Hungary faces risk of severe economic instability if it does not get frozen EU funds, warns Oxford Economics

The Hungarian economy is being hit by a “perfect storm of shocks” and the “risks of a more severe scenario are rising”, Oxford Economics warned in a research paper on November 17.

Hungary is experiencing the highest inflation in the EU outside the Baltic States, the worst depreciating currency in the bloc, and the prospect of recession next year.

The country’s position is weaker than its Central European neighbours because of its high fiscal and external deficits, and its bigger foreign currency external debt load, all of which are contributing to the deteriorating sentiment towards the forint, which has lost 13% of its value so far this year.

“Hungary's swelling external imbalance – the current account deficit is wide (currently over 6% of GDP) – makes the economy especially vulnerable to this kind of shock. And Hungary's external debt denominated in US dollars and euros is higher than in its peers, meaning that currency depreciation hits it disproportionately,” Oxford Economics says.

The dire economic picture is a telling verdict on the economic model followed by Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s radical rightwing government over the past 12 years, and most recently the big boost to spending before this spring’s general election. Orban came to power in 2010 as a reaction to the 2007-9 global financial crisis but after some years of decent growth “Orbanomics” now looks like plunging the country back into crisis.

“If a number of catalysts – especially the cut-off of some EU funding – crystallise, Hungary could enter a period of macroeconomic instability not seen since 2008,” the consultancy said.

According to this crisis scenario, Oxford Economics predicts there would be a recession of 1.3% of GDP in 2023, GDP growth would remain weak into 2025, while inflation will not be back within the central bank’s target range before 2027. This could also force the bank to raise interest rates by a further 300 bps.

The government is anticipating a recession of 1-2% next year. The wiiw is predicting a 1.2% recession. The European Commission is currently predicting a 0.1% recession next year for Hungary, but said its forecast was "fraught with downside risks".

There is a strong risk of a hard landing if Hungary cannot get its hands soon on some €5.8bn of EU money in Recovery and Resilience (RRP) funds and €7.5bn from the Cohesion Fund, which have been frozen because of the Orban regime’s violations of the rule of law. The funds are crucial to investment financing.

Hungary has been given until November 19 to implement most of the remedial measures to address concerns over the misuse of EU funds. Unless it wins approval for the release of the RRP funds by the end of the year, it will lose 70% of them.

Following concessions by the government, there are now growing signals from Brussels that the Commission is getting ready to release at least some of the funding, which amounts to 6% of Hungarian GDP.

“Striking a deal with the EU and getting the macroeconomic policy mix right in the coming months will be critical to the economy's short-to-medium-term outlook," Oxford Economics says.

A final decision is expected on December 6. Yet even if the European Council approves the release of the RRF funds, they would still be disbursed via tranches linked to specific milestones to avoid a repeat of Hungary’s endemic backsliding.

“Securing EU money would be instrumental in limiting the chances of a severe downturn scenario materialising, as it would bolster the exchange rate and support capacity-enhancing investments. But even if the recent talks and signals of concessions coming from government officials warrant cautious optimism, this alone will not negate a (very) hard landing scenario completely,” warns Oxford Economics.

Inflation hit 20.1% in September and Oxford Economics warns that there is now a risk of inflationary expections “fully deanchoring” in a wage-price inflation spiral, hitting asset prices and amplifying economic instability. The consultancy points out that in September inflation grew more month-on-month (4.5%) than the central bank’s target for annual inflation (3%).

Inflation has been largely driven by the depreciating forint and rises in energy prices as the government scales back its hugely expensive caps on prices. But Oxford Economics says that domestic demand factors such as the tight labour market and spending from accumulated savings are also pushing core inflation. This remains elevated despite big rises in central bank interest rates, which have now hit 13%, with the one-day deposit rate at 18%.

The external deficit has also been propelled by both rising fuel bills and overheated domestic domand. The deficit grew to around 6.2% of GDP in August and is expected to deteriorate further, likely surpassing 8% of GDP in 2023, substantially above its CEE peers (Poland 4.3%, Czechia 6.8% of GDP), then narrowing only gradually, the consultancy forecasts.

Hungary is still burdened by elevated external debt. In Q2 2022, debt was equal to 82% of GDP, well above Czechia (around 30%), Poland (51%) and Romania (46%). Three quarters of the external debt (some 62% of GDP) is also in hard foreign currencies, worsening the vulnerability of household and company debtors to the depreciating exchange rate.

Oxford Economics says that, given the already high interest rates, the central bank should continue to focus on alternative tools, and most of the heavy lifting should be done by fiscal policy. “Much more will need to be done especially on the fiscal side to avoid permanent damage to the economy,” it says.

“Despite a push to cut some expenditures (mostly on the investment side), the fiscal deficit is likely to surpass 5% of GDP this year, with little improvement seen in 2023, not least due to high import gas prices locked-in in the latest bilateral deal with [Russian gas giant] Gazprom.

"The situation is being worsened by the fact that the Hungarian government has excessively subsidised retail energy. And while withdrawing all remaining support at once is likely politically unfeasible due to the high social cost, at the very least Orban's government needs to provide a clear path for fiscal tightening, and then follow through on it,” it says.

Opinion

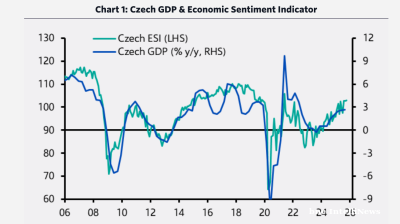

COMMENT: Czechia economy powering ahead, Hungary’s economy stalls

Early third-quarter GDP figures from Central Europe point to a growing divergence between the region’s two largest economies outside Poland, with Czechia accelerating its recovery while Hungary continues to struggle.

COMMENT: EU's LNG import ban won’t break Russia, but it will render the sector’s further growth fiendishly hard

The European Union’s nineteenth sanctions package against Russia marks a pivotal escalation in the bloc’s energy strategy, which will impose a comprehensive ban on Russian LNG imports beginning January 1, 2027.

Western Balkan countries become emerging players in Europe’s defence efforts

The Western Balkans could play an increasingly important role in strengthening Europe’s security architecture, says a new report from the Carnegie Europe think-tank.

COMMENT: Sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil are symbolic and won’t stop its oil exports

The Trump administration’s sanctions on Russian oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil, announced on October 22, may appear decisive at first glance, but they are not going to make a material difference to Russia’s export of oil, says Sergey Vakulenko.