Russia is so big that the Kremlin can’t protect all its pipelines and refineries. Since August the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) has mounted a continuous barrage of drone and missile attacks on Russian refineries that have reduced Russia’s oil product production by about 20% at the last count and sparked a fuel crisis. As Kyiv rolls out a new generation of missiles such as the Flamingo cruise missile and its increasingly effective long-range drones, this will only get worse.

The Druzhba oil pipeline — the Soviet-era key export route to Europe — has been rendered “practically dead in the water” due to repeated attacks in August that led to a war of words between Budapest and Brussels, which is demanding it pressure Kyiv to halt its repeated missile strikes. The major oil terminal Ust-Luga in the Baltic Sea has also been hit and badly damaged in the last few weeks.

Attention is now turning to Russia’s major natural gas conduits, including the Northern Lights and Yamal-Europe pipelines, which run from the Yamal Peninsula and the Urengoy gas fields through Belarus and Poland to Germany and Ukraine. The Nord Stream pipelines were already destroyed by explosions in September 2022 and Poland suspended its section of the Yamal pipeline following Russia’s full-scale invasion, but there are still several pipelines delivering Russian gas to Central Europe. All-in-all Russian gas deliveries still made up 15% of the EU’s gas supplies in 2024, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), and currently can’t be replaced, despite a plan to reduce Russian gas imports to zero by 2027.

These natural gas pipelines are the lifeline of substantial parts of the Russian economy, which has been turned into a war economy. It is therefore a military target. Russia simply doesn’t have enough air defence systems to protect all its oil and gas assets. 70% of its air defence systems have been deployed to the Ukrainian theatre and those that remain in Russia are used to protect the government buildings in Moscow and key military installations or weapons factories. There are not enough to protect every pipeline or oil refinery in the country.

The Yamal system alone stretches more than 5,000km and includes dozens of pumping stations and hubs, including key branches to Vyborg and Ust-Luga. Ukrainian officials suggest it is “only a question of time” before these routes come under attack, as Ukraine’s long-range strike capability expands.

The introduction of Ukrainian long-range missiles has changed the rules of the game. For most of the last three years the West has prevented the AFU from using what missiles it had to attack targets inside Russia’s territory as part of its “some, but not enough” escalation management policy. Now that Ukraine is increasingly producing its own long-range drones and missiles that don’t have any restrictions on their use or targets, those rules no longer apply. Russia’s large size, which in the past was an advantage, has turned into a liability, say analysts. Economic lifelines can be cut at multiple points and with devastating effects and there is little the Kremlin can do about it.

The Russian economy remains heavily dependent on energy exports, with limited diversification since 2014. Russia exported $192bn worth of oil and LNG last year, according to the IEA, and the unspoken embarrassing detail is that the EU is amongst its major customers. France imported a record amount of LNG in July sending $600mn to Moscow as payment. The EU sends far more money to Russia to pay for fuel than it sends to Ukraine to keep it in the war.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy has complained constantly about the double standard and called on the EU to tighten energy sanctions, but as Europe remains hooked on Russian oil and gas little has been done; some 20% of Russia’s so-called shadow fleet is made up of EU tankers, mostly Greek, that are simply legally profiteering from the war as long as they meet the letter of the oil price cap sanctions rules. The eighteenth sanctions package tightened sanctions on the shadow fleet, introducing a floating rate oil price sanctions cap of 15% below market rates for the Urals blend, Russia’s main export product, that is designed to cut Russia off from using Greek tankers, but the tankers owners told Financial Times they were sure they could find a workaround. The nineteenth sanctions package, currently under discussion, will not target energy, says Brussels.

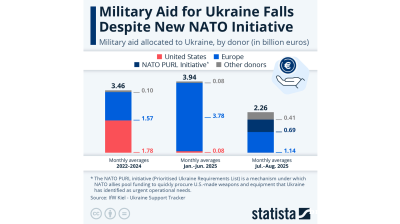

Ukraine argues that targeting oil and gas infrastructure — including storage depots, refineries and port terminals — is a strategic means to degrade Moscow’s ability to finance and sustain the war. The West remains scared of distributing supplies and spending prices spiking. Kyiv doesn’t care anymore what happens to the global oil markets and with the Trump administration ending all aid to Ukraine and the EU unable to replace it, Bankova (Ukraine’s equivalent of the Kremlin) has escalated its attacks on Russia's oil infrastructure.

“Russia has only three major ports where oil can be loaded fast and those are Ust-Luga, Novorossiysk and Tuapse. If those are taken out, then Russia can neither make money nor supply its (war) economy,” German military blogger Tendar noted in a social media post. “Targeting Russia's energy infrastructure is the most efficient way to lead Russia's economy into its downfall, and by extension the war.”

Opinion

COMMENT: Hungary’s investment slump shows signs of bottoming, but EU tensions still cast a long shadow

Hungary’s economy has fallen behind its Central European peers in recent years, and the root of this underperformance lies in a sharp and protracted collapse in investment. But a possible change of government next year could change things.

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.

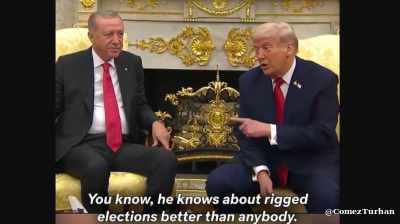

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Consumed by the Donald Trump Gaza Show? You’d do well to remember the Erdogan Episode

Nature of Turkey-US relations has become transparent under an American president who doesn’t deign to care what people think.