Turkey’s populist authoritarian leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is fighting for his political survival, says a Council on Foreign Relations academic and analyst in a May 29 article published by Foreign Affairs titled, “The End of Erdogan: How the Turkish Leader Has Engineered His Own Undoing.”

Looking at Erdogan’s “predicament” since in the early hours of March 19, he “orchestrated a raid on the home” of Ekrem Imamoglu, Istanbul’s popular mayor and his chief political rival, who was arrested and indicted on “highly dubious charges, including baseless accusations of corruption and terrorism”, Henri J Barkey argues: “The charismatic and competent Imamoglu may be a uniquely threatening rival. But in truth, Erdogan’s decision to arrest Imamoglu did not create this crisis. It reflected a growing weakness.

“Erdogan was already confronting mounting public fatigue with his presidency. His hubris and domineering leadership style have eroded the once broad enthusiasm for his rule, making him ever more desperate to constrain a now irrepressible dissatisfaction. A March 2024 Pew Research Center survey found that 55 percent of Turkish adults held an unfavorable opinion of Erdogan, and his party lost the 2024 municipal elections.

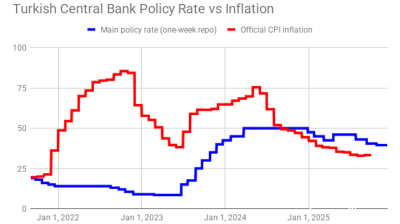

“The depth, scope, and duration of the recent protests [against the move on Imamoglu, who remains imprisoned] are new: the demonstrators fused their street protests with organized boycotts of pro-Erdogan businesses, online activism, and civil disobedience. Imamoglu’s arrest also brought fresh instability to Turkey’s already struggling economy.

“Erdogan has responded by doubling down and arresting, on a rolling basis, hundreds of Imamoglu’s associates, including colleagues, friends, former business partners, members of the Turkish business community, and family members. But these repressions now seem less like the acts of a potent authoritarian and more like the flailing of a threatened, insecure, and imperiled man.”

Imamoglu remains in jail, but 'it is Erdogan who is trapped'

Although Imamoglu remains in jail, it is Erdogan who is trapped, says Barkey, contending that his deepening unpopularity have diminished his ability to change the constitution or force early elections, the two legal options he can take to find a path that would enable him to extend his presidential tenure.

Four years from now when his current presidential term runs out, Erdogan will almost certainly no longer be president, predicts Barkey. “The fact that so many young Turkish citizens dared to demonstrate against him reflects the irrevocable degradation of his popularity.

“As the only leader these youth have ever known, he once seemed eternal, a fact of life. But no longer: his own missteps have doomed him. Polls suggest that if elections were held in Turkey tomorrow, he would not win. Regardless of future developments, Erdogan’s legacy will likely be defined by his decision to imprison his principal opponent—and serve as an example of how even the most formidable authoritarian leaders can overstep.”

In Barkey’s eyes, “until Imamoglu arrived on the scene, Erdogan had managed to turn bouts of public opposition or the emergence of competitors into excuses to further strengthen his authority”.

He adds: “Although he cultivates an image of omnipotence and infallibility, Erdogan is exceptionally thin-skinned. Turkish jails now overflow with politicians, journalists, academics, and citizens whose words or actions have been construed as offensive or oppositional.

“Individuals often languish in detention for months, awaiting trial for alleged offenses as trivial as a social media post from years past deemed insulting to the president. Between 2014 and 2020 alone, Erdogan’s government investigated approximately 160,000 Turks for insulting the president and prosecuted 35,000.”

Imamoglu, notes Barkey, “is the first politician in years to seriously jeopardize Erdogan’s hold on power” and Turkey’s leader of 22 years now wants to outlast the crisis provoked by jailing him “by relying on brute force, as he did during the 2013 Gezi Park protests. But his overreach has unintentionally united and energized the Turkish opposition. Labeling protests and economic boycotts terrorism or treason or banning marches is less successful today, because the opposition now has an appealing leader in Imamoglu as well as a unifying idea: that Turkey deserves a chance at building a democracy”.

“The longer Imamoglu remains imprisoned, the more his stature grows. It is only a matter of time before comparisons between him and figures such as Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim or the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel are drawn,” Barkey assesses.

And he concludes: “The fact is that the indomitable Erdogan has run out of room to maneuver. By choosing the time and manner of his exit, he could help ease the transition to a new leader and ensure Turkey is at peace with itself. He can still shape his legacy.

“His personality, however, suggests that he is unlikely to embark on such a shift. If he sticks to his typical approach, there is a significant risk that the Turkish public will turn decisively against him—and that his long, eventful tenure in office will be remembered more simply as an era of autocracy.”

Henri J Barkey is Cohen Professor of International Relations Emeritus at Lehigh University and Adjunct Senior Fellow for Middle East Studies at the New York-headquartered Council on Foreign Relations.

Opinion

Don’t be fooled, Northern Cyprus’ new president is no opponent of Erdogan, says academic

Turkey’s powers-that-be said to have anticipated that Tufan Erhurman will pose no major threat.

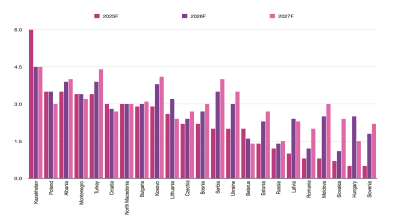

COMMENT: Hungary’s investment slump shows signs of bottoming, but EU tensions still cast a long shadow

Hungary’s economy has fallen behind its Central European peers in recent years, and the root of this underperformance lies in a sharp and protracted collapse in investment. But a possible change of government next year could change things.

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.