The foreign-calculated sums are stark. Iraq's budget deficit will more than double from 4.2% of GDP this year to 9.2% by 2026, according to the International Monetary Fund. Oil revenues, which account for over 90% of state income, are expected to tumble from $99.2bn in 2024 to just $79.2bn two years later. Meanwhile, public spending continues its inexorable climb, driven by a bloated public-sector wage bill that will devour nearly a quarter of GDP by 2026. Regional development and Iraq’s unique form of governance through the Kurds and Baghdad have already caused potential strife.

Such figures would be troubling anywhere. In Iraq, a country that has lurched from crisis to crisis for decades, they spell potential catastrophe. The IMF calculates that Iraq now needs oil at $84 a barrel to balance its books – a 55% increase from the $54 required in 2020. With Brent crude trading at around $70 and facing downward pressure from global economic jitters, that breakeven point looks increasingly fantastical and no matter how many deals the government is signing, the bills are mounting up.

For years, Iraqi governments have pledged to wean the economy off oil. The reality tells a different story. Growth in the non-oil economy has collapsed from 13.8% in 2023 to a meagre 2.5% this year, with further deceleration to just 1% expected. This contrasts sharply with the Finance Ministry's breezy forecast of 4% growth for the non-oil sector – a gap that reveals the chasm between official rhetoric and economic reality on the ground which could unravel years of hard-won gains from relative stability.

The government's diversification efforts span agriculture, industry and tourism. All have failed to gain meaningful traction. Foreign direct investment remains virtually non-existent, registering zero as a share of GDP throughout the forecast period. Such anaemic capital flows reflect deeper problems of governance, security and institutional capacity that continue to bedevil Iraq’s distant leadership.

The IMF's warnings about rising sovereign debt risks should concentrate minds in Baghdad - quickly. Government debt will jump from 47.2% of GDP in 2024-25 to 62.3% by 2026. More worrying still is the primary deficit in the non-oil budget, which will reach 59.3% of non-oil GDP this year before gradually declining to 51.8% by 2026.

These are not mere accounting entries but signals of a fundamental breakdown in fiscal discipline. The current account surplus will vanish entirely, becoming a 1.9% deficit by 2026. Foreign reserves will shrink from $100.3bn to $79.2bn over the same period – equivalent to a fall from 11.1 months of import cover to 9.6 months.

Adding to these fiscal woes is the unresolved dispute with the Kurdistan Regional Government over oil revenues and salary payments. A recent ministerial committee tasked with addressing these issues has been hamstrung by the exclusion of the oil minister and representatives from SOMO, the state oil-marketing organisation.

Basra University’s Nabil al-Marsoumi, an economist, has pointed out the obvious flaw: how can meaningful solutions be crafted when the very officials responsible for oil policy are absent from negotiations? This institutional dysfunction exemplifies the broader governance failures that have contributed to Iraq's predicament.

The IMF's prescriptions are sensible but require political will that has been conspicuously absent. Proposed measures include enhanced non-oil revenue collection, public-sector wage reform and better targeting of social programmes. Each demands the kind of difficult decisions that Iraqi politicians have consistently dodged.

Take the electricity sector, which continues to drain public coffers whilst failing to meet basic needs. Despite years of promises, billing and collection systems remain woeful. Subsidies distort market mechanisms and encourage wasteful consumption. Reform has been endlessly postponed. The social contract between state and society is fraying, and it wasn't in the best place to begin with so much distrust between power and people. Poverty levels remain stuck at 23%, unemployment is high, and basic services are patchy. Without immediate and comprehensive reforms, Iraq risks not merely fiscal crisis but potential state failure, which could then have a knock-on effect for Europe as well as the region with Syria still not in any serious functioning form currently.

Iraq's predicament is not unique among oil-dependent states, but few have squandered their advantages quite so spectacularly, maybe Iran. The country sits atop some of the world's largest proven oil reserves, yet has failed to build a sustainable economy or effective institutions despite the heft of American support for more than two decades since the Saddam Hussein era.

International partners, having invested heavily in Iraq's reconstruction and stability, have a vested interest in supporting reform efforts. But external assistance cannot substitute for the political courage and institutional capacity that meaningful change requires. The reckoning has been a long time coming and with the current US administration demonstrating it will not accept long-term high prices in the oil market, the Iraqi government must either make decisions to backtrack on its spending commitments fast.

Features

South Korea, the US come together on nuclear deals

South Korean and US companies have signed agreements to advance nuclear energy projects, aiming to meet rising data centre power demands, support AI growth, and strengthen the US nuclear fuel supply chain.

World Bank seems to be having second thoughts about Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam

Ball now in Dushanbe’s court to justify high cost.

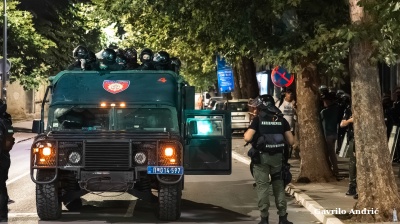

INTERVIEW: From cinema to Serbian police cell in one unlucky “take”

An Italian software engineer caught in Belgrade’s August protests recounts a night of mistaken arrest and police violence in the city’s tense political climate.

_Cropped_1756210594.jpg)

Turkey breaks ground on its section of the TRIPP rail corridor

Turkish project would help make TRIPP the go-to route for Middle Corridor freight.