ED - This article is part of a series looking at the affordability of increasing European defence spending and funding the war in Ukraine.

See the accompanying articles:

LONG READ: Europe can’t afford the Ukraine war

LONG READ: Europeans face recession, financial crises, as they struggle to boost defence spending

US President Donald Trump has dropped the burden of supplying and supporting Ukraine’s battle against Russia firmly in Europe’s lap. At the same time as the recent Nato summit in the Hague he demanded, and got, a commitment to increase spending on their own defence sectors to 5% of GDP, up from the 2% everyone has been ignoring for years. Soaring defence spending comes on top of soggy economic performance thanks to the cumulative pressure of ballooning polycrisis debt and the Russian sanctions boomerang effect. Europe is being driven into recession and now some of the leading powers are facing full blown financial crises.

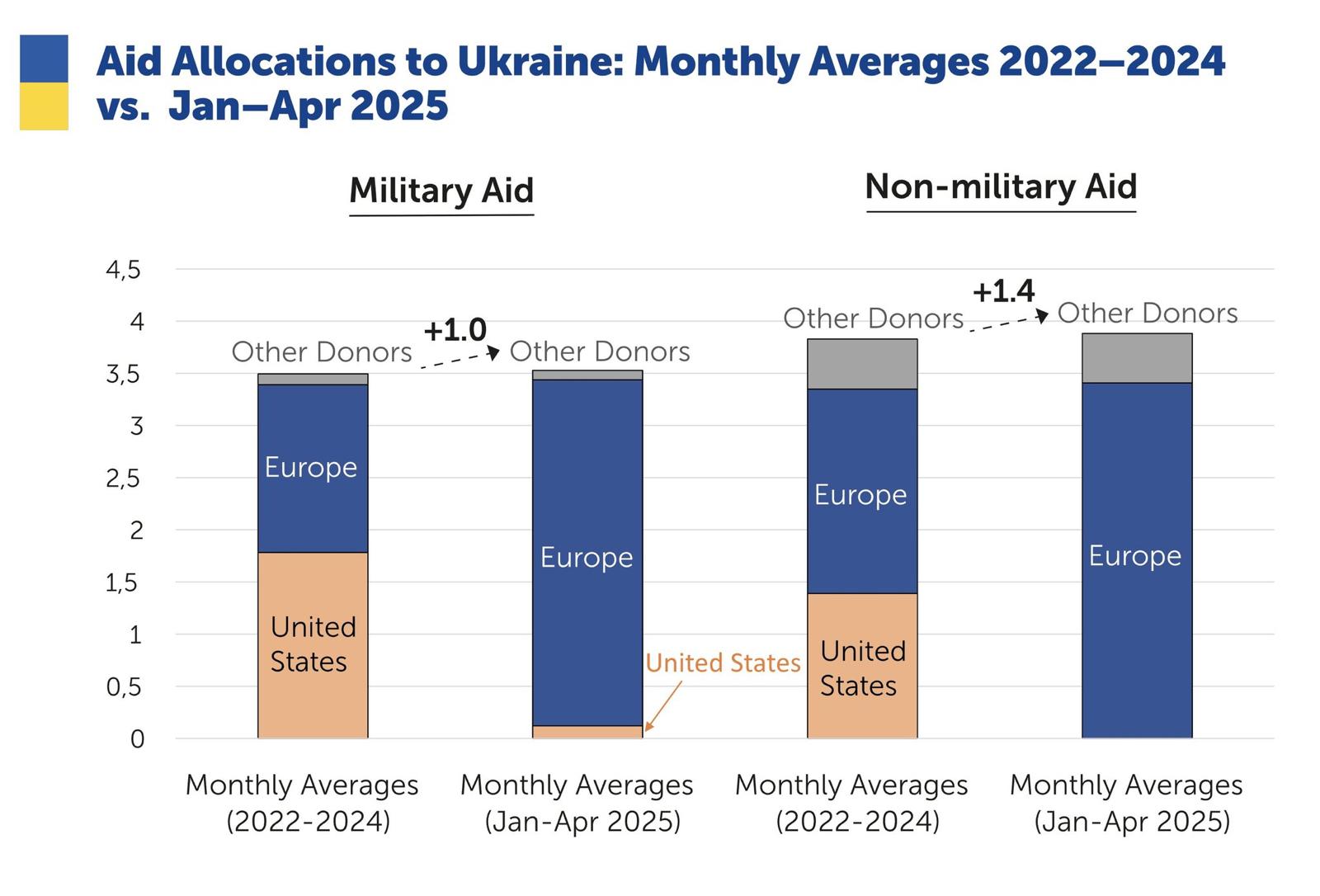

The amount of money Europe needs to find is enormous. The cost of the war is running at an estimated $100bn a year, according to Timothy Ash, the senior sovereign strategist at BlueBay Asset Management in London. And since Trump took over Europe has taken on this entire burden.

The new Nato spending target is going to be phased over the years to 2036, but even raising spending to the more immediate goal of 3.5% of GDP that should specifically be spent on weapons will require additional spending of $250bn a year. European defence spending has already surged and this year is expected to overtake US spending for the first time since WWII. However, it will total €170bn vs US spending of €168bn, which is still less than the €250bn needed.

The German-led Zeitenwende, or military “change of the times,” is well under way and the question remains: will it be enough to meet Russia in the field?

In 2016 only three of the 32 Nato members were meeting the Welsh 2% of GDP spending requirement, imposed in 2014. Today 31 members spend that much, according to the latest Nato data, but to catch up with Russia, which is outpacing Europe in weapons production, spending needs to rise quickly to 3.5% in the short- to medium-term and most European governments are going to struggle to hit that target. To fund the increases, most member states will be forced to cut further into domestic spending as well as borrowing heavily – something that only a few countries like Germany and Poland can afford to do.

To ease the pain, Brussels is relaxing its borrowing cap rules, bring in the European Investment Bank (EIB) to make defence sector “loans” that won’t end up on the national balance sheet, and has rolled out a new one-time €150bn SAFE (Security Action for Europe) defence loans facility. Member states could raise another €650bn from the relaxed borrowing cap rules, after the European Commission (EC) activated the Stability and Growth Pact’s “national escape clause”, also dubbed “financial flexibility.” Together this will make up €800bn of defence spending through to 2030. But all this money is a one-off change that is spread out over five years, not the additional €250bn a year that is needed.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen admitted that currently Russia produces arms in three months that takes the EU and Ukraine combined a whole year to make in her ReArm speech (video) on March 4.

And that is just defence spending. The Draghi report from former Italian Prime Minister and ex-European Central Bank boss last year detailed how Europe has lost its competitive edge. He recommended that the EU invest €800bn per year to catch up or face falling inexorably behind the other leading economies of the world, dooming Europe to Argentina’s fate in the last century.

An important point to note is that Draghi’s call for €800bn of investment per year to improve Europe’s competitiveness has been lost in the noise of the need to rearm Europe. None of the governments in Europe earmarked cash for the heavy investment into innovation needed to catch up with either China or the US. What is being done are some bureaucratic reforms to improve the efficiency or cut red tape, and trim the most onerous of the Green Deal regulations as agriculture makes up a third of EU budget spending. But these Draghi reforms, which should be front and centre, are peripheral at best and being largely ignored.

Even with the EU’s proposed total defence spending of €800bn over the next five years, the only way that member states can come up with the extra cash needed to cover procurement bills is to cut deeply into their domestic budget expenditures as well as borrow heavily.

Germany’s heavy lifting

As Europe’s biggest country and economy, Germany will have to do a lot of the heavy lifting in the ReArm programme. It has a standing army of slightly more than 200,000 active servicemen, with a long-term target of 300,000 under its expansion plans. There is even talk of reintroducing national service to bolster the numbers. But it would face a million-strong Russian invading force that the Kremlin says it wants to increase to 1.5mn. That is before Putin introduces a general mobilisation to draw on his 144mn-strong population, something he has been very reluctant to do so far.

As Europe’s richest country, even Germany is struggling financially. The economy has contracted for the last three quarters in a row and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz admitted in August that “solving the economic problems is proving tougher than we thought.” Caught between the rock of trying to take over the US mantle to protect Ukraine and the hard place of funding a stagnant and deindustrialising economy, Merz has no good options.

With a deficit of 2.5% of GDP and rising, the Chancellor is being forced to make cuts at home at the same time as is planning to invest €150bn into modernising the Bundeswehr and give Kyiv €50bn in aid. Even with new borrowing capacity, after the so-called Schuldenbremse, restrictions on government borrowing, were lifted just before he took office, Berlin is also strapped for cash.

Defence spending is currently at 2.4 % of GDP, and the Bundestag has already approved a significant €100bn of new defence spending that should allow it to hit the interim target of 3.5 % by 2029 via nearly €400bn of borrowing.

That is possible thanks to the relaxation of the constitutional Schuldenbremse restrictions and Germany’s moderate debt‑to‑GDP ratio of 69 %. But debt-to-GDP will rise fast and this still doesn’t produce much money for the modernisation investments Draghi is talking about. Interest payments could hit €71 bn annually by 2035, according to Bruegel and to move from 3.5 % to the full 5 % Nato target would require an additional €70–80bn of annual spending that would push debt-to-GDP up to 84 % by mid‑2030s.

Rise of the right

The attempt to rearm Europe is going to pour fuel on dissent and the rise of right-wing politics in Europe. "For the first time, populist or far-right parties are leading the polls in the UK, France and Germany, the latest sign of growing voter discontent across much of the continent following years of high immigration and inflation,” The Wall Street Journal reported on September 1.

Political pressure on Merz is already mounting. In August, German unemployment rose to its highest level in ten years. The number of out of work people topped the three-million mark for the first time since 2015 in July, “providing further evidence that a long period of economic stagnation eventually takes a toll on the labour market,” ING said in a note.

“A full reversal of previous US front-loading effects has pushed the German economy back into recessionary territory, and it looks increasingly unlikely that any substantial recovery will materialise before 2026,” Capital Economics also said in a note.

The country’s economy can no longer afford to finance the current social welfare system, Merz said last month and called for a review of the benefits system, which cost a record €47bn last year. He is mulling cuts to housing and child allowances, unemployment payments, family supplements, aid programs for the needy, and subsidies for caring for the sick and elderly. The right-wing AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) immediately drew their knives and has been roasting the Chancellor for prioritising Ukrainians over Germans: since February 2022, Germany has provided a total of €50.5bn to support Ukraine, about a third of the EU’s total contribution of €170bn, and a bit less than twice the amount the US has contributed.

Merz’s policies are a sharp reversal from former Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who attempted to balance the budget, announcing last year he was cutting Berlin’s contributions from €3bn a year in 2025 to $500mn for the next two years. Merz has promised to continue to provide Kyiv with more than €8bn annually in bilateral military aid until 2027.

The AfD came in in a strong second place in recent regional elections with 20% of the vote and now have overtaken Merz’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in the polls, putting the pro-Russian party on track to win the next elections.

UK Ponzi scheme

Both France and the UK are already in deep financial trouble and will not be able to expand military spending by anywhere near what is needed.

UK long-term borrowing costs hit a 27-year high on September 2 as 30-year gilt yields surged to 5.7% — 15x higher than 2020 lows. Markets fear Labour is losing control of public finances: spending is set to climb above 60% of GDP while revenues fall below 40%, threatening to push debt above 200% of GDP by 2073, according to some economists.

“Britain's public finances are starting to resemble a Ponzi scheme,” Daily Telegraph columnist and bne IntelliNews contributor, Liam Halligan, said in a recent social media post. “This week's official fiscal report for June reveals that no less than four-fifths of the money the UK government is borrowing is now being spent on interest payments on existing debt.

The UK already pays more in debt servicing than for every spending item in the budget apart from health. Britain is heading towards a 1970s-style debt crisis, and a bailout from the IMF, The Sunday Telegraph reported in August.

The UK’s debt is becoming unsustainable, according to Halligan, while the lack of investment and innovation has left growth stagnant. Indeed, stagnation is already giving way to the even more damaging stagflation. Inflation is back up to near 4%, double the Bank of England target, yet the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street has been forced to cut rates because growth is flat. The mix of high debt, rising prices, and weak growth points to worsening stagflation that stymied the UK in the 1970s. The UK’s problems suggests a global bond crisis is spreading to the major developed world economies grappling with the polycrisis that includes the knock on effects of sanctions on Russia and Trump’s escalating trade war. The UK’s GDP per capita growth collapsed from 2.5% to 0.7% annually this year – the worst decline in the G7 except Italy.

“The root cause? Stagnant labour productivity, rising merely 6% since 2007 versus 22% in the US and 10% in the Eurozone,” Halligan said. “Neither Britain's market nor state functions effectively.”

Like Germany, British demagogues like Micheal Farage have leapt into the breach and are making political hay out of the economic collapse. Long a loonie fringe figure, Farage’s Reform UK party has emerged to top the polls and could also take power in the next elections.

“They peddle quick fixes: Brexit promises, unfunded tax cuts, and sovereignty myths. While moderates acknowledge the problems but avoid confronting the crisis's scale, preferring to manage the decline rather than reversing it,” Halligan says.

France’s IMF bailout

France is in even worse shape than the UK. Both France and the UK are in budget crises and both have said in the last two weeks they are facing Greek-like debt problems and may be forced into the humiliation of asking the IMF for a bail out loan – something more characteristic of an Emerging Market than a former Empire.

Finance Minister Eric Lombard is struggling with a record national debt of €3.3 trillion, a debt-to-GDP ratio of 113% and a budget deficit of 5.8%. It has no way to reduce any of these numbers. France has never required an IMF bailout before. Long-term borrowing costs have soared this week to their highest level since 2011, as investors’ confidence in the Elysée Place’s ability to deal with the mounting fiscal problems evaporates.

France’s deficit problem is so bad that after Prime Minister Francois Bayrou's gamble to win backing for his deeply unpopular debt-reduction plan backfired, his government looks certain to fall during a no-confidence vote on September 8.

He said of the IMF bailout on August 26: “It is a risk that we would like to avoid, and one that we should avoid. But I cannot tell you that this risk does not exist.”

Like Germany, France also ran out of money for Ukraine in October last year. It had also pledged €3bn a year but cut that to €2bn the Defence Minister Sébastien Lecornu said at the time. No new commitments have been made since. And like Germany and Britain, resentment at spending billions on Ukraine and not at home is rising.

France’s largest opposition party, the far-right National Rally, has its knives out too and called on President Emmanuel Macron to call new elections or resign ahead of the likely collapse of the government.

“Emmanuel Macron must recognise this institutional paralysis that he himself has caused and either dissolve the National Assembly or, obviously, submit his resignation,” Jordan Bardella, the president of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally said in an interview the same day.

“France's fragile coalition government looks set to lose a confidence vote scheduled on September 8. Consequently, Prime Minister François Bayrou's deficit target of 4.6% of GDP now seems dead in the water, and the next government's target will likely be much more modest, confirming our view that France cannot undertake meaningful fiscal consolidation in the current fractured political environment,” Oxford Economics said in a note. “Bayrou's failed gamble supports our view that there is no consensus on how to reduce France's deficit and no viable political path to achieve meaningful fiscal consolidation at present.”

The heart of the problem in Germany, France and the UK is, as Draghi highlighted, decades of complacency and underinvestment, thanks to the end of the Cold War “peace dividend” that hollowed out Europe’s power, despite its nominal size.

The European Union can no longer believe its big economy brings it global power and influence. “This year will be remembered as the year in which this illusion evaporated,” Draghi said in a speech in August.

Italy ignoring the problem

A right-wing party has already taken control of Italy, Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy, but she has been one of the more rational voices in the current debate on providing Ukraine with real security guarantees. While France and Britain are suggesting the unworkable option of a Nato-led “reassurance force”, Meloni has called for genuine bilateral “Nato-lite” security guarantees that include military commitments.

The Italian Army has an active strength of about 96,000 men and women, of which around 56,000 are fully operational combat soldiers assigned across its ten brigades. But when it comes to beefing up the military, Italy is in as bad a situation as France and Britain. Italy already spends the least in Europe on defence, only 1.6% of GDP. To get to Nato’s 3.5% target, Rome would need to increase spending by circa €60bn a year.

At the same time, it has the highest debt-to-GDP ratio of a major EU power of 137% that will make borrowing more to spend on arms next to impossible. If Rome did try to borrow to pay for military spending, then its debt‑to‑GDP would see one of the largest increases of all Nato members —in the range of 3 to 3.5 percentage points, according to Capital Economics estimates, from its already extremely high levels.

Interest payments already account for roughly 7.7 % of total government expenditure in 2024, according to Eurostat, which is slightly less than the UK’s 8.3%, but Italy runs a consistent current account surplus, due to things like tourism, taking the pressure off a little.

On the external side, Italy’s gross external debt reached €2.69 trillion in early 2025, slightly higher than at the end of last year and on a par with France.

Public finances are improving after a sharp setback in 2023, when the budget deficit swelled to 7.4% of GDP due to the reclassification of housing renovation incentives. Rome expects a budget deficit of 4.3% of GDP this year, 3.7% next year and 3.0% in 2026, although the country's finance minister has said much would depend on the European Union's new budget rules.

Following this summer’s Nato summit, defence spending is set to rise in line with the commitments to the Trump administration. Italy allocated around 1.5–1.6% of GDP to defence in 2024, but the government has pledged to lift this to 2% in 2025.

But Rome doesn’t seem to be taking the pledge to increase spending seriously. Part of the increase to 2% will be achieved by “accounting changes,” Meloni’s government says. At the same time Italian politicians are proposing to build a long-discussed €13.5bn bridge to Sicily, the world's longest suspension bridge, that they want to classify as “military infrastructure expenditure.” Critics complain the bridge doesn’t make sense as a military project and is just a way for Rome to pretend it’s boosting defence spending. The project has been the dream of the Romans, dictator Benito Mussolini and former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, but many say it will do nothing for Europe’s defence.

Poland & Finland

The only two countries that are anywhere near ready for a war with Russia are Poland and Finland. Both have been invaded by Russia before and both, unlike the rest of Europe, have kept themselves war-ready for years.

Finland maintains a standing army of around 20,000 men but thanks to compulsory national service can field a quarter of a million men. And its army is probably one of the best trained, best equipped armies in Europe.

Poland also takes its commitment to defence seriously and is in the process of building up the largest conventional army in Europe. It is already spending close to 5% of GDP on defence and will reach the new Nato target as soon as next year without breaking a sweat.

It has to take a Russian invasion seriously as it will almost certainly find itself in the front line and need to rebuff the initial attack. It has always been assumed that a Russia attack will form via Poland’s Suwałki Gap, a sparsely populated strip of land between Poland and Lithuania that separates Russia's Kaliningrad Oblast from Belarus - an Achilles’ heel for Nato. In addition to spending heavily on new equipment, Warsaw has recently also floated the idea of rehydrating its peatlands in the gap to bog down tank and troop movements in the mud.

And Poland has the money. The economy is forecast to be Europe's fastest growing economy this year, expanding by 3.5%. The economy is not perfect as its budget deficit is projected to be 6.5% of GDP this year – about three times higher than Russia’s – but the government is already working to bring the deficit down. Debt in Poland is also low as it is constitutionally capped at 60%, and currently a very modest 53.3% of GDP.

Finland spent above average 2.3% of GDP on defence, or $6.7bn in 2025. Fully mobilised Finland can field up to 300,000 men very quickly, making it one of the largest per capita defence forces in Europe.

Given that initial fighting will probably happen in northwest Europe, the combined Polish and Finnish armies will be able to significantly slow, or even stop, a Russian advance in its tracks - temporarily. But Putin’s “meatgrinder” tactics of simply and continuously throwing men into the frontline irrespective of the casualty rate to wear down the opposition thanks to Russia’s 150mn-strong population, mean that Poland will have to be reinforced fairly quickly.

The problems start if a conflict with Russia is protracted. Due to Europe’s stunted defence production capacity, if a conflict drags on then Russia’s wartime industrial base will prove to be a significant advantage. For example, according to British intelligence reports, the UK will start running out of ammunition in less than two months, whereas Russia is now producing more than it needs for the Ukrainian conflict and stockpiling the excess. After more than three years of supplying Ukraine, Western allies say they are already running low on ammo. Rheinmetall CEO Armin Papperger told CNBC last week that Europe must act “fast” to catch up with Russia’s artillery ammunition output.

|

Nato members military personnel (thousands) |

||||||||||||

|

Country |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024e |

2025e |

|

Albania |

6.7 |

6.2 |

5.8 |

6.8 |

6.8 |

6.8 |

6.7 |

6.6 |

6.6 |

6.6 |

7 |

7.4 |

|

Belgium |

30.5 |

29.7 |

28.8 |

27.8 |

26.5 |

23.3 |

22.8 |

22.1 |

21.4 |

21.4 |

21.3 |

21.3 |

|

Bulgaria |

27.5 |

24.9 |

24.7 |

24.3 |

24.4 |

24.6 |

25 |

25.7 |

25.6 |

25.6 |

26.9 |

28.4 |

|

Canada |

65.9 |

70.3 |

70.5 |

68.2 |

70.3 |

71.8 |

70.3 |

68.2 |

67.4 |

66.8 |

77.1 |

77.1 |

|

Croatia |

15.4 |

15.1 |

14.8 |

14.8 |

15 |

14.8 |

14.7 |

14.9 |

14.4 |

14 |

13.7 |

15.2 |

|

Czechia |

20.2 |

21.5 |

22.7 |

23.8 |

24.7 |

25.3 |

26.1 |

26.4 |

26.6 |

27.3 |

29.5 |

30.6 |

|

Denmark |

16.9 |

17.2 |

17.3 |

16.7 |

17.1 |

16.3 |

16.9 |

16.9 |

16.7 |

17.3 |

17.3 |

17.3 |

|

Estonia |

6.3 |

6 |

6.1 |

6 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

6.7 |

6.6 |

6.3 |

7.3 |

7.5 |

7.8 |

|

Finland |

32.5 |

31 |

31.3 |

31 |

31.8 |

31.1 |

31.3 |

31.1 |

30.5 |

31 |

30.8 |

30.8 |

|

France |

207 |

204.8 |

208.1 |

208.2 |

208.2 |

207.8 |

207.6 |

207.6 |

207.1 |

205.3 |

204.7 |

|

|

Germany |

178.8 |

177.2 |

177.9 |

179.8 |

181.5 |

183.8 |

183.9 |

183.9 |

183.2 |

181.7 |

185.6 |

186.4 |

|

Greece |

107.3 |

104.4 |

106 |

106.8 |

109.2 |

102.5 |

106.6 |

108.1 |

107.3 |

111 |

110.8 |

111.7 |

|

Hungary |

17.5 |

17.4 |

17.9 |

18.7 |

19.9 |

18.9 |

19.8 |

20 |

19.7 |

20.1 |

20.9 |

21.6 |

|

Italy |

183.5 |

178.4 |

176.3 |

174.6 |

174.1 |

176.4 |

173.4 |

170.3 |

170 |

170.7 |

171.4 |

171.2 |

|

Latvia |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.2 |

5.5 |

5.9 |

6 |

6.4 |

6.5 |

6.4 |

6.7 |

8.4 |

9 |

|

Lithuania |

8.6 |

11.8 |

11.8 |

13.5 |

14.3 |

14.9 |

15.1 |

15.2 |

15.7 |

17.9 |

18.5 |

19.5 |

|

Luxembourg |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

Montenegro |

1.9 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

2 |

|

Netherlands |

41.2 |

40.6 |

40 |

39.5 |

39.3 |

39.7 |

40.4 |

40.9 |

40.6 |

41.1 |

41.9 |

42.5 |

|

North Macedonia |

6.5 |

6.8 |

6.6 |

6.3 |

6.5 |

6.4 |

6.4 |

6.1 |

5.9 |

5.7 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

|

Norway |

21 |

20.9 |

20.5 |

20.2 |

20.2 |

19.2 |

20.6 |

23.1 |

23.5 |

24 |

24.3 |

24.8 |

|

Poland |

99 |

98.9 |

101.6 |

105.3 |

109.5 |

113.1 |

116.2 |

166.8 |

176 |

206.5 |

216.1 |

233.8 |

|

Portugal |

30.7 |

28.3 |

29.8 |

27.8 |

26.9 |

23.8 |

23.7 |

25.3 |

22.5 |

21.4 |

24 |

24.9 |

|

Romania |

65.1 |

64.5 |

63.4 |

64 |

64 |

64.5 |

66.4 |

68.6 |

66.7 |

64 |

66.6 |

69.3 |

|

Slovak Republic |

12.4 |

12.4 |

12.2 |

12.2 |

12.2 |

12.7 |

13.1 |

13.1 |

13.2 |

13 |

15.6 |

16.9 |

|

Slovenia |

6.8 |

6.6 |

6.5 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

5.9 |

6.1 |

|

Spain |

121.8 |

121.6 |

121 |

117.7 |

117.4 |

117 |

118.7 |

118.7 |

117.3 |

116.3 |

117.4 |

118.2 |

|

Sweden |

14.7 |

15 |

15 |

15.9 |

17.8 |

19.1 |

20.1 |

21.1 |

20.9 |

21.5 |

23.1 |

24.9 |

|

Türkiye |

426.6 |

384.8 |

359.3 |

416.7 |

444.3 |

441.8 |

433 |

450 |

455.9 |

463.7 |

481 |

494.5 |

|

United Kingdom |

168.7 |

141.4 |

139.5 |

149.4 |

146.6 |

144 |

147.3 |

148.2 |

143.6 |

138.1 |

138.1 |

|

|

United States |

1338.2 |

1314.1 |

1301.4 |

1305.9 |

1317.4 |

1329.2 |

1346.7 |

1349 |

1317 |

1286 |

1300.2 |

|

|

NATO Europe and Canada |

1890.8 |

1810.7 |

1788.3 |

1857.1 |

1893 |

1883.7 |

1896.7 |

1968.3 |

1968.2 |

2033 |

2114 |

1820.2 |

|

NATO Total |

3228.9 |

3124.8 |

3089.8 |

3163 |

3210.5 |

3212.9 |

3243.4 |

3317.3 |

3285.2 |

3319 |

3414.2 |

1820.2 |

|

source: Nato |

||||||||||||

Nato defence expenditure per capita USD

|

Country |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024e |

2025e |

|

Albania |

68 |

60 |

59 |

62 |

67 |

76 |

75 |

79 |

82 |

125 |

128 |

159 |

|

Belgium |

471 |

448 |

444 |

443 |

453 |

459 |

492 |

540 |

625 |

636 |

695 |

1090 |

|

Bulgaria |

126 |

125 |

130 |

132 |

162 |

366 |

180 |

187 |

216 |

270 |

282 |

306 |

|

Canada |

520 |

620 |

598 |

755 |

691 |

692 |

707 |

667 |

642 |

701 |

763 |

1052 |

|

Croatia |

248 |

248 |

236 |

255 |

251 |

272 |

266 |

351 |

346 |

331 |

384 |

431 |

|

Czechia |

218 |

248 |

235 |

267 |

292 |

321 |

333 |

372 |

357 |

364 |

574 |

568 |

|

Denmark |

704 |

693 |

731 |

741 |

845 |

866 |

897 |

903 |

961 |

1433 |

1663 |

2400 |

|

Estonia |

431 |

461 |

484 |

496 |

512 |

537 |

590 |

563 |

589 |

788 |

876 |

892 |

|

Finland |

721 |

721 |

724 |

726 |

734 |

778 |

799 |

749 |

907 |

1125 |

1263 |

1478 |

|

France |

764 |

753 |

762 |

772 |

797 |

811 |

817 |

834 |

835 |

877 |

924 |

940 |

|

Germany |

577 |

581 |

596 |

627 |

642 |

699 |

752 |

746 |

776 |

841 |

1041 |

|

|

Greece |

429 |

447 |

466 |

467 |

509 |

500 |

539 |

750 |

856 |

627 |

637 |

678 |

|

Hungary |

127 |

139 |

158 |

197 |

176 |

245 |

308 |

250 |

364 |

404 |

423 |

418 |

|

Italy |

393 |

370 |

416 |

432 |

445 |

428 |

530 |

559 |

579 |

573 |

587 |

793 |

|

Latvia |

155 |

179 |

257 |

299 |

406 |

403 |

417 |

435 |

467 |

624 |

708 |

803 |

|

Lithuania |

157 |

209 |

283 |

347 |

418 |

447 |

462 |

467 |

595 |

649 |

755 |

1008 |

|

Luxembourg |

475 |

535 |

503 |

647 |

651 |

718 |

737 |

635 |

757 |

942 |

1073 |

1780 |

|

Montenegro |

122 |

117 |

122 |

121 |

129 |

131 |

145 |

147 |

139 |

159 |

185 |

226 |

|

Netherlands |

613 |

612 |

637 |

646 |

697 |

768 |

779 |

796 |

873 |

998 |

1249 |

1570 |

|

North Macedonia |

69 |

69 |

66 |

62 |

68 |

87 |

90 |

111 |

124 |

135 |

157 |

172 |

|

Norway |

1361 |

1411 |

1550 |

1551 |

1563 |

1689 |

1769 |

1558 |

1384 |

1713 |

2143 |

3191 |

|

Poland |

257 |

318 |

295 |

294 |

331 |

341 |

375 |

407 |

435 |

647 |

774 |

948 |

|

Portugal |

293 |

304 |

296 |

300 |

334 |

351 |

333 |

375 |

364 |

354 |

424 |

545 |

|

Romania |

151 |

168 |

171 |

226 |

249 |

266 |

282 |

276 |

274 |

256 |

353 |

378 |

|

Slovak Republic |

181 |

214 |

219 |

223 |

256 |

366 |

398 |

378 |

402 |

416 |

454 |

486 |

|

Slovenia |

236 |

230 |

256 |

263 |

282 |

302 |

289 |

362 |

389 |

402 |

421 |

637 |

|

Spain |

264 |

276 |

247 |

284 |

296 |

293 |

288 |

313 |

367 |

382 |

478 |

676 |

|

Sweden |

596 |

582 |

563 |

566 |

573 |

621 |

636 |

868 |

908 |

1029 |

1413 |

1553 |

|

Türkiye |

109 |

109 |

117 |

129 |

157 |

160 |

162 |

154 |

136 |

156 |

231 |

258 |

|

United Kingdom |

971 |

934 |

971 |

985 |

1004 |

1006 |

1016 |

1069 |

1105 |

1086 |

1125 |

1164 |

|

United States |

2345 |

2262 |

2276 |

2178 |

2214 |

2422 |

2432 |

2479 |

2332 |

2294 |

2419 |

2469 |

|

NATO Europe and Canada |

466 |

472 |

483 |

510 |

527 |

545 |

568 |

583 |

602 |

647 |

752 |

868 |

|

NATO Total |

1119 |

1095 |

1108 |

1092 |

1116 |

1201 |

1220 |

1248 |

1209 |

1222 |

1329 |

1423 |

|

source: Nato |

||||||||||||

Nato national defence spending share of GDP %

|

Country |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024e |

2025e |

|

Albania |

1.33 |

1.15 |

1.09 |

1.1 |

1.15 |

1.27 |

1.29 |

1.24 |

1.2 |

1.75 |

1.7 |

2.01 |

|

Belgium |

0.97 |

0.91 |

0.9 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

1.01 |

1.04 |

1.16 |

1.18 |

1.29 |

2 |

|

Bulgaria |

1.31 |

1.25 |

1.24 |

1.22 |

1.45 |

3.14 |

1.59 |

1.51 |

1.59 |

1.94 |

1.95 |

2.06 |

|

Canada |

1.01 |

1.2 |

1.16 |

1.44 |

1.3 |

1.29 |

1.41 |

1.27 |

1.2 |

1.33 |

1.47 |

2.01 |

|

Croatia |

1.81 |

1.75 |

1.59 |

1.63 |

1.54 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.97 |

1.8 |

1.67 |

1.87 |

2.03 |

|

Czechia* |

0.94 |

1.02 |

0.94 |

1.02 |

1.09 |

1.16 |

1.27 |

1.35 |

1.29 |

1.32 |

2.08 |

2 |

|

Denmark* |

1.15 |

1.11 |

1.15 |

1.14 |

1.28 |

1.3 |

1.37 |

1.29 |

1.36 |

2 |

2.27 |

3.22 |

|

Estonia* |

1.9 |

1.99 |

2.03 |

1.97 |

1.97 |

2 |

2.26 |

2.02 |

2.14 |

3 |

3.37 |

3.38 |

|

Finland |

1.46 |

1.46 |

1.43 |

1.39 |

1.4 |

1.46 |

1.54 |

1.41 |

1.69 |

2.12 |

2.4 |

2.77 |

|

France |

1.82 |

1.78 |

1.79 |

1.78 |

1.81 |

1.82 |

1.99 |

1.9 |

1.87 |

1.94 |

2.03 |

2.05 |

|

Germany* |

1.16 |

1.16 |

1.18 |

1.21 |

1.23 |

1.33 |

1.49 |

1.43 |

1.48 |

1.61 |

2 |

|

|

Greece |

2.24 |

2.32 |

2.4 |

2.37 |

2.52 |

2.42 |

2.87 |

3.66 |

3.87 |

2.76 |

2.74 |

2.85 |

|

Hungary |

0.86 |

0.9 |

1 |

1.19 |

1 |

1.33 |

1.75 |

1.32 |

1.83 |

2.05 |

2.13 |

2.06 |

|

Italy |

1.13 |

1.06 |

1.17 |

1.19 |

1.22 |

1.17 |

1.58 |

1.52 |

1.5 |

1.47 |

1.5 |

2.01 |

|

Latvia* |

0.97 |

1.07 |

1.49 |

1.65 |

2.13 |

2.09 |

2.23 |

2.16 |

2.25 |

2.97 |

3.36 |

3.73 |

|

Lithuania* |

0.88 |

1.13 |

1.48 |

1.71 |

1.95 |

1.98 |

2.05 |

1.95 |

2.44 |

2.71 |

3.09 |

4 |

|

Luxembourg |

0.37 |

0.41 |

0.38 |

0.49 |

0.5 |

0.55 |

0.58 |

0.47 |

0.56 |

1.06 |

1.19 |

2 |

|

Montenegro |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.42 |

1.34 |

1.37 |

1.33 |

1.73 |

1.55 |

1.38 |

1.52 |

1.72 |

2.03 |

|

Netherlands |

1.12 |

1.1 |

1.13 |

1.12 |

1.19 |

1.29 |

1.37 |

1.32 |

1.39 |

1.6 |

2 |

2.49 |

|

North Macedonia |

1.09 |

1.05 |

0.97 |

0.89 |

0.94 |

1.16 |

1.24 |

1.45 |

1.58 |

1.68 |

1.89 |

2 |

|

Norway* |

1.54 |

1.58 |

1.73 |

1.71 |

1.72 |

1.84 |

1.97 |

1.68 |

1.46 |

1.82 |

2.27 |

3.35 |

|

Poland* |

1.86 |

2.21 |

1.99 |

1.88 |

2 |

1.96 |

2.21 |

2.19 |

2.21 |

3.27 |

3.79 |

4.48 |

|

Portugal |

1.31 |

1.33 |

1.27 |

1.24 |

1.34 |

1.37 |

1.43 |

1.52 |

1.39 |

1.33 |

1.58 |

2 |

|

Romania* |

1.35 |

1.45 |

1.43 |

1.73 |

1.79 |

1.83 |

2 |

1.85 |

1.75 |

1.6 |

2.17 |

2.28 |

|

Slovak Republic |

0.98 |

1.11 |

1.11 |

1.1 |

1.22 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

1.71 |

1.8 |

1.84 |

1.96 |

2.04 |

|

Slovenia |

0.98 |

0.94 |

1.02 |

0.99 |

1.02 |

1.06 |

1.07 |

1.24 |

1.3 |

1.32 |

1.37 |

2.02 |

|

Spain |

0.92 |

0.92 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.92 |

0.9 |

1 |

1.02 |

1.14 |

1.16 |

1.43 |

2 |

|

Sweden* |

1.07 |

1.02 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

1.04 |

1.1 |

1.43 |

1.48 |

1.68 |

2.31 |

2.51 |

|

Türkiye |

1.45 |

1.38 |

1.45 |

1.51 |

1.82 |

1.85 |

1.86 |

1.61 |

1.36 |

1.48 |

2.13 |

2.33 |

|

United Kingdom |

2.14 |

2.03 |

2.09 |

2.08 |

2.1 |

2.08 |

2.35 |

2.29 |

2.27 |

2.25 |

2.33 |

2.4 |

|

United States |

3.71 |

3.51 |

3.49 |

3.28 |

3.25 |

3.49 |

3.61 |

3.48 |

3.21 |

3.1 |

3.21 |

3.22 |

|

NATO Europe and Canada |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.41 |

1.45 |

1.48 |

1.51 |

1.69 |

1.63 |

1.63 |

1.74 |

1.99 |

2.27 |

|

NATO Total |

2.56 |

2.46 |

2.46 |

2.37 |

2.38 |

2.52 |

2.69 |

2.59 |

2.44 |

2.44 |

2.61 |

2.76 |

|

source: Nato |

||||||||||||

Nato national defence spending USD - millions

|

Country |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024e |

2025e |

|

Albania |

178 |

132 |

131 |

145 |

176 |

197 |

197 |

224 |

231 |

409 |

463 |

570 |

|

Belgium |

5200 |

4204 |

4258 |

4441 |

4845 |

4761 |

5324 |

6245 |

6904 |

7622 |

8548 |

13739 |

|

Bulgaria |

747 |

633 |

671 |

724 |

962 |

2159 |

1121 |

1276 |

1440 |

1992 |

2193 |

2389 |

|

Canada |

18172 |

18689 |

17708 |

23700 |

22399 |

22572 |

23330 |

25502 |

25898 |

28435 |

32334 |

43886 |

|

Croatia |

1078 |

892 |

837 |

917 |

952 |

986 |

983 |

1361 |

1285 |

1410 |

1731 |

2006 |

|

Czechia* |

1975 |

1921 |

1866 |

2259 |

2750 |

2982 |

3199 |

3915 |

3895 |

4538 |

7176 |

7223 |

|

Denmark* |

4057 |

3364 |

3593 |

3780 |

4559 |

4487 |

4886 |

5274 |

5473 |

8143 |

9631 |

14303 |

|

Estonia* |

514 |

463 |

497 |

541 |

615 |

637 |

719 |

749 |

820 |

1238 |

1424 |

1504 |

|

Finland |

3991 |

3401 |

3418 |

3536 |

3825 |

3900 |

4156 |

4145 |

4726 |

6266 |

7228 |

8587 |

|

France |

52022 |

43496 |

44209 |

46134 |

50507 |

49493 |

52519 |

56457 |

52238 |

59433 |

64469 |

66531 |

|

Germany* |

46176 |

39833 |

41606 |

45470 |

49772 |

52549 |

58652 |

62054 |

61405 |

73138 |

93747 |

|

|

Greece |

5234 |

4520 |

4637 |

4752 |

5388 |

5019 |

5492 |

8006 |

8488 |

6731 |

7075 |

7673 |

|

Hungary |

1210 |

1132 |

1289 |

1708 |

1615 |

2190 |

2767 |

2410 |

3270 |

4360 |

4736 |

4807 |

|

Italy |

24487 |

19576 |

22382 |

23902 |

25641 |

23559 |

30084 |

33140 |

31512 |

33856 |

35384 |

48800 |

|

Latvia* |

294 |

282 |

403 |

485 |

710 |

692 |

743 |

824 |

857 |

1254 |

1440 |

1653 |

|

Lithuania* |

428 |

471 |

636 |

817 |

1057 |

1094 |

1176 |

1308 |

1738 |

2165 |

2626 |

3607 |

|

Luxembourg |

253 |

250 |

236 |

326 |

356 |

381 |

426 |

403 |

461 |

642 |

783 |

1350 |

|

Montenegro |

69 |

57 |

62 |

65 |

75 |

74 |

83 |

91 |

86 |

114 |

138 |

174 |

|

Netherlands |

10349 |

8673 |

9112 |

9643 |

11172 |

12067 |

12838 |

13916 |

13899 |

16764 |

21858 |

28107 |

|

North Macedonia |

124 |

105 |

104 |

101 |

120 |

146 |

154 |

204 |

221 |

265 |

315 |

358 |

|

Norway* |

7722 |

6142 |

6431 |

6850 |

7544 |

7536 |

7228 |

8438 |

8694 |

8799 |

10792 |

16490 |

|

Poland* |

10107 |

10588 |

9397 |

9940 |

11857 |

11824 |

13363 |

15099 |

15338 |

26475 |

34454 |

44314 |

|

Portugal |

3007 |

2645 |

2616 |

2738 |

3249 |

3299 |

3273 |

3899 |

3578 |

3854 |

4849 |

6391 |

|

Romania* |

2695 |

2580 |

2646 |

3650 |

4363 |

4607 |

5056 |

5299 |

5197 |

5607 |

8312 |

9308 |

|

Slovak Republic |

999 |

987 |

1004 |

1056 |

1298 |

1802 |

2049 |

2066 |

2090 |

2445 |

2800 |

3094 |

|

Slovenia |

487 |

401 |

449 |

477 |

547 |

572 |

568 |

763 |

777 |

911 |

980 |

1513 |

|

Spain |

12634 |

11096 |

9975 |

11889 |

13200 |

12630 |

12828 |

14849 |

16451 |

18875 |

24555 |

35670 |

|

Sweden* |

6205 |

5103 |

5017 |

5229 |

5396 |

5560 |

5984 |

9071 |

8562 |

9849 |

13967 |

15207 |

|

Türkiye |

13597 |

11995 |

12642 |

12972 |

14486 |

14086 |

13339 |

12969 |

12291 |

16766 |

28274 |

32573 |

|

United Kingdom |

65692 |

59505 |

56362 |

55719 |

60380 |

59399 |

63500 |

71927 |

70846 |

76052 |

84169 |

90508 |

|

United States |

653942 |

641253 |

656059 |

642933 |

672255 |

750886 |

770650 |

824094 |

834977 |

858000 |

935000 |

980000 |

|

NATO Europe and Canada |

289314 |

254473 |

255594 |

275101 |

300474 |

301656 |

325896 |

358668 |

355382 |

418559 |

516453 |

607999 |

|

NATO Total |

943256 |

895726 |

911653 |

918034 |

972729 |

1052542 |

1096546 |

1182762 |

1190359 |

1276559 |

1451453 |

1587999 |

|

source: Nato |

||||||||||||

Features

The Age of Electricity is here -IEA

Electricity is becoming the most important source of energy, but the International Energy Agency warned that the world is entering a period of heightened energy insecurity marked by geopolitical volatility, rising demand, and an oil glut.

2016 set to be a turbulent year as civil unrest risk climbs across CEE and Central Asia

Civil unrest risks have risen sharply amid mounting political instability, simmering corruption allegations and inflation-linked discontent, according to Verisk Maplecroft.

Iraq identifies attackers behind Khor Mor gas field drone strike as Iran-backed militias

Iraq identifies militia elements behind 11th drone attack on Khor Mor gas field, with $7.41mn daily losses as authorities issue arrest warrants but decline to publicly name responsible group.

PANNIER: Who’s killing Chinese workers on the Afghan-Tajik frontier?

Beijing, among others, wants answers.