Deathonomics: Russia’s war in Ukraine creates a new kind of middle class

Some economists have dubbed it “deathonomics”. Russia’s heavy military spending is transforming the country’s income profile out of all recognition and has lifted millions out of poverty. It has created a new kind of middle class. The only problem with the transformation is you might be dead at the end of it.

The war in Ukraine has created a new kind of middle class in Russia out of the country’s poorest inhabitants. And it is flourishing. Savings are up. Families are leaving run down villages and buying nice apartments in the regional capital and wages are multiples of the national average. The problem is to tap into this prosperity you have to go and fight in the war in Ukraine where you run a high chance of being killed.

The extraordinarily high sign-up payments regional governments are shelling out to persuade Russian men to sign up to meet their quotas and the even larger payments made to the families of those killed in action are feeding to the far flung regions in Russia’s impoverished hinterland. These towns and villages largely missed out on the economic boom that lifted the country after Russian President Vladimir Putin took over in 2000 and outdoor toilets are common and a kitchen garden to grow potatoes and fruit are essential.

Russia's economy has enjoyed a military Keynesianism boost following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 as the state poured billions of dollars into military spending. Instead of collapsing under the weight of the most extreme sanctions regime ever imposed on a country, after an initial modest dip in 2022, Russia’s economy became the fastest growing major economy in the next two years expanding by 4.3% in both years.

The chronic labour crisis caused by military recruitment pushed up wages to new highs and unemployment down to all-time lows driving up real incomes for everyone left at home. Until recently, Putin successfully shielded the bulk of the population from the effects of the war, except for growing inflation, and bne IntelliNews interlocutors in Moscow report that many Russians say the last three years has been amongst the most pleasant and prosperous years since the Soviet Union fell in 1991.

As bne IntelliNews reported, the rising wages and full employment has created a new war middle class across society in general, but it has also eroded some of high income equality that plagued Russia before hostilities broke out. Russia’s poorest regions have been the biggest winners from the conflict as the government has recruited the most soldiers from these places. Separately, a survey of regional retail banking account deposits, conducted by the Bank of Finland Institute for Emerging Economies (BOFIT) also showed that deposits in the poorest regions have soared in the last few years as soldiers send their wages home, or the family receives very large payments if they are killed or wounded.

The sums on offer are mindbogglingly large by local standards. A Siberian bus driver can expect to double or quadruple his pay. Contract soldiers now earn up to $90,000 a year, compared with average local wages of $8,000. Defence factories run around the clock on three shifts a day, while wages in metalworking have surged by 78 per cent since 2021.

Tymofiy Mylovanov, president of the Kyiv School of Economics, argued that “Putin turned idle workers and jobless men into cannon fodder and channelled their wages and death payouts into local economies.” Families once living on the margins “now buy apartments in regional cities,” he wrote on X.

Compensation for casualties further deepens the effect. An estimated million men have been killed or wounded in the war so far. Families of fallen soldiers receive up to $120,000 in payouts, alongside gifts from local officials “— anything from fridges to meat grinders.” For many households in Tuva, Altai and the North Caucasus, Mylovanov noted, “war deaths bring more money than years of regular work.”

Previously depressed industrial towns that never recovered after the collapse of the Soviet Union are experiencing a boom. Munitions and uniform factories hire thousands, while new cafés, gyms and salons open their doors. Families supported by “war money” are also fuelling domestic tourism, which was up by 8% this year and tours to Europe up by 30-50%, according to Russia’s tourism union.

The Kremlin is reinforcing the trend by reserving 50,000 university places in 2025 for soldiers and their children, bypassing competition. Nearly 15,000 enrolled in 2024, up from 8,000 a year earlier.

The balmy economic conditions Russians have enjoyed for the last two years may be coming to an end soon as Russia’s economic problems are getting worse after the regulator decided to artificially slow growth to take the edge off sticky inflation and so bring down sky high interest rates.

Russia’s economy contracted in the first quarter of this year in real terms and narrowly missed a technical recession in the first half of this year. But even if growth falls to nothing, the Kremlin will still pay those extraordinary wages as it digs into its vast reserves of capital, built up over a decade in the run up to the war. Putin has been planning for this conflict since 2012 when he switched economic policy from investment to modernising the military and ordered the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) to accumulate cash and gold.

The massive largess that has been lavished on the population in the form of extraordinarily high wages may come back to bite Putin should the war in Ukraine end. Demobilised soldiers returning home to their impoverished regions and low-paying jobs could be socially disruptive.

“Peace would undo it,” Mylovanov warned. Hundreds of thousands of veterans would return to low-wage towns and rapidly exhaust their savings. The result, he suggested, could be a “social disaster like Germany in the 1920s, when embittered veterans destabilised politics.”

Analysts say that the Kremlin will keep military spending high in the first years after the war as Russia needs to rebuild its military and restock after burning through its Soviet-era stockpile of materiel, to be able to defend itself against a possible Nato attack. But, Putin may have no choice other than to continue to invest into unproductive military hardware, as cutting wages back could quickly lead to protests by the newly employed veterans that served in Ukraine but have a bleak future in the run down regions of Russia. And economists are already warning of the dangers of recession or even stagflation if Russia goes down that road.

Features

Turkmenistan’s TAPI gas pipeline takes off

Turkmenistan's 1,800km TAPI gas pipeline breaks ground after 30 years with first 14km completed into Afghanistan, aiming to deliver 33bcm annually to Pakistan and India by 2027 despite geopolitical hurdles.

Looking back: Prabowo’s first year of populism, growth, and the pursuit of sovereignty

His administration, which began with a promise of pragmatic reform and continuity, has in recent months leaned heavily on populist and interventionist economic policies.

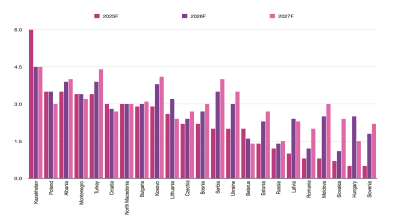

Emerging Europe’s growth holds up but risks loom, says wiiw

Fiscal fragility, weakening industrial demand from Germany, and the prolonged fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine threaten to undermine growth momentum in parts of the region.

The man who sank Iran's Ayandeh Bank

Ali Ansari built an empire from steel pipes to Iran's largest shopping centre before his bank collapsed with $503mn in losses, operating what regulators described as a Ponzi scheme that poisoned Iran's banking sector.