The Czech and Hungarian central banks are poised to raise key interest rates this week, as Central European monetary policymakers become the first in the European Union to react to global inflationary pressures. The shift could have big implications for the region’s fragile recovery from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, as well as for the Czech koruna and the Hungarian forint.

Hungary’s central bank governor has signalled that it could raise its key policy rate when it meets on June 22, while a majority of Czech central bankers have come out in favour of a rate rise ahead of its monetary policy meeting on June 23.

Poland’s central bank (NBP) has rejected the need to raise rates – Governor Adam Glapinski saying on June 11 that it was “much too early” – but it could come under pressure to follow its neighbours when its monetary policy council next meets on July 9. It kept its reference rate at its all-time low of 0.1% on June 9.

“If regional central banks begin policy normalisation as early as in June, it would be difficult for the NBP to defend its loose policy setup,” analysts at Erste Bank commented.

Some analysts predict that Central Europe is facing a prolonged period of higher inflation that is likely to lead to a succession of interest rate hikes. “We think that the risks over the coming years are skewed to a prolonged period of much higher inflation and, subsequently, more aggressive monetary tightening,” Capital Economics said in a recent research note.

It argues that these hikes will be more significant than many expect – with the Czech central bank hiking rates by 200bps by the end of 2023. Consequently, it has revised its forecasts and is predicting stronger appreciation for the region's currencies.

If the central bank's do tighten rapidly, this would make Central Europe an outlier in Europe, with European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde saying on June 10 that there was “significant economic slack that will only be absorbed gradually”, price pressure would abate next year, and that any monetary tightening now would be “premature” and would threaten the recovery.

However, Central Europe did not have the deflation problems of Western Europe after the global financial crisis, and inflation is already nudging 5% in Hungary and Poland.

Labour markets have remained tight despite the pandemic, and wages are starting to rise rapidly again as lockdown restrictions are lifted. According to Eurostat, the region had three of the EU's five lowest jobless rates in April: 3.4% in the Czech Republic, 4.3% in Hungary and an EU-low 3.1% in Poland. In Hungary and Poland wages are already rising at or around 10%.

Central Europe looks likely to close the output gap faster than other emerging markets as it opens up after the pandemic lockdown. In the first quarter the y/y decline in GDP was 2.1% in Hungary and Czechia and 1.4% in Poland, with leading indicators predicting a rapid rise in overall growth in the region this year.

Nevertheless, according to some analysts, the global inflationary pressures – primarily in food and commodities such as fuel – are temporary, often caused by supply bottlenecks, and cannot be influenced by central bank rates. In addition, some argue the recovery remains fragile and therefore rate rises now could have damaging effects.

How serious the inflation challenge will turn out to be will depend on many variables, including on how fast pandemic restrictions are lifted as vaccination proceeds, how much pent-up demand consumers really have, and how quickly governments withdraw their support packages.

POLAND

Capital Economics says Poland’s central bank will raise rates in the third quarter of next year, but it too will be forced to raise rates aggressively from 2024 when inflation pressures becomes stronger and more persistent.

Polish headline inflation came in at 4.7% year on year in May, a pick up of 0.4 percentage points against April. Polish average gross wages in the corporate sector for companies with more than nine employees in May accelerated by a massive 10.1% y/y.

The Polish central bank and some analysts argue the inflationary pressures are just peaking now, largely due to global factors, and will fall back, and that the country’s economic recovery is at too early a stage to raise rates now.

“Inflation reached a local maximum in May … But the re-opening of the economy and the likely further rise in food prices will bring it back to the current levels at the end of the year,” the state-controlled bank PKO BP said in a recent note. “The MPC is aware of increased inflation, but in the council's opinion, it is only the result of factors beyond the control of domestic monetary policy,” PKO BP added.

However, ING predicts that headline CPI will average 4.3% y/y this year and that it “will not fall back any time soon”, remaining at 3.8% y/y next year.

HUNGARY

In Hungary, consumer prices grew 5.1% y/y in April, at the same pace as in the previous month, prompting the central bank (MNB) to indicate that the balance had shifted towards raising rates on June 22 to protect the economic recovery. "We want to eliminate persistent inflationary trends as quickly as possible", Deputy Governor Barnabas Virag said on June 9.

There is a real risk that central banks around the world will react late to inflation, Virag said, adding that the rise in core inflation is showing persistent inflationary effects. The deceleration of inflation could be protracted, and the annual inflation rate could be 4% or higher. Wages rose 8.7% in March.

Policymakers have kept the base rate on hold at 0.6% since last summer but raised the one-week deposit to 0.75% in September. Now analysts expect both the base rate and the one-week deposit rate to rise to 0.9% this week.

CZECH

In Czechia, having kept its main two-week repo rate at 0.25% since May 2020, the market has priced in almost two full hikes by the year-end, with most analysts expecting the first move on June 23.

The Czech central bank (CNB) is traditionally the most independent and hawkish of the region's central banks, and it looks set to raise rates fastest, even though Czech inflation and wage growth is less dramatic than its neighbours. The CNB's own quarterly staff forecast update from May pencilled around three interest rate hikes by year-end.

Czech inflation eased to 2.9% in annual terms in May after a jump to 3.1% in April, but this is still right on the edge of the bank’s target of 2%, with a 1% tolerance band.

The economy appears to be starting to recover, after a decline of 2.1% y/y in the first quarter. Tomas Holub of the central bank says he is now expecting growth this year to average 2.5% or more, which is lessening the risk of raising rates.

In particular, the labour market appears remarkably unscathed, partly because of government measures to support companies and workers. Unemployment remains low, the country’s acute shortage of labour is reappearing and wages are starting to rise again, with 3.2% growth in the first quarter.

For the central bank, therefore, it is important to re-establish inflationary expectations particulary as the government is in no hurry to rein back pandemic spending ahead of the general election in October.

“According to them [CNB board members], the main reason for tightening monetary policy so soon is inflation, which has been above the 2% target for more than two years,” Martin Gurtler, chief economist of Komercni Banka, told kurzy.cz. “The June rate hike, which we expect to be in the 25bp range, should thus play a mainly signalling role, indicating the CNB's determination to fight higher inflation. However, the repo rate should not exceed 1% by the end of the year.”

Features

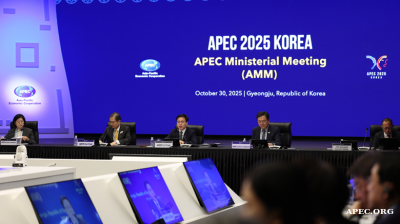

Global leaders gather in Gyeongju to shape APEC cooperation

Global leaders are arriving in Gyeongju, the cultural hub of North Gyeongsang Province, as South Korea hosts the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. Delegates from 21 member economies are expected to discuss trade, technology and security.

Project Matador marks new South Korea-US nuclear collaboration

Fermi America, a private energy developer in the United States, is moving ahead with what could become one of the most significant privately financed clean energy projects globally.

CEE needs a new growth model as FDI plunges

wiiw economist Richard Grieveson says the CEE region’s long-standing model of attracting FDI through low labour costs no longer works.

KSE: Ukraine is facing a $53bn budget shortfall, but economy is stable for now

Ukraine is in urgent need of additional financing from partners as the continuation of the war drives up defence spending and reconstruction needs, jeopardizes budget financing, weighs on the balance of payments, and slows economic growth.