Is AI making us less intelligent? The debate over declining cognitive skills in the age of ChatGPT and smartphones

In 2008, The Atlantic ran a provocative cover story headlined, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” In the now-famous essay, technology writer Nicholas Carr argued that the internet was reshaping the way we think by reducing our capacity for deep thought, concentration, and long-form reading.

Fast-forward to 2025, and that early warning has resurfaced with renewed urgency as artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT and the ubiquitous use of smartphones raise fresh concerns about the erosion of human intelligence.

While AI has delivered countless benefits by transforming industries, democratising access to information, and automating mundane tasks, there is growing concern that it may also be contributing to cognitive decline in individuals and society at large.

The offloading of human thought

"Every time you use a calculator, you’re not using your brain to do basic arithmetic," says Dr Susan Greenfield, a British neuroscientist and author of Mind Change. “Now imagine that with every mental function—writing, searching, deciding—being offloaded to a machine. We’re at risk of becoming cognitively lazy.”

AI tools like ChatGPT have made it easier than ever to draft emails, summarise articles, write code, and even compose poetry. It may have been used in producing this piece – but will you ever know unless we tell you?

While undeniably useful, critics across the world, and especially so in Asia of late, argue that this convenience may come at a cost to critical thinking ability and ultimately the ability to write on their own. Ultimately, people may stop thinking for themselves.

The smartphone generation: a problem in progress

It’s not just AI that’s under scrutiny, however. The smartphone, in many ways the precursor to our AI-infused era, has long been associated with declining attention spans and reduced memory.

Research from the University of Texas at Austin in 2017 titled Cognitive Costs of Smartphone Presence – Journal of the Association for Consumer Research revealed that even the mere presence of a smartphone — face down and silent — can reduce working memory and problem-solving ability. Lead researcher Dr Adrian Ward noted that participants performed worse on cognitive tasks when their phones were within arm’s reach, as if the human brain is unconsciously offering up a portion of its active resources to the device.

By 2025, the average Briton checks their phone over 100 times a day, according to data from Ofcom. In Asia, it has been speculated that this number is even higher with teens constantly on their phones, and in some cases in Japan and South Korea in recent years, deaths occurring as people checking their phones accidentally step off train platforms or into oncoming traffic. Car drivers across Taiwan and throughout much of Southeast Asia also fit mobile phone holders to dashboards as a norm, offering convenience in access to route finding apps, but also another reason to remove the focus from the road ahead.

The phenomenon of “digital distraction” is now so widespread that some psychologists have likened it to addiction, drawing parallels with substance dependency.

Anecdotal evidence from educators paints a troubling picture. Teenagers across the world struggle to properly complete tasks in school, particularly those involving writing.

‘Google is your friend’ has long been a catchphrase for struggling students in schools and universities in some parts of Asia - especially so in the northeast of the continent in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Yet while a quick internet search may offer up a solution to an immediate problem, does it really help you learn? Is Google really a friend those in the classroom should be turning to?

IQ scores: a downward trend?

Adding to the debate is the controversial suggestion that IQ levels may actually be declining in some parts of the world. A 2018 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that IQ scores in Norway had been steadily falling since the 1970s, in the process reversing decades of gains known as the “Flynn Effect”.

Similar trends have been observed in France, Finland, Denmark, and Australia. Some researchers point to changes in education, diet, and social environment, oftentimes it appears looking for a scapegoat to avoid pinning the blame on smartphones and AI. But others, like Carr and Greenfield, believe the digital age may be playing a pivotal role.

“There is compelling evidence that we are externalising memory and reducing the frequency of complex mental tasks,” is a quote attributed to Dr Mark Williams, a cognitive neuroscientist at Macquarie University in Australia — according to ChatGPT. But is it accurate? A search found this claim to be unverifiable, but similar views were expressed in Dr Williams’ publications.

AI and the illusion of competence

Perhaps one of the most insidious effects of AI is what psychologists call the “illusion of competence” — the belief that one knows more than they actually do.

A 2024 study by Stanford University found that frequent users of AI writing tools were significantly more confident in their knowledge of subjects they had merely skimmed using summaries generated by AI. However, when tested on comprehension or critical analysis, their performance was lower than that of peers who studied original source materials according to a study cited in multiple outlets and covered in Stanford Human-Centered AI Reports.

“AI makes people feel smarter, but that’s a dangerous illusion,” warned lead researcher Dr Emily Zhao. “It’s like reading only the back cover of a novel and believing you’ve understood the plot.”

All of the above notwithstanding, the rise of AI and the pervasiveness of smartphones undoubtedly offer profound advantages. But the risk of cognitive decline is real if society becomes overly dependent on technology for basic intellectual functions.

As Nicholas Carr warned more than a decade ago, “What the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation.” In 2025, the same could be said of AI — and perhaps with even greater urgency.

Features

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Arm of state bags itself a crypto exchange

Following claims of money laundering, Icrypex becomes the latest of hundreds of companies to be seized by Turkish regime’s TMSF.

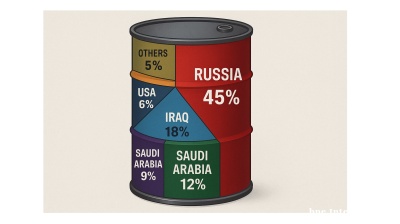

Kazakhstan reviews its big oil contracts looking for a better deal

COMMENT: Kazakhstan is reviewing its big oil contracts Kazakhstan has begun laying the groundwork for a revision of the contracts it signed with big oil in the 1990s when the country was flat on its back.

Can India dump Russian oil imports completely if Trump’s secondary sanctions appear?

Since early 2024 India has typically bought 1.5–2.0 mbpd of Russian crude, or about 35–40% of its total imports. US President Donald Trump is threatening crushing 100% tariffs on Russia’s business partners if they continue to import crude.

Indonesia targets rice fraud in multi-agency crackdown

At the heart of the probe are allegations that hundreds of rice brands, many operated by major producers, have been repackaging low-quality or subsidised rice and marketing it as premium-grade, often at inflated prices.