Most post-communist EU member states are struggling to address corruption effectively, said international watchdog Transparency International as it released its latest Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) on January 23.

The Western Europe and EU region is the best performing region worldwide, with its member countries earning an average score of 66 out of 100 on the CPI, which uses a scale of zero to 100, where zero is highly corrupt and 100 is very clean.

However, with some exceptions, the newer EU member states in the eastern part of the bloc perform less well than their peers to the west on the index that ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption in 2019.

Of the 11 countries in the region only one, Estonia, had a score higher than the EU average.

Many countries in the region — Croatia, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Hungary, Poland and Romania — saw their scores worsen compared to the 2018 ranking.

Bulgaria remained the most corrupt country in the EU, lagging behind countries such as Hungary and Poland. In the 2019 Corruption Perception Index Bulgaria ranked 74th along with Jamaica and Tunisia with a score of 43 – one point more than in the previous ranking but still significantly below the EU’s average of 66.

“Being below the average value of the index [of 50 points] means that there are systematic or deep problems with the corruption. In the past seven years we sustainably remain on this level. There is no significant progress in the fight against corruption,” Kalin Slavov, executive director of Transparency International for Bulgaria, said at a press conference as quoted by Dnevnik news outlet.

Bulgaria has seen the eruption of numerous corruption scandals during the last year, culminating in recent weeks with the arrest of the environment minister, Neno Dimov, who became the first sitting minister ever to be arrested in the country.

He has been charged over suspicions that he enabled the illegal siphoning of water from the Studena reservoir, which cut off supplies to the industrial town of Pernik, affecting over 100,000 people. The opposition also claim illegal waste imports were sent to Bulgaria by the Italian mafia to be burnt in local power plants.

The environment scandal came on top of several other scandals embroiling members of Prime Minister Boyko Borissov’s government, as well as a public outcry over the appointment of the much criticised Ivan Geshev as chief prosecutor, one of the most powerful positions in Bulgaria.

In other Central and Southeast European countries, Transparency International criticised efforts at judicial “reform” that have weakened judicial independence.

“Several countries, including Hungary, Poland and Romania, have taken steps to undermine judicial independence, which weakens their ability to prosecute cases of high-level corruption,” says the report.

This has brought both Hungary and Poland into direct conflict with Brussels. In the latest development, Poland’s lower house of parliament adopted the so-called “muzzle law” that makes it possible to discipline judges if they speak out against the government in December.

Thousands of people led by Polish judges and their colleagues from across Europe marched in central Warsaw on January 11 in protest against plans of the Law and Justice (PiS) government to curb the independence of the judiciary via the law. As was the case with several other attempts by PiS to introduce changes to the Polish judiciary, the EU and other institutions lambasted the new regulation as threatening the rule of law.

Power in one man’s hands

Over the last eight years Hungary has seen its ranking deteriorate from 55 points to the second-lowest among EU members, tied with Romania and ahead of only Bulgaria.

In the past decade corruption has become centralised and institutionalised, a hybrid regime and crony capitalism formed, said TI Hungary's managing director Peter Jozsef Martin said after the report. The government takes over assets from private certain groups by legal means and hands it over to certain groups, well alligned with the government, which often is against the law. This allowed the government to pump money to the new politically-connected elite largely.

Nowhere in the EU does a government, a state and ultimately one man, the prime minister, have this much power, according to the report.

Transparency's report highlights a list of corruptions schemes from the previous years, such as the golden Visa scheme for residents and the sport donation system through tax exemption. The former owners of Elios, including the son-in-law of PM Viktor Orban escaped prosecution by Hungarian authorities despite the EU's anti-fraud office OLAF revealed severe irregularities and traces of organised fraud linked to the company, which won EU money to modernise street lighting. The government implicitly acknowledges fault in the Elios case, as it chose not to submit invoices to Brussels for reimbursements of EU funds related to a high-profile corruption case.

The report concludes that the use of EU money in Hungary carries a number of systemic corruption risks. Public procurements accounted for 6.5% of the GDP in recent years and EU tenders accounted for half of that figure.

Lorinc Meszaros seen by many as the proxy to Viktor Orban has become Hungary's most powerful oligarch and wealthiest businessman. The report estimates that while between 2011 and 2016 the then-mayor of the prime minister's home village Felcsut won less than 1% of all public procurement money, by 2017 it had jumped to 5.4% and accounted for 3.7% in 2018.

Meszaros' companies won 46 EU public procurements of the 47 in which they ran in 2017-2018. They took a whopping 20% of all EU funds, or HUF426bn (€1.3bn) during the period.

Deepening state capture

Popular anti-corruption movements are emerging in response in a number of countries in the region. The Czech Republic was one country that saw tens of thousands of people take to the streets last year to protest against official corruption.

The country slipped six spots on the index compared to last year to 44th place. According to TI Czech Republic, the drop reflects the near-zero development of anti-corruption legislation in the country and the ever-deepening state capture.

“In the Czech Republic, recent scandals involving the prime minister and his efforts to obtain public money through EU subsidies for his company highlight a startling lack of political integrity. The scandals also point to an insufficient level of transparency in political campaign financing,” said Transparency International’s report.

“Issues of conflict of interest, abuse of state resources for electoral purposes, insufficient disclosure of political party and campaign financing, and a lack of media independence are prevalent and should take priority both for national governments and the EU.”

“The Czech Republic has been stagnating, or even worsening in reducing corruption, openness and the quality of the public sector. Without a functioning state, high-quality institutions and consistent justice, we will never catch up with the world leaders. The government cannot endlessly paint the state of the public administration pink,” commented TI Czech Republic director David Ondracka.

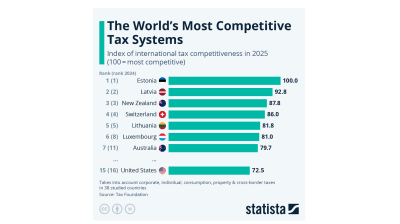

Estonia was the top ranked country from the region, having risen 10 places since last year’s index was released, in 18th place overall.

“A comprehensive legislative framework, independent institutions and effective online tools make it possible to reduce petty corruption and make political party financing open and transparent [in Estonia],” says the report. “There is a need, however, to legally define and regulate lobbying to prevent and detect undue influence on policy-making.”

Estonia’s impressive score was assigned despite revelations of money laundering on a massive scale via the local branch of Danske Bank.

“Although private sector corruption is not captured on the CPI, recent money laundering scandals involving the Estonian branch of Danske Bank demonstrate a greater need for integrity and accountability in the banking and business sectors. The scandal also highlights a need for better and stronger EU-wide anti-money laundering supervision,” said Transparency International.

Other countries that performed well on this year’s index were Lithuania and Slovenia (tied in 35th place).

News

Category 5 hurricane Melissa bears down on Jamaica with Haiti and Cuba in storm's path

A catastrophic Category 5 hurricane was bearing down on Jamaica on Monday, October 27 afternoon with sustained winds of up to 282kph (175mph), threatening to become the strongest storm the Caribbean island has ever experienced.

.jpg)

US senator tells Maduro "head to Russia or China" as warships close in on Venezuela

A senior US Republican senator has warned that Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro's time in power is running out and suggested he leave the country, as military tensions in the Caribbean continue to escalate.

Milei celebrates resounding victory in Argentina's midterm elections

Argentine President Javier Milei scored a major win for his La Libertad Avanza (LLA) party in Argentina's October 26 midterm legislative elections, as the party obtained approximately 40.84% of the nationwide vote with 99.14% of the votes counted.

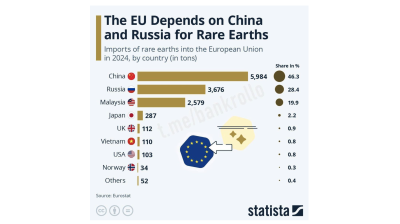

Zelenskiy accuses China of aiding Russia’s war effort through industrial and military support

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy accused China of materially supporting Russia’s military-industrial complex, providing key technologies and resources that have enabled Moscow to sustain and scale its war effort against Ukraine.