The liberalisation of Kosovo’s electricity market, formally launched in mid-2025, was meant to bring the country closer to European Union standards and foster competition in the energy sector.

Instead, the reform has become a heavy burden for businesses, prompting widespread criticism from the Kosovo Chamber of Commerce and Industry and other associations.

Disconnections of hundreds of companies this summer, following their failure to secure supply contracts on the open market, have highlighted both the fragility of the process and the absence of meaningful dialogue between regulators, suppliers and the private sector.

From regulation to liberalisation

In March 2025, Kosovo’s Energy Regulatory Office (ERO) announced that, as of June 1, around 1,300 companies would be required to leave the regulated tariff system and sign contracts with licensed suppliers under the newly liberalised framework. The decision, ERO said, was in line with EU energy directives and would gradually open the market to competition, ensuring fairer pricing and long-term efficiency.

But the announcement came without consultations, detailed analysis or gradual transition, according to business associations. Several firms challenged the measure in court, yet in August, the Second Instance Chamber of the Commercial Court upheld ERO’s decision, clearing the way for its implementation.

By mid-August the situation escalated. The Kosovo Electricity Distribution Company (KEDS) began disconnecting around 450 businesses that had not signed supply contracts. Some 1,400 meters were identified, with about 600 cut remotely and the rest disconnected on site. KEDS insisted it was legally bound to enforce ERO’s rulings, stressing that non-compliance amounted to a breach of the electricity law.

The ERO has pursued market liberalisation since 2017, though progress was temporarily halted by the pandemic and the subsequent energy crisis, which undermined supply security and market stability.

“Businesses treated like thieves”

The Kosovo Chamber of Trade and Industry (CTIK) said that liberalisation in its current form is undermining production, investment and employment.

“Two companies have already halted production entirely, another is considering terminating contracts with farmers, while several others have warned of job cuts. Investment plans have been cancelled, and some companies are even contemplating leaving Kosovo. In this situation, many businesses are facing a major struggle: how to cope with the high costs brought by energy market liberalisation,” Kushtrim Ahmeti, executive director of CTIK, told bne IntelliNews.

He also criticised the way disconnections were carried out. “A large number of our members have faced forced disconnections from electricity, despite the fact that they are still awaiting a response from the first instance of the Commercial Court. The disconnections were carried out in the presence of numerous police forces, leaving a bitter impression as if the action were being taken against electricity thieves rather than businesses that have regularly paid their bills. Moreover, we have been informed of cases where even businesses holding supply contracts with licensed companies under the liberalised energy market were disconnected,” Ahmeti added.

Transparency concerns

Beyond immediate disruptions, the chamber has pointed to structural flaws in the way ERO implemented liberalisation.

“Although in normal terms liberalisation should have served as a positive foundation, in our case unfortunately it has done the opposite. We have never been against the liberalisation of the energy market itself, but we have opposed the form chosen by the Energy Regulatory Office (ERO) to implement it. The entire process has been accompanied by numerous irregularities and a complete lack of transparency,” Ahmeti said.

According to the association, ERO introduced two conditions for inclusion in the liberalised market: companies must have more than 50 employees and an annual turnover of up to €10mn. These thresholds meant that certain startups and small firms entered the liberalised market despite limited financial capacity, while some high-consumption businesses were excluded because they did not meet the headcount criterion.

“ERO based its decision on the number of employees in 2024, but not in 2025, when many companies had fewer employees due to economic difficulties and the outflow of professional staff,” Ahmeti noted.

Another issue is the licensing of new suppliers. “The vast majority of companies were licensed in the final week before liberalisation began. We have no information about their experience in this field, and some of them have connections with key figures in the government of Kosovo,” he warned.

Delays requested

Ahmeti said that the chamber has repeatedly sought to delay the process. “As the Chamber of Trade and Industry of Kosovo, we have made significant efforts to request that the process be postponed for at least one year, during which time public consultations should have begun so the process could move forward gradually. The European Union itself reached the same conclusion, yet ERO and the institutions showed no willingness to find a solution.”

Although courts did not suspend liberalisation, proceedings revealed “a large number of violations, for which we believe ERO officials must be held accountable,” he argued.

The chamber has approached Kosovo’s presidency, government, the ERO and state-owned power producer KEK, but “instead of offering cooperation, we have been attacked and labelled in the harshest ways by institutional leaders”.

The chamber has also gathered signatures for a petition to parliament and reached out to international actors. “We have addressed the EU Office in Kosovo, the European Union in Brussels, the European Commission and the Energy Community Secretariat in Vienna on this matter, and we are awaiting their response,” Ahmeti said.

The risks for Kosovo’s economy, according to businesses, are significant. A 16.1% increase in electricity prices earlier this year had already raised production costs. Liberalisation is now compounding the problem by forcing firms to negotiate contracts in a poorly regulated environment.

“Production costs have risen significantly, which in turn has increased product prices. Now, with energy liberalisation, businesses risk losing markets, facing lawsuits due to the impossibility of producing at the same price for external partners, significant job losses, and further price increases of goods, placing an even greater burden on consumers. This process, unfortunately, also risks deepening the trade deficit between imports and exports,” the executive director warned.

Kosovo already suffers from a persistent foreign trade deficit, with imports far exceeding exports, and higher production costs risk widening the gap further.

Missteps on the path towards EU standards

Liberalisation is formally aligned with the Energy Community Treaty, which obliges Kosovo to open its energy market as part of the EU integration process. However, the manner of implementation has generated instability rather than the intended efficiency gains.

Instead of a phased transition, businesses were given three months’ notice. Instead of structured competition, the market saw a rush of last-minute licensing. And instead of broad consultation, the reform was announced through the media.

The outcome is that companies face disconnections, uncertainty and higher costs, while regulators and suppliers struggle with credibility.

The current crisis cannot be understood without recalling Kosovo’s troubled energy history. Since the end of the independence war in 1999, the Kosovo Energy Corporation (KEK) has struggled with debts, underinvestment, and technical losses in the grid. Despite having some of the largest lignite reserves in Europe, Kosovo has long been a net importer of electricity due to outdated plants and frequent breakdowns.

The A and B units of the Kosova power plants in Obiliq have been plagued by outages, forcing costly imports, particularly during winter peaks. Bill collection has historically been weak, compounded by political disputes over unpaid electricity bills in the Serb-majority north. International donors have repeatedly pressed for reforms, yet efforts to restructure KEK or attract private investors have largely stalled.

Distribution was privatised in 2012 when Turkish consortium Limak-Calık took over KEDS, but businesses and consumers alike have complained of underinvestment and poor service. Blackouts, voltage fluctuations and high network losses remain common complaints.

Against this backdrop, the move to liberalise the market was framed as a way to attract new suppliers, increase efficiency and align Kosovo with EU energy directives. However, without first fixing long-standing weaknesses — from grid reliability to institutional transparency — the reform has exposed businesses to more risks than opportunities.

The next months will be crucial. Businesses are pressing for a review of the criteria and a transparent reassessment of suppliers. Courts may still rule on pending challenges, though disconnections continue in the meantime. International institutions, particularly the EU and the Energy Community, could step in to mediate and insist on a more gradual approach.

Liberalisation, if mishandled, risks driving companies out of the market, fuelling unemployment and undermining growth. On the other hand, if properly managed, it could help align the energy sector with European standards and attract investment.

For now, as the chamber’s warnings highlight, Kosovo’s electricity market reform is seen less as a step towards integration than as a source of disruption. Without greater transparency, consultation and regulatory capacity, the promise of liberalisation may remain elusive – and the costs borne by businesses and consumers alike.

Features

Turkmenistan’s TAPI gas pipeline takes off

Turkmenistan's 1,800km TAPI gas pipeline breaks ground after 30 years with first 14km completed into Afghanistan, aiming to deliver 33bcm annually to Pakistan and India by 2027 despite geopolitical hurdles.

Looking back: Prabowo’s first year of populism, growth, and the pursuit of sovereignty

His administration, which began with a promise of pragmatic reform and continuity, has in recent months leaned heavily on populist and interventionist economic policies.

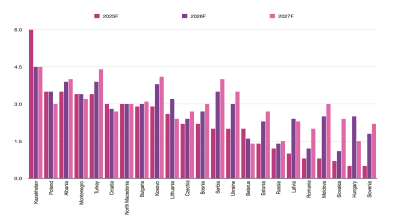

Emerging Europe’s growth holds up but risks loom, says wiiw

Fiscal fragility, weakening industrial demand from Germany, and the prolonged fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine threaten to undermine growth momentum in parts of the region.

The man who sank Iran's Ayandeh Bank

Ali Ansari built an empire from steel pipes to Iran's largest shopping centre before his bank collapsed with $503mn in losses, operating what regulators described as a Ponzi scheme that poisoned Iran's banking sector.