Armenia is stepping up efforts to reduce its reliance on Russia, deepening ties with Europe and the United States after Moscow failed to protect it in recent conflicts with Azerbaijan, according to a new analysis by Dutch think-tank Clingendael.

But Yerevan’s path to independence is constrained by geography, security threats and deep economic ties to Moscow, forcing the small South Caucasus nation to walk what the report calls a “tightrope balancing act”.

“While Armenia’s disappointment in Russia is deepfelt and the effort to distance from it genuine, the long-standing dependencies on Russia in terms of energy, economics and trade, coupled with Armenia’s geographic isolation, make it difficult for Yerevan to make zero-sum geopolitical ‘either-or’ choices,” wrote the report’s author Marina Ohanjanyan, a senior research fellow at Clingendael.

The report says Armenia’s drift began after its 2018 “Velvet Revolution”, which ushered in a government focused on democratic reforms and anti-corruption measures that “clashed with the Russian model”. Frustrations boiled over after Russia’s failure to help Armenia during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and the 2021-22 Azerbaijani incursions into Armenian territory.

The 2023 fall of Nagorno-Karabakh further shook confidence in Moscow as a security guarantor, with the word “betrayal” now common in Armenian public discourse, the report says.

In a major shift, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced in February 2024 that Armenia had frozen its membership in the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), halting participation in military exercises and financial contributions.

“Once seen as the primary ally and security guarantor, Russia is now increasingly viewed in Armenia as a threat and a constraint on Armenian sovereignty,” Ohanjanyan wrote.

Armenia has moved to strengthen ties with the EU and the US, signing a Charter on Strategic Partnership with Washington in January 2025 covering economic and security cooperation, and expressing interest in eventual EU membership.

Yet the report cautions that “any idea of completely replacing Russia or effectively ignoring its presence in the region is considered utterly unrealistic and potentially dangerous.”

The study notes that Russia’s military alliance with Armenia “on paper still remains”, but its reliability has collapsed, prompting Yerevan to diversify arms imports away from Moscow. India and France have emerged as Armenia’s main weapons suppliers.

Prime Minister Pashinyan has accused Moscow of waging a “hybrid war” against Armenia, citing propaganda and cyberattacks targeting the government and civil society.

“Russia’s leverage as a security provider has evaporated,” the report says, but warns that Moscow could retaliate if Armenia crosses red lines, such as demanding the withdrawal of Russian troops or formally quitting the CSTO.

Despite political tensions, Armenia’s trade with Russia has surged since Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, partly due to re-exports of goods banned in Western markets.

“Despite Yerevan’s intent to reduce dependence on Russia, economy and energy remain the most challenging areas, due to geographic and geopolitical limitations,” Ohanjanyan noted, adding that Russian fossil fuels still dominate Armenia’s energy supply.

Plans to diversify Armenia’s energy mix, including boosting renewables, “will take time and a major effort”.

Clingendael’s report also points to a profound change in societal attitudes toward Russia, with public perceptions shifting “from trusted ally to a (potential) threat.” Moscow’s once-strong soft power in Armenia has weakened, and the Kremlin lacks credible political allies ahead of Armenia’s 2026 parliamentary elections.

Nevertheless, the report warns that Russia may attempt to influence those elections through “propaganda, disinformation or other hybrid means.”

The report argues the EU can help Yerevan reduce its reliance on Moscow by deepening cooperation in trade, energy, and governance. However, Armenia’s officials are keen to avoid provoking Russia while seeking diversification.

“Changes in Armenia’s approach to its relationship with Russia are based not on exchanging one global power (Russia) for another (the West), but rather on a diversification policy,” Ohanjanyan concluded, noting that while the West can help, Armenia’s geographic isolation and security threats from Azerbaijan complicate its options.

For now, Armenia’s shift Westward is real but cautious, reflecting a country seeking new partners while watching over its shoulder as it redefines ties with its old patron.

Opinion

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.

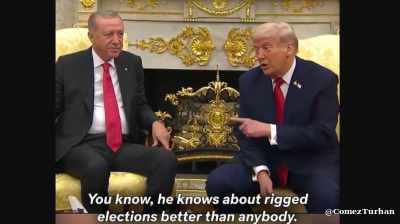

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Consumed by the Donald Trump Gaza Show? You’d do well to remember the Erdogan Episode

Nature of Turkey-US relations has become transparent under an American president who doesn’t deign to care what people think.

COMMENT: ANO’s election win to see looser Czech fiscal policy, firmer monetary stance

The victory of the populist, eurosceptic ANO party in Czechia’s parliamentary election on October 6 will likely usher in a looser fiscal stance that supports growth and reinforces the Czech National Bank’s recent hawkish shift.