a year: eleven times less than Uzbekistan and five times less than Turkmenistan.”

In 2023, a wall section of the under-construction canal collapsed. The accident sent water gushing into surrounding land and resulted in an artificial lake of more than 30 square kilometres.

The Afghan authorities have never publicly conceded that there was such an accident, but word of events increased anxieties over out-of-date construction methods being used by the Taliban in building their megaproject.

The canal appears to lack concrete-lined walls and reinforced banks. Ibragimova says it will inevitably lose large amounts of water to sandy soil. Correcting this might be one way of raising the volume of water available for the future use of both Central Asia and Afghanistan, as might fresh attempts at persuading major growers of cotton Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to scale back their water-intensive cultivation of the commodity. Population growth in Central Asia, particularly in Uzbekistan, is adding to the water stress in the region, with urbanisation, and industrial development other difficulties as regards future water use, notes Ibragimova.

On the positive side, the canal could help rejuvenate Afghanistan’s drought-stricken agriculture sector and cut the country’s economic dependence on the illegal opium and heroin trade (in 2021, it contributed around 15% of Afghan GDP). Poppy cultivation for opium requires much less water than the growing of other crops.

Concludes Ibragimova: “Although the Taliban are not officially recognized as the legitimate rulers of Afghanistan by the Central Asian nations, there have been informal efforts to engage them in water usage discussions. But the country’s neighbors have no real leverage over the Taliban. And while the Taliban say publicly that they are open to dialogue, they also stress that the canal is a domestic issue—and that they will decide how to use their own water.”

She adds: “The only option for Afghanistan’s neighbors is to try to maintain a working relationship with the Taliban and involve them in the regional agenda.”

In May, Kazakhstan joined Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in warning that the Taliban’s construction of the canal in Afghanistan could strain fragile water security.

In October 2023, Nikolai Podguzov, chairman of the board of the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB), highlighted severe upcoming water shortages in Central Asia that would be exacerbated by the Qosh Tepa construction.

Even without the canal, Central Asia, according to the EDB, is projected to face a water deficit of five to 12 cubic kilometres annually by 2028-2029, threatening food, drinking water and energy supplies.

Features

US expands oil sanctions on Russia

US President Donald Trump imposed his first sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil companies on October 22, the state-owned Rosneft and the privately-owned Lukoil in the latest flip flop by the US president.

Draghi urges ‘pragmatic federalism’ as EU faces defeat in Ukraine and economic crises

The European Union must embrace “pragmatic federalism” to respond to mounting global and internal challenges, said former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi of Europe’s failure to face an accelerating slide into irrelevance.

US denies negotiating with China over Taiwan, as Beijing presses for reunification

Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, told reporters that the administration of Donald Trump is not contemplating any agreement that would compromise Taiwan’s status.

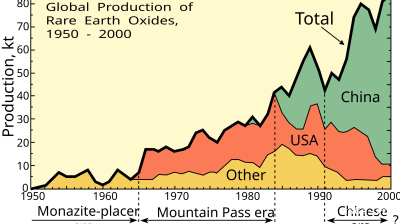

Asian economies weigh their options amid fears of over-reliance on Chinese rare-earths

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.