Protests erupted across Tanzania on October 29, voting day in a general election widely seen as non-competitive, with President Samia Suluhu Hassan facing no major challenger after opposition figures were barred, detained, or withdrew in protest over electoral conditions.

Demonstrators clashed with security forces in Dar es Salaam, setting a bus and a gas station ablaze, prompting authorities to impose a curfew from 6 p.m., the Associated Press reports. The military was deployed in Dodoma, Zanzibar, and the commercial capital, while internet service was disrupted nationwide.

Hundreds demonstrated in the Kimara and Ubungo districts, with unrest also reported in Magomeni, Kinondoni and Tandale. Polling stations were vandalised in Arusha and Mbeya outside the capital.

Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner Albert Chalamila said security agencies were prepared to deal with any “disruptors of peace.” The U.S. Embassy issued a security alert, warning of “country-wide” protests in Tanzania.

In the lead-up to the general election, opposition figures, activists, and government critics reported surveillance, intimidation and arbitrary detentions, while local civil society organisations said political rallies and dissent were increasingly restricted.

Tanzania’s main opposition party, Chadema, said it would boycott the presidential and parliamentary elections unless the government implemented what it calls "fundamental electoral reforms".

Preliminary results are expected on October 30, with the National Electoral Commission due to announce the final outcome within seven days.

Turnout was low, observers reported, particularly among young voters. University student James Matonya told the AP he did not vote because the election was a “one-horse race.”

Hassan assumed the presidency in 2021 following the death of John Magufuli. She is facing 16 candidates from smaller opposition parties. Tanzania has more than 37mn registered voters, a 26% increase from 2020.

Chadema’s disqualification in the contest came amid broader political tensions, including a treason charge brought in April against party leader Tundu Lissu, who was blocked from contesting. Another prominent opposition figure, Luhaga Mpina of ACT-Wazalendo, was also barred from seeking the presidency.

Early voting in Zanzibar by electoral and security officials was criticised by the ACT-Wazalendo party for alleged irregularities, including impersonation and the barring of party representatives.

While Tanzania is a multiparty democracy, a version of Hassan's CCM – whose name translates as the Party of the Revolution – has been in power since the East African country won independence from Britain in 1961.

Rights and pro-democracy groups, such as Amnesty International and Freedom House, say that under Hassan, there has been a narrowing of political space, although her government maintains that legal processes are being followed.

David Omojomolo, Africa Economist at Capital Economics, wrote in a note to clients ahead of the vote Tanzania’s presidential election is likely to result in a win for incumbent Samia Suluhu Hassan and ongoing investments into infrastructure and the extractives sector will support strong GDP growth in the coming years.

“The key risk is post-election unrest – and a government backlash – which could call into question the concessional financing that Tanzania is reliant upon,” he said, adding that a key economic risk is how international donors like the IMF and World Bank perceive the government’s response to any unrest.

“The World Bank, for example, has in the past suspended disbursements – just last year an infrastructure project was halted due to complaints of excessive government force directed towards communities affected by a funded project.”

“The multilaterals are critical given how reliant Tanzania is on concessional financing. The IMF estimates that concessional financing is needed to cover around half of Tanzania’s gross financing needs (total fiscal financing needs), which are equal to around 6% of GDP per annum, over the coming years.

“A scenario where the IMF or World Bank were to be more reluctant to lend further to Tanzania would be particularly damaging given open questions as to whether Tanzania could successfully access international capital markets in its place – it has struggled to issue a Eurobond for some years, for example.”

News

US strikes on drug vessels kill 14 in deadliest day of Trump's narcotics campaign

The US military killed 14 people in strikes on four vessels allegedly transporting narcotics in the eastern Pacific Ocean, marking the deadliest single day since President Donald Trump began his controversial campaign against drug trafficking.

Russia withdraws from Cold War plutonium disposal pact with US

Russian President Vladimir Putin has formally withdrawn from a key arms control agreement with the United States governing the disposal of weapons-grade plutonium, as the few remaining nuclear security accords between the two powers vanish.

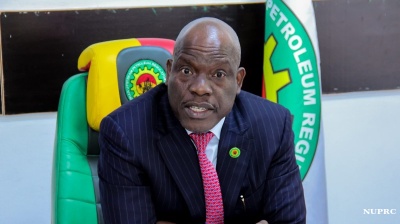

Nigeria’s NUPRC holds exploratory talks with Bank of America on upstream financing

Nigeria's upstream regulator, NUPRC, has held exploratory talks with Bank of America as the country looks to attract new capital and revive crude output, after falling short of its OPEC+ quota.

European diplomacy should have stopped war, Orban tells Italian broadcaster

The job of European diplomacy would have been stopping the war in Ukraine, but Brussels has become "irrelevant" by deciding not to negotiate, Prime Minister Viktor Orban told an Italian TV channel on October 28.