There’s no shortage of hype when it comes to the immense profits to be made from supplying the rare earths required by the world’s energy, tech and defence transitions and Kazakhstan is intent on claiming a big piece of the pie. But can the realities on, or rather, in, the ground match its ambitions?

In April, the Central Asian country’s industry and construction ministry suggested that Kazakhstan may be home to the globe’s third largest deposit of rare earth elements (REEs) by total reserves. The Zhana Kazakhstan site, part of the larger Kuyrektykol area, was estimated to hold 20mn tonnes of rare earth ore, with an average grade of approximately 700 grams per tonne. That amounts to around 935,400 tonnes of recoverable rare earth oxides (REO).

If the extent of the resources, located approximately 420 kilometres (261 miles) from the capital Astana, is confirmed, Kazakhstan will rank just behind China and Brazil for rare earth reserves.

Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has talked of the REEs boasted by Central Asia’s largest economy as the “new oil”. Explorers and potential buyers—and there is no shortage of those—sense a strategic opportunity. Local experts warn, however, that all of this remains provisional. To get hugely excited would be premature.

“To call it a deposit, you first need to fully study all the elements,” said Georgiy Freiman, head of the Professional Association of Independent Mining Experts, speaking to Euronews. He cited the need for comprehensive hydrogeological and geomechanical studies and internationally recognised feasibility assessments such as NI 43-101 or that of the Australasian Joint Ore Reserves Committee (JORC).

No public drilling results or classified reserves for Zhana Kazakhstan have yet been released.

“You need to study hydrogeology, geomechanics, as well as assess the feasibility of extraction and in what form they [the rare earths] can be extracted. You need to conduct an economic assessment, taking into account the market situation, the needs of relevant industries,” Freiman added.

“Only when all these factors are analysed, and an economic model is developed can it truly be called a deposit. Without that, it remains mere speculation,” he added.

As things stand, there's no sign of Kazakhstan among the rare earth "powers". Those working at the Zhana Kazakhstan site hope that will soon change.

Maxim Klochkov, chief geologist of the company that discovered the Zhana Kazakhstan site, Tsemtrgeolsiemka, told Sputnik Kazakhstan: “This is not a deposit. It’s a prospective area with only forecast resources… A deposit is an economically justified site with calculated reserves… Everything else is just an area or occurrence.”

Host-rock

In all, the Kazakh government has reported 124 identified REE sites, with 37 already explored. Challenges that must be addressed with such sites include potential thorium content and difficult host-rock conditions that can complicate extraction.

Important to note is that Kazakhstan currently has no REE refining infrastructure. All of its present rare earth output is exported to refiners in China, which is far ahead of anywhere else in the world for both confirmed REE deposits and rare earth refining knowhow and machinery.

Industry analysts estimate that building Kazakh rare earth refining capabilities would require over $3bn in investment. What’s more, the Zhana Kazakhstan site’s development could take six to 12 years and involve extensive geological, environmental and commercial studies.

Arthur Polyakov of the Minex Forum observed how Kazakhstan lacks deep-processing technology for REEs and will need foreign partnerships, notably with Chinese processors and EU firms focused on green technology.

“Currently, Kazakhstan lacks the necessary technologies for deep processing of rare earth elements, so it will require support from foreign partners,” Polyakov told Euronews.

Foreign support could come at the cost of Kazakhstan losing control over its own assets, especially with Russia and China vying for influence in Central Asia.

The Times of Central Asia quoted Kazakh financial analyst Rasul Rysmambetov as warning that major international players, particularly from Russia, may seek to dominate Kazakhstan’s rare-earth sector.

“Several large Russian companies [involved in the field] already operate in Kazakhstan. It is crucial to ensure that control over these resources remains in the hands of the state,” Rysmambetov was quoted as saying.

“We can expect attempts by foreign firms, particularly Russian and Chinese companies, to acquire major Kazakh mining assets. The US is unlikely to compete directly, but its companies may be indirectly involved,” he added.

Careful manoeuvring between the various interested parties can only complicate and slow down the process of jumpstarting the ex-Soviet state's bit to reach its REE goals.

Routes out of Kazakhstan

For export trade in general, officials are already developing transit infrastructure and logistics that could potentially support the country’s REE consignments. Kazakhstan is investing in the Middle Corridor – the trans-Caspian East-West trade route running south of Russia that links China and Europe – as well as the Caspian Sea port of Aktau.

The port already handles uranium shipments and its facilities could be adapted to process REE cargo. Still, the route has a long way to go before it can be considered reliable for such shipments.

Grant Isaac, vice president of Canadian miner Cameco, reportedly told a teleconference with investors that, where Kazakh uranium is concerned, the export route has proven less reliable and predictable than traditional corridors offered via Russian railways.

The multimodal Middle Corridor, or Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), comprises of a rail journey across Kazakhstan, a ferry trip across the Caspian Sea, a rail trip across Azerbaijan and Georgia and a Black Sea ship or rail passage from Georgia to Turkey (or alternatively a Black Sea voyage direct to a European coast). Each stage can introduce substantial delays. A transit can stretch to from 40 to 60 days. Opt for the route through Russia, and the dispatcher is looking at 18–23 days.

A World Bank analysis found that the Middle Corridor, or MC, struggles with insufficient multimodal infrastructure—its port, railway and ship capacities are underdeveloped, causing significant delays at border crossings and in port transits.

“A combination of short-term gains in efficiency through better coordination, logistics, and digitalization with medium-term investments are needed to improve the corridor's attractiveness,” the World Bank noted.

"The MC will require large investments over the next 10 years, which have largely been identified and agreed by the [relevant] countries (signed Roadmap in November 2022), but in the short term, massive efficiency improvements can be achieved through better coordination, logistics, and digitalization, among other measures," the study added.

As such, the effectiveness of Kazakhstan’s REE export potential will likely be tied to improvements in the Middle Corridor’s efficiency, which could take up to at least another 10 years to deliver, according to the study.

The conclusion has to be that in terms of the actual extent of minable REE reserves in Kazakhstan, the practicality of establishing sufficient domestic rare earth refining operations and the possibilities in arranging smooth and efficient export for the processed product, hold your horses.

Features

South Korea, the US come together on nuclear deals

South Korean and US companies have signed agreements to advance nuclear energy projects, aiming to meet rising data centre power demands, support AI growth, and strengthen the US nuclear fuel supply chain.

World Bank seems to be having second thoughts about Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam

Ball now in Dushanbe’s court to justify high cost.

INTERVIEW: From cinema to Serbian police cell in one unlucky “take”

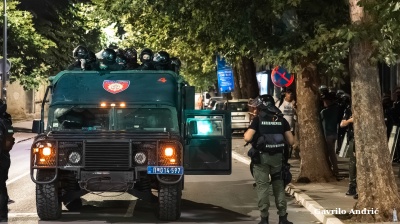

An Italian software engineer caught in Belgrade’s August protests recounts a night of mistaken arrest and police violence in the city’s tense political climate.

_Cropped_1756210594.jpg)

Turkey breaks ground on its section of the TRIPP rail corridor

Turkish project would help make TRIPP the go-to route for Middle Corridor freight.