The reconstruction of Ukraine – which will be discussed at a key conference in London on June 21-22 – is often linked to the possibility of using frozen Russian private and public assets.

This idea has been promoted by Western politicians, lawyers and economists, as well as Ukrainian leaders. But it could have serious drawbacks, and the West could achieve better results by using its financial muscle in a smart way.

The pressure for using the Russian assets is of course understandable. Since it will be difficult under realistic scenarios to expect a Putin-led Russia to make prompt reparation payments to Ukraine, it might appear justified to use Russian foreign assets. After all, Russia’s war damage in Ukraine is now in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Handily, the business model of the elites in Putin's Russia has long been to accumulate substantial assets abroad. This was also partly the strategy of Russian decision makers for handling Russia's excessive foreign exchange reserve holdings.

Moreover, Russia is and will remain a wealthier country than Ukraine for a long time to come. Currently, Russia's GDP per capita is about $14,000, while Ukraine's is about $4,000. Russia's bumper 2022 current account surplus of just over $200 billion has already rebuilt almost all of the frozen foreign exchange reserves. Currently, the reserves are estimated at about $580 billion, only slightly below its 2021 peak ($631 billion). The actual reserve position is sufficient to cover more than 20 months of imports (in a hypothetical scenario, without any further foreign currency inflows).

(Foreign currency reserves, $bn)

Confiscating some $200bn-$300bn of frozen foreign exchange reserves would therefore not put Russia into a precarious situation and turn it into a second Weimar Republic.

Confiscated funds do not necessarily even have to flow directly to Ukraine but could be used for Western aid, acting as a "tranquilizer pill" for taxpayers already becoming impatient with their financial support for Ukraine.

But beware: There are also spillover effects here. A seizure of state assets (foreign exchange reserves) by the West (USA, Europe, G7) could damage confidence in the legal systems in Western countries.

There are arguments that, with appropriate legal changes, access to foreign exchange reserves could be made possible. However, it cannot be ruled out that in our Western legal systems this step will not be classified as legally compliant by constitutional courts or international case law ex-post. And nothing would be more embarrassing for the West if Russia were to be proven right in a lawsuit against a confiscation of its foreign exchange reserves.

Furthermore, it is not only a matter of confidence in the legal systems, but also of confidence in the leading Western currencies, financial centres and reserve assets. It is important not to forget that the West still has a very strong lever here with the key role of the USD and EUR and corresponding liquid sovereign debt markets. How difficult it is (currently still) to circumvent the USD and EUR or assets denominated in these currencies in terms of liquid, sovereign reserve positions that can be used on the financial market is shown by the strong gold purchases by central banks. And gold is rather a suboptimal substitute for classical (interest-bearing) reserve assets.

Proponents of reserve confiscation can, of course, argue that this threat of confiscation would only worry a "rogue state" such as Russia. However, the slippery slope argument also applies. If substantial foreign exchange reserve positions of a large G-20 country were to be seized, then this measure could possibly be used later, even in the case of lesser dramatic frictions of a country with the Western world.

China in particular could use the "confiscation moment" to strengthen the role of its own national currency internationally as a reserve currency. At present, the Chinese currency still lacks a few things to achieve the status of a global reserve currency; concerns about "politicisation" and possibly a lack of rule of law could be decisive factors here. If assets even in USD and EUR are no longer safe under the rule of law, then yuan assets may be more acceptable to some players.

It may also be appropriate to take a broader ethical and moral view here. First, Russia's excessive foreign exchange reserves were accumulated at the expense of Russia's population or were part of an economic policy geared to austerity rather than development. In this respect, one can at least think about a return (of part) to a future Russia without Putin. Second, many other states have also suffered from Russia's aggressive foreign policy policies – albeit not as massively as Ukraine. To that extent, there might also be other valid claims to consider here.

It may also make sense for Europe to take its own position on these issues. In the long run, the euro will have to struggle more than the U.S. dollar to maintain and/or increase its current global role as a major (reserve) currency. In this respect, it may be rational to oppose a rash use of Russian foreign exchange reserves (in EUR and/or frozen in the euro area or the EU) – no matter how the U.S. acts from its position of perceived strength when it comes to global financial markets.

It might seem an easier option to distinguish between public and private frozen Russian assets. Confiscating Russian private assets would also, to a certain extent, bring about a necessary process of coming to terms with the West’s culpability. For too long, the West has turned a blind eye to dubious money and asset inflows from Russia.

Currently, there are about $30bn-$50bn of Russian private assets frozen in Western jurisdictions; according to estimates, there could be as much as $100bn. Should private assets ("oligarch money"), in a constitutional process, be clearly linked to criminal activities, the sanctioned Russian war machine and/or sanctions evasion, then a seizure and use of these sums for the reconstruction of Ukraine seems plausible.

However, the sums to be estimated here will certainly not bring in substantial funds. In addition, perhaps public authorities will lose court cases, because sophisticated shell structures and/or transfers to other persons/entities may have occurred. In this respect, it will be difficult to count on a fixed amount (though a lost lawsuit would probably cause less damage to the West’s reputation than a successful lawsuit against the confiscation of foreign currency reserves).

Financial engineering

Rather than confiscating Russia’s frozen foreign exchange reserves, a better policy is to use them as leverage, especially since hardly anyone assumes that Russia will have access to the reserves quickly and/or will need them. Accruing interest income could be used to cover part of the costs of Ukraine's reconstruction.

Moreover, an unfreezing and also a conceivable return of Russia to Western capital markets could be linked to Russia reaching agreement with Ukraine on reparations. Here, it is conceivable that the West would gradually withdraw its oil price cap and that Russia would have to make parts of its energy export revenues available to Ukraine in return (roughly at least in the amount of Russia's frozen foreign exchange reserves).

Such a mechanism could fit in well with the UN resolution of November 2022, which called for Russian compensation or reparations payments, and urged the establishment of a corresponding mechanism. A departure from the oil price cap – if the environmental conditions are suitable – can make sense. Otherwise, some geo-economic rivals benefit from very cheap energy.

Europe could still send clear signals that it will approach the reconstruction of Ukraine on a large scale and with commitment. Although the reconstruction of Ukraine is certainly a global and international undertaking, it can be assumed that Europe and the EU in particular will have to bear the bulk of the financial reconstruction costs in the long term. Based on the experience of international reconstruction programmes, Europe is expected to contribute at least 60-70%.

For example, Europe could provide Ukraine with funds raised on the capital market in the long term or lend them, only setting very long repayment periods, for example, in the range of 20 or 30 years.

Such "financial engineering" could make sense. In the long term, Ukraine can expect interest or refinancing costs of at least 5-9% (if Ukraine is in a better macro-financial position in a few years) over the cycle on the international capital market, while respective values for the EU could be 2-3%. Thus, in this respect, such a transfer of funds would be economically very rational.

Moreover, in the course of a reconstruction process, Ukraine should have sufficient growth potential as an emerging market, which should favour the repayment of substantial sums at low interest costs (with interest rates like a developed country or the EU) over a long period of time. By doing this, the EU would show confidence in the reconstruction process or would itself be invested. An EU guarantee for certain parts of Ukraine's capital market financing would also be conceivable.

Furthermore, the EU itself could again raise funds on capital markets in order to fund its contribution to the "generational task" of reconstructing Ukraine. And such a further earmarked borrowing (as for the COVID-19 reconstruction, Next Generation EU) could take some wind out of the sails of efforts to simply strive for a general common debt financing within Europe.

The considerations outlined here before should in no way be understood as "appeasement" of Russia. Rather, it is about actively dealing with aspects of geo-economic competition, our own positions of strength of the West (in the global financial system) and bearing in mind the current China-Russia axis.

In this respect, it could be rational not to undermine the Western strong global position in reserve assets or "safe assets" with a hasty recourse to Russian foreign exchange reserves. And if one refrains from this idea, then one opens the space for other sources of financing.

Gunter Deuber is chief economist of Raiffeisen Bank International in Vienna. This article is written in a personal capacity and only reflects the opinion of the author.

Opinion

COMMENT: Czechia economy powering ahead, Hungary’s economy stalls

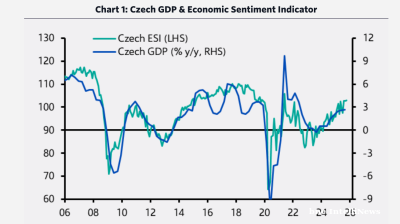

Early third-quarter GDP figures from Central Europe point to a growing divergence between the region’s two largest economies outside Poland, with Czechia accelerating its recovery while Hungary continues to struggle.

COMMENT: EU's LNG import ban won’t break Russia, but it will render the sector’s further growth fiendishly hard

The European Union’s nineteenth sanctions package against Russia marks a pivotal escalation in the bloc’s energy strategy, which will impose a comprehensive ban on Russian LNG imports beginning January 1, 2027.

Western Balkan countries become emerging players in Europe’s defence efforts

The Western Balkans could play an increasingly important role in strengthening Europe’s security architecture, says a new report from the Carnegie Europe think-tank.

COMMENT: Sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil are symbolic and won’t stop its oil exports

The Trump administration’s sanctions on Russian oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil, announced on October 22, may appear decisive at first glance, but they are not going to make a material difference to Russia’s export of oil, says Sergey Vakulenko.