Kazakhstan's leader Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has repeatedly vowed to “turn Kazakhstan into a fully digital nation within three years”. The economy will be modernised and governance will be streamlined, he says.

Official sources claim some tangible results: since 2021, digital reforms have purportedly pulled tens of billions of tenge out of the shadow economy and saved public funds by delivering faster, more transparent services. Public services in Central Asia's largest economy today operate largely online – reportedly, 92% of government services are available digitally, cutting red tape and accelerating transactions. Moreover, officials claim that a recent focus on e-health, online schooling and other digital services has yielded large fiscal benefits.

Officials paint the digital strategy as a win-win that leverages artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain and e‑government tools to boost economic growth and turn Kazakhstan into a regional tech hub. The government’s strategy encompasses everything from AI labs and supercomputers to expanded connectivity and a proposed national digital currency. Foreign and domestic investment has flowed into projects like the Alem.AI research centre and Kazakh-language large-language models (LLMs), and even a planned national “digital tenge” currency.

But here's the double-edged sword – many of these initiatives rely on centralising citizen data. The assembled infrastructure is shaping up to be a vast surveillance and data-collection apparatus.

Digital surveillance state

Tens of thousands of facial-recognition cameras are already deployed nationwide, feeding government databases as part of what officials describe as “smart policing” and “predictive monitoring”.

Domestic companies such as Target AI, which developed the TargetEYE facial-recognition system now used by police in eight regions, have been promoted as local innovators. “In most cases, our company has no information about for what purposes or how the platform’s technical functions are applied,” Target AI told RFE/RL.

Commercial capital and largest Kazakh city Almaty alone has more than 128,000 cameras connected to Target AI systems, while the northeastern Pavlodar region is expanding its network with thousands more. The Defence Ministry has installed around 14,000 cameras in state buildings. The Interior Ministry, meanwhile, talks about all video data as being “protected by modern means” within a “closed contour.”

The surveillance technology has been extended into Kazakhstan’s experimentation with smart-city models. Sergek, an AI-based traffic monitoring network, has expanded beyond the capital Astana, while Smart Aqkol — a pilot “safe city” launched in partnership with Kazakhtelecom, Eurasian Resources Group and Tengri Lab — connects AI-powered cameras with police terminals and command centres for real-time monitoring.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, left, and Kazakh counterpart Kassym-Jomart Tokayev say only good things are coming down the Digital Silk Road. Privacy advocates are not so sure (Credit: Kazakh presidency).

Coda Story reported on how Smart Aqkol’s hardware “came through an agreement under China’s Digital Silk Road initiative,” and that the system uses surveillance cameras from Chinese firms Dahua and Hikvision. The broader Sergek network is also based on Chinese technology, according to a report by Civicidea.ge, with CCTV networks in major cities installed by Kazakh company Korkem Telecom with Dahua as the technical partner. Hikvision equipment has likewise been used in Almaty’s unified video-monitoring system with facial and licence-plate recognition functions. Analysts note that “Chinese products are mainly used” across Kazakhstan’s smart-city CCTV systems, according to Civicidea.ge’s report.

In a similar vein, Huawei and ZTE have partnered with Kazakhtelecom, Kcell and Beeline to develop 5G and smart-city networks. Civicidea.ge noted that “leading Chinese video surveillance companies such as Hikvision, Dahua and Huawei are among the main providers of surveillance services and technologies in developing countries, including Kazakhstan.”

The worry is that digital states of the future will obtain AI-based powers that no-one should have (Credit: bne IntelliNews).

Leaked documents have also exposed the extent of Chinese involvement in online monitoring. Exclusive.kz reported on analysis by InterSecLab that showed Kazakhstan was the first foreign client of China’s Geedge Networks in 2019 for an Internet surveillance system modelled on Beijing's Great Firewall. By 2020, Geedge nodes were reportedly operating in 17 cities across Kazakhstan. In late 2024, Politik.uz reported new shipments of Chinese optical bypass filters for internet traffic under the Geedge/TJJ-Company “Cybershield of Kazakhstan” project.

In September 2024, InterSecLab researchers analysed over 100,000 internal files from Geedge and concluded that Kazakhstan’s internet filtering system originated in China. RFE/RL’s report said that the Committee for National Security referred its questions about the findings to the Ministry of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Development. It dismissed the reports, stating that the information “does not correspond to reality.”

InterSecLab analyst Marla Rivera told TengriNews that Geedge’s system “gives the government a power that in principle no one should have. It’s very frightening”.

'China not a model for democratic society'

Kazakhstan’s cooperation with Beijing continues under the Belt and Road Initiative’s “Digital Silk Road.” This year the government announced a $21mn joint AI laboratory with China, deepening technical and financial ties.

Malikova told RFE/RL that “China, both politically and socially, is not a model for how technology should be used in a democratic society.”

While Chinese suppliers dominate the Central Asian state’s surveillance tech, other foreign firms are also entering Kazakhstan’s market. Swedish Axis Communications, South Korea’s Hanwha Vision and UAE-based Presight AI have signed recent contracts. Presight AI, a state-backed Emirati company, secured a deal to replace the Sergek system in Astana with 22,000 cameras linked to its own software.

At the same time, biometric systems are expanding into daily life. Residential complexes now use Face ID entry systems, and a national biometric authentication platform is being rolled out across banks, telecoms and public services. Since August 2024, banks have been required to verify online loans through biometric data.

In the financial sector, partnerships between Kazakh firms and foreign tech (such as Bybit and Biometric.Vision) are pushing biometric know-your-customer/anti-money laundering (KYC/AML) checks for crypto and even cash transactions.

AInvest.com cited cybercrime consultant David Sehyeon Baek as saying that, while these measures tighten oversight of illicit finance, they risk creating a “total financial visibility” for authorities if proper safeguards are not in place.

RFE/RL cited King’s College London researcher Oyuna Baldakova who warned that centralised biometric databases pose security risks: “Over time, you will have a level of data where the state can get involved and track people.”

Civic activist Assem Zhapisheva of the Oyan, Qazaqstan movement offered a sardonic view of biometric ticketing to Eurasianet: “How do you quickly assemble a database with biometric data and avoid getting flak for it? … Make payments on the bus with your face, of course!”

Security hawks take lessons from "Bloody January"

Though most developments described are relatively recent, Kazakhstan’s embrace of high-tech surveillance intensified after the "Bloody January" 2022 unrest when protests over fuel prices escalated into violent clashes across parts of the country, leaving more than 230 people dead. In a February 2022 address, Tokayev said: "We not only need to restore public order but also to increase the number of cameras. The issue is not full surveillance or monitoring of our citizens’ actions; this is a security matter.”

There are claims that during the "Bloody January" major social unrest and violence of 2022, 7,000 people were detained on the basis of data collected by street surveillance cameras (Credit: Fars news agency).

During the unrest, Kazakh sources described widespread use of Chinese surveillance technology. Bitter Winter reported in 2022, citing confidential information, that “all street cameras in Kazakhstan were made by the Chinese company Hikvision,” and that “China has sent a special team to Kazakhstan to help with face recognition and identify the protesters” using Chinese AI systems.

Coda Story similarly reported that “China had sent a video analytics team to Kazakhstan to use cameras it had supplied to identify and arrest protesters.” Human rights lawyer Danil Bekturganov said about 7,000 people were detained “based on data from street surveillance cameras” during the unrest, questioning official claims that no AI facial-recognition systems were used: “Given the scale of the protests … this is hard to believe,” he told Civicidea.ge.

Is a fully digital state even possible?

While the expansion of surveillance tech is likely to continue throughout Kazakhstan, questions remain open over the possibility of building a fully digital state, as desired by Tokayev.

Baldakova told RFE/RL that Kazakhstan still faces a digital divide between urban and rural regions, thus lacks capacity for a wholly digital state.

Though there are efforts to expand internet access via satellite constellation services, such as Elon Musk’s Starlink, which recently officially started operating on the territory of the ex-Soviet country, Kazakhstan faces deeper infrastructural issues. One of these is ageing Soviet infrastructure that appears to be on its last legs, as demonstrated during a citywide electricity and heating shutdown in Ekibastuz in December 2022. The power outage lasted for 10 days, but Ekibastuz is subject to routine power outages throughout the year nearly every year. Tokayev’s government is mostly betting on nuclear energy to deliver Kazakhstan from its energy woes, but that is only expected to happen from the mid-2030s.

Without sufficient energy capacity, the dream of running an efficient digital state seems unrealistic. It also does not help that the quality of internet services in Kazakhstan is rather lacking, despite the country ranking 45th globally in terms of mobile internet speed and 84th in terms of fixed broadband speed, according to Ookla’s August 2025 speed test. This issue is often felt by Kazakh citizens during working hours on weekdays and is often a topic of ridicule on the country's social media.

Indeed, can a truly efficient digital state, whether a surveillance state or not, even be possible without proper energy and internet infrastructure to sustain it and back it up – especially, in a country with a stark digital divide between rural and urban regions?

Tech

Romanian startup .lumen wins €11mn EU grant to develop autonomous delivery robots

Funds to back project aimed at developing a new generation of humanoid and quadruped robots capable of navigating pavements and crowded urban areas autonomously.

Latvian fintech Eleving Group raises €275mn in oversubscribed bond issue

Proceeds to be used to refinance €150mn in existing bonds and to expand Eleving's loan portfolio.

Roblox, Fortnite banned in Iraq over child safety concerns

Iraq's Ministry of Interior to ban PUBG, Fortnite and Roblox within next few months under 2013 law prohibiting games encouraging violence, citing threat to social security and waste of youth time.

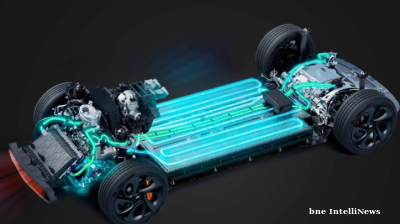

China’s solid-state battery breakthrough challenges the future of petrol-powered cars

Chinese researchers have announced a breakthrough in solid-state battery technology that could accelerate the global shift away from internal combustion engines, with a new design that more than doubles the range of current electric vehicles.