Slovenia has become one of the latest EU member states to legalise cannabis for medical purposes, while also taking its first steps towards allowing limited personal use. The shift, seen by many as a landmark in public health and civil rights, has already sparked heated debate. Supporters hail it as long overdue reform, while employer organisations warn of serious risks for workplace safety, liability and public trust.

The debate reflects a tension familiar across Europe: how to balance personal freedoms and therapeutic benefits with concerns over occupational safety, regulation, and the protection of children and adolescents.

From referendum to reform

The immediate push for reform stems from last year’s consultative referendum in Slovenia, in which a majority of Slovenians backed use of cannabis for medical purposes and personal use under strict conditions. Acting on this mandate, the ruling coalition parties submitted a proposal for a Cannabis Act on limited personal use.

However, the health ministry stressed the government’s cautious approach regarding the use of cannabis for personal use.

"Its implementation requires strict adherence to preventive measures for the protection of children and adolescents,” the ministry’s press office said in a statement to bne IntelliNews.

The new draft followed the adoption in July of the Cannabis for Medical and Scientific Purposes Act, a separate law that gave doctors the authority to prescribe cannabis for any condition based on professional judgement. Prescriptions are capped at one month of treatment, non-renewable, and subject to both an initial and follow-up medical exam.

MP Sara Zibrat from the ruling Freedom Movement hailed the law as “revolutionary” for both patients and the economy. By avoiding monopolies and streamlining licensing, she argued, Slovenia could build a fairer, more accessible system than in many other EU countries. Separate permits for production, trade and scientific use will be issued under close supervision, with licences lasting 15 years and renewable thereafter.

Until now, Slovenia’s approach was far more restrictive. Since 2017, cannabis was recognised as having potential therapeutic uses but was available only on special prescription. All products were imported, as domestic production lacked a legal framework. The new law remedies both problems, allowing state-supervised cultivation by licensed pharmaceutical companies while continuing to prohibit home growing by private individuals.

Personal limits

While hard drugs are not widely used in Slovenia and other Yugoslav countries, marijuana use has long been relatively common, so to a large extent the draft Cannabis Act would legalise an existing phenomenon.

The act would allow adults residing in Slovenia to cultivate up to four cannabis plants per person for personal use and possess up to 150 grams of dried cannabis at their residence. In public areas, individuals may carry up to seven grams of dried cannabis and five grams or five millilitres of cannabis resin, extracts or other preparations.

Households with multiple adults may possess up to 100 grams or millilitres of resin and related preparations collectively, with a maximum of six plants if several individuals cultivate together.

The bill also sets strict measures to prevent access by minors, prohibits smoking near children and educational institutions, while it allows limited free distribution of cannabis among adults. It establishes THC limits for drivers, with penalties ranging from €300 to €1,200 depending on blood THC content, and forbids employers from testing THC in regular employee health checks.

The aim of the legislation is to provide access to tested, safe cannabis for personal use while reducing illegal production and trafficking of unregulated cannabis products.

Employer opposition

However, employer associations opposed the draft law on limited personal cannabis use, warning of negative effects on the workplace.

Leading employer associations including the Chamber of Commerce of Slovenia, the Chamber of Crafts and Entrepreneurs, the Association of Employers of Slovenia and the Association of Employers in Craft and Small Business of Slovenia (ZDOPS) issued a joint statement demanding its withdrawal.

They argue the law would “make it impossible to ensure a safe working environment and cause numerous new risks for individuals, society and companies”.

In a statement sent to bne IntelliNews, ZDOPS stressed that the bill contradicts the fundamental principles of occupational health and safety. “The draft law would directly threaten a safe working environment and cause numerous new risks for the health of employees and the safety of society as a whole,” the association warned.

“According to the proposed law, the presence of THC in the body should not be determined as part of regular health examinations of workers, which are used to check risks to occupational health and safety … This prevents timely recognition of reduced psychophysical abilities of workers.”

A central concern is the monitoring of THC levels in the workplace. The draft law blocks testing during routine medical checks, something employers see as a red flag. High-risk jobs such as pilots, doctors, paramedics, heavy machinery operators and security guards require zero tolerance for impairment, they insist.

Beyond safety, employers point to legal uncertainty. Who would bear responsibility if an accident occurred under the influence of cannabis? Would health funds, pension funds or companies themselves shoulder the burden of sick leave and compensation?

Their statement concluded bluntly: "The right to a safe work and social environment is much more important than the right to use cannabis. We expect that the government will give a negative opinion on the bill and propose its withdrawal from the legislative procedure."

Balancing freedoms with safeguards

The Ministry of Health, however, framed the issue differently. A spokesperson said in a written statement to bne IntelliNews that the draft law on personal use was submitted by MPs in line with the referendum result, but underlined the need for strong safeguards.

“Its implementation requires strict adherence to preventive measures for the protection of children and adolescents, including educational programmes, information, awareness-raising and early interventions to prevent potential risks,” the ministry said.

“It is equally important that these measures are closely linked to health and social services in order to ensure a comprehensive approach to the protection and safeguarding of children and adolescents.”

Officials argue that cannabis reform cannot succeed without a broader public health strategy that reduces risks and protects vulnerable groups.

Europe legalises

Slovenia’s move reflects broader European trends. Medical cannabis is now legal in more than 20 EU member states, though regulations differ widely. Four years ago, Malta became the first EU country to legalise recreational cannabis, allowing adults over 18 to carry up to 7 grams, keep up to 50 grams at home. Germany introduced partial legalisation of recreational cannabis in April 2024, permitting adults to carry up to 25 grams in public and store up to 50 grams at home.

Another EU country, Slovenia’s neighbour Croatia, legalised cannabis for medical use in 2015.

In the Western Balkan region, North Macedonia became the first country to legalise medical cannabis in early 2016 and later moved towards permitting recreational use. The full legalisation was still under debate as of late 2020.

Slovenia’s cautious approach – starting with medical use, followed by a tightly debated personal use bill – reflects both the momentum of reform and the depth of resistance. The issue pits individual freedoms against occupational and public health concerns, raising questions about how far Slovenia is ready to go.

The cannabis debate comes at a politically sensitive time for Prime Minister Robert Golob’s coalition, which has faced criticism over reforms in health, housing and energy. The Freedom Movement and coalition partner Levica (The Left) see cannabis reform as part of a progressive agenda. But the strong opposition from employers and centre-right parties could complicate its path through parliament.

The July vote on the medical law revealed these divisions clearly: 50 MPs voted in favour, 29 against. While the coalition has the numbers to push reforms through, it risks fuelling polarisation and potential backlash if the personal use bill is not carefully crafted.

For now, Slovenia has taken a historic step in recognising cannabis as a legitimate part of medical treatment. The personal use debate, however, remains unresolved. Employers have drawn a clear red line on workplace safety, while the Ministry of Health emphasises prevention, education and child protection.

Features

Indian bank deposits to grow steadily in FY26 amid liquidity boost

Deposit growth at Indian banks is projected to remain adequate in FY2025-26, supported by an improved liquidity environment and regulatory measures that are expected to sustain credit expansion of 11–12%

What Central Asia wants out of the upcoming Washington summit

Clarity on critical minerals and a lot else.

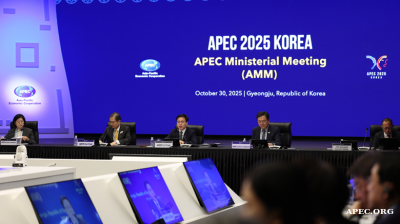

Global leaders gather in Gyeongju to shape APEC cooperation

Global leaders are arriving in Gyeongju, the cultural hub of North Gyeongsang Province, as South Korea hosts the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. Delegates from 21 member economies are expected to discuss trade, technology and security.

Project Matador marks new South Korea-US nuclear collaboration

Fermi America, a private energy developer in the United States, is moving ahead with what could become one of the most significant privately financed clean energy projects globally.