On March 1 2025, production at PT Sri Rejeki Isman Tbk, widely known as Sritex, came to a complete halt.

Once celebrated as Southeast Asia’s largest textile producer, the Indonesian firm shuttered its operations, resulting in job losses for nearly 11,000 workers across Central Java. The closure sent tremors through the nation’s economy and prompted serious concerns over the future of Indonesia’s textile industry.

From market stall to manufacturing empire

Founded in 1966 by H.M. Lukminto as a modest cloth kiosk in Solo’s Klewer Market, the company gradually expanded its operations. According to the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, a fabric printing facility followed in 1968, and by 1978, Sritex had officially incorporated. It eventually became a vertically integrated manufacturer, managing processes from yarn spinning to finished garments. Sritex reached its peak by supplying military attire to over 15 countries and producing garments for major global retailers such as H&M and Uniqlo.

The company symbolised national pride and was a significant contributor to Indonesia’s export economy. In 2020 alone, it posted sales nearing $1.3bn, including $762mn from exports. However, despite these figures, cracks in the foundation were beginning to show.

Political optimism

In early 2024, signs of hope lingered, however. Detik reports that Gibran Rakabuming Raka, son of President Joko Widodo and then a vice-presidential contender, paid a visit to Sritex’s Sukoharjo facility alongside his wife, Selvi Ananda. The visit sparked excitement, with thousands of employees chanting campaign slogans and brandishing signs in support.

The company’s President Commissioner, Iwan Setiawan Lukminto, also the founder’s son, expressed optimism that Gibran’s political journey could boost the beleaguered textile sector. As a symbolic act, Iwan gifted him a tactical jacket made by Sritex, underlining the firm’s dual commercial and military production capabilities.

Gradual decline

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic proved catastrophic for Sritex though. Global demand for textiles plunged, severely impacting revenues. Although the firm sought to restructure its debt in 2021, financial conditions continued to deteriorate.

By October 2024, the Semarang Commercial Court had ruled the company insolvent after creditors turned down its proposed restructuring plan. The South China Morning Post reports that the Supreme Court later affirmed this decision in December 2024. In the months that followed, production facilities in Sukoharjo, Boyolali, and Semarang slowly closed. By March 2025, operations had ceased entirely.

The shutdown devastated thousands of employees, many of whom had worked at Sritex for years. It also had a domino effect on the local economy, impacting countless small suppliers and businesses linked to the firm.

Scandal and mismanagement

The company’s troubles were further complicated by a major corruption case. In May 2025, Antara reports that former President Director Iwan Setiawan Lukminto was taken into custody, along with two banking officials from Bank BJB and Bank DKI. They faced corruption charges concerning the unlawful approval of loans totalling IDR692bn (around $44bn), even as the company’s finances were clearly in decline.

Authorities found that the loans were granted without appropriate risk evaluation, violating banking norms and leading to significant financial losses for the state. These revelations pointed to critical shortcomings in both internal corporate practices and external regulatory mechanisms.

A closer examination of Sritex’s finances showed disturbing shifts: from reporting a profit of $85.32mn in 2020 to a staggering $1.08bn loss the following year - figures that suggest deep-rooted financial irregularities.

Investigations continue

As of June 2025, the corruption probe had widened. According to Antara, Prosecutors are now examining additional senior figures suspected of being involved in the irregular lending. Both banks implicated are under regulatory scrutiny and could face penalties for their role. The Attorney General’s Office has committed to holding all parties accountable and recovering state funds.

Simultaneously, former employees and trade unions are demanding fair compensation and clearer communication. Public sentiment is pushing for stronger enforcement of anti-corruption laws and greater transparency in the corporate sector.

Wider impact

Sritex’s downfall is not an isolated event. According to the Confederation of Nusantara Trade Unions (KSPI), between 2019 and mid-2024, at least 36 textile companies in Indonesia shut down, reflecting a sector plagued by high operational costs, intensified global competition, and poor financial management.

Amid the turmoil, industry stakeholders are also urging regulatory reform. The Indonesian Textile Association (API) has called on the Ministry of Trade to revise Permendag No. 8/2024 and reinstate technical considerations (pertek) to tighten import oversight. API argues the regulation weakened domestic protections and, along with a surge in illegal imports, accelerated industry decline - a concern echoed by Sritex’s leadership.

As the government reviews the policy, discussions have focused on striking a balance between safeguarding local manufacturers and streamlining import procedures.

In response, President Prabowo Subianto’s administration has pledged to support the affected workforce. Initiatives include severance pay assistance, retraining schemes, and efforts to attract investors who might revive Sritex’s facilities and equipment.

Nonetheless, many industry observers argue that only substantial reforms in industrial policy, financial governance, and corporate accountability can prevent such implosions in the future.

What happened in Sritex is more than just corporate collapse, it’s a warning about what happens when unchecked growth outpaces good governance. The signs were there: erratic financials, dubious loans, and a reliance on political theatre over real reform.

But the real cost was borne by nearly 11,000 workers, many of whom lost their livelihoods overnight. These weren’t just employees — they were the backbone of communities now struggling to stay afloat. It’s a stark reminder of how fragile job security has become, particularly in labour-heavy sectors like textiles.

While government promises of severance and retraining are welcome, they’re no substitute for a long-term plan. Protecting workers should be baked into industrial policy, not patched in after the damage is done.

Features

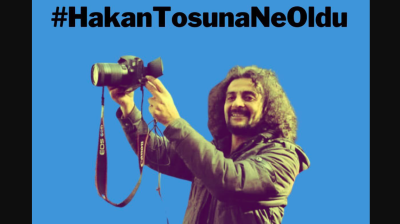

Journalist beaten to death in Istanbul as security conditions in Turkey rapidly deteriorate

Publisher, meanwhile, is shot in leg. Reporters regularly experience violence, judicial harassment and media lynching.

Agentic AI becomes South Korea’s next big tech battleground

As countries race to define their roles in the AI era, South Korea's tech giants are now embracing “agentic AI”, a next-generation form of AI that acts autonomously to complete goals, not just respond to commands.

Iran's capital Tehran showcases new "Virgin Mary" Metro station

Tehran's new Maryam metro station honours Virgin Mary with architecture blending Armenian and Iranian design elements in new push by Islamic Republic

Indonesia’s $80bn giant seawall

Indonesia’s ambition to build a colossal seawall along the northern coastline of Java has ignited both hope and heated debate. Valued at around $80bn, the project aims to safeguard the island’s coastal cities from tidal floods and erosion.