As the ongoing hostilities between Iran and Israel threaten to escalate into a broader regional war, much of the world is bracing for the implications. While the Middle East will, of course, bear the immediate consequences of any intensified conflict, the reverberations are already being felt far beyond. In East and Southeast Asia - a region often, but mistakably perceived as geopolitically removed from the Middle East - the fallout of a full-blown Iran-Israel war could be both significant and multifaceted.

From energy security and trade disruptions to political polarisation and rising tensions among Muslim-majority nations such as Indonesia - the world’s most populous Muslim country - Malaysia, and Pakistan, the consequences for Asia could reshape regional dynamics and test long-standing diplomatic balances.

Energy shock: Asia’s Achilles’ heel

East and Southeast Asia are heavily dependent on imported energy, with much of their oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) supplies originating from or transiting through the Middle East. An all-out conflict between Iran and Israel would almost certainly jeopardise shipping through the Strait of Hormuz. That some sources already have Iran as pondering whether or not to mine the narrow waterway is worrying.

Iran has previously threatened to close the Strait should it come under attack from Israel or its allies in a demonstration of Tehran’s awareness but disregard for the power needs of the Western world. As such, by doing so, overnight Tehran would only reinforce the belief of many in the West and Asia east of Tehran, that Iran is more apt to adopt extremist measures than anything bordering on the sensible.

Even limited skirmishes have, in the past, spooked markets and driven up oil prices. This time, a sustained military conflict, however, could cause prices to surge to levels not seen since the Gulf War or the 1973/74 oil embargo.

For Asian economies, the implications would be profound. Japan, South Korea, China, and India all rely heavily on energy imports from the Gulf. Even Southeast Asian nations that are net exporters of oil, such as Malaysia and Brunei, are not immune as rising prices could potentially help stoke inflation and disrupt supply chains

The LNG market is especially vulnerable. In recent years, countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Thailand have become increasingly reliant on spot LNG cargoes, many of which originate from Qatar. Vietnam is also adding to its power production capacity by turning to LNG. These shipments pass through waters that could become militarised in a wider Iran-Israel conflict.

Nations with more robust strategic reserves, such as China and Japan, perhaps even South Korea may weather short-term shocks, but prolonged instability would test even their resilience.

Pakistan’s dilemma

Should the Iran-Israel war escalate into a broader confrontation involving the United States or Saudi Arabia, Pakistan could find itself walking an increasingly treacherous tightrope.

Islamabad has long maintained a delicate balance between its historical ties with Saudi Arabia and its neighbourly relations with Iran. While Iran shares a long, and very porous border with Pakistan, and many Pakistani Shias look to Iran for religious leadership, the country also hosts significant Sunni hardline groups, many of whom are staunchly anti-Iranian.

Should the opportunity arise, it is not impossible that Sunni groups could work with others to destabilise Iran through the back door. Whilst far from the headlines at present the ongoing insurgency by Baloch separatist insurgents and various Islamist militant groups against the government of Iran could prove critical should the regime in Tehran be seriously challenged.

That there are now almost 5mn ethnic Balochs in Iran will cause some consternation in Tehran.

Politically too Pakistan has often leaned closer to the Gulf states but popular sentiment among the urban middle class and religious political parties could swing in favour of Iran if the war is seen through the prism of an anti-Zionist or anti-Western struggle.

This may come to a head if Israel directly targets religious sites.

The risk of militant spillover is also real. Pakistan has struggled for years with sectarian violence, and an Iran-Israel conflict risks fuelling both Sunni and Shia radicalisation and as a result the government may come under growing pressure to crack down on either pro-Iranian or anti-Iranian groups, potentially triggering new cycles of domestic unrest.

The first cracks have already appeared in the long-held belief that Iran and Pakistan are ‘tight’ with Islamabad in the past 24-hours rejecting a claim by a senior Iranian general that Pakistan would use nuclear weapons against aggressors should Iran be hit.

The rejection came in the form of a post on X on June 16 by Pakistan's Defence Minister Khawaja Muhammad Asif, who said that Islamabad hads made “no such commitment” to Tehran.

Islamic solidarity

Southeast Asia is home to two of the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nations: Indonesia and Malaysia. Both have historically championed the Palestinian cause and taken strong rhetorical stances against Israel. While neither recognises the Israeli state, they have maintained unofficial channels of communication over the years with Jerusalem, primarily for trade and humanitarian concerns.

The escalation of the Iran-Israel conflict may, however, force both Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta into a more defined position. If Iran succeeds in framing the war as a continuation of Israel’s aggression against Muslims globally, a stretch at best, popular opinion in Indonesia and Malaysia could become far more vocally pro-Iran. Whether this would see the political elite in either nation react though is unlikely.

In recent weeks, mass rallies in Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur have already expressed support for Palestinians and denounced Western military aid to Israel. Should Iranian cities come under Israeli bombardment, it is not inconceivable that such protests will extend their support to Tehran.

This will remain largely rhetorical, however, and even if civil groups, Islamic organisations, and even political elements begin openly calling for stronger government support for Iran there is little to no real chance that either country would ever become involved militarily.

More broadly, the war could challenge ASEAN unity on matters of foreign policy though. Countries such as Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam with their closer economic and military ties to the United States and Israel may resist any regional attempts to issue condemnations or take sides. In contrast, Indonesia and Malaysia may seek stronger Muslim solidarity, including joint statements, boycotts, or diplomatic moves that target Israeli interests in the region but little more.

East Asian giants: China and Japan

In East Asia meanwhile, the calculus is equally complex. China maintains cordial relations with both Iran and Israel, with significant economic and military ties to each. It has invested heavily in Iranian infrastructure projects and remains a top buyer of Iranian oil. At the same time, Israel is a vital partner in tech and innovation, areas central to Beijing’s own ambitions in the South China Sea and potentially against Taiwan.

China is already pushing for a diplomatic resolution, positioning itself as a potential mediator in a similar form to its role in brokering peace between Saudi Arabia and Iran in 2023.

A prolonged war would also damage China’s Belt and Road interests in the region, particularly if infrastructure in Iran is targeted. Beyond this, China is likely limited in its real interest in the ongoing hostilities.

For Japan and South Korea, the concern is more immediate and pragmatic. Both nations are energy importers with few natural resources of their own. Any disruption in Gulf oil and LNG flows in particular would be a national security concern. Japan has traditionally stayed out of Middle Eastern entanglements, but may be forced to take a more vocal stance under pressure from the US.

South Korea, too, could find itself in a delicate position. While reliant on the US security umbrella, Seoul has economic reasons to remain neutral.

Risks to regional stability

Beyond state-level implications, the Iran-Israel war could embolden non-state actors across Asia. Militant groups in South and Southeast Asia including cells in Mindanao, southern Thailand, and parts of Myanmar may interpret the conflict as a religious duty. The risk of lone-wolf attacks or coordinated campaigns targeting Israeli or more likely any Western-linked interests in Asia will rise considerably.

This will in turn hit the tourism industry, a key sector in Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. In knock-on effect, foreign direct investment may slow if investors view the region as vulnerable to political or sectarian instability.

Cybersecurity experts are also warning of increased ‘hacktivism’ with pro-Iranian groups potentially targetting Israeli interests online.

Because of this, Asia must react – carefully. In an increasingly interdependent world, regional wars can spread like wildfire. The Iran-Israel conflict, should it escalate further, is no exception and will reach deep into East and Southeast Asia. Energy markets will convulse, political systems will be tested, and longstanding alliances may strain under pressure. As the Middle East stands on the brink, Asia must not look away. Its future, too, is at stake.

Features

South Korea, the US come together on nuclear deals

South Korean and US companies have signed agreements to advance nuclear energy projects, aiming to meet rising data centre power demands, support AI growth, and strengthen the US nuclear fuel supply chain.

World Bank seems to be having second thoughts about Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam

Ball now in Dushanbe’s court to justify high cost.

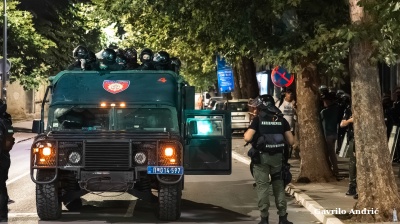

INTERVIEW: From cinema to Serbian police cell in one unlucky “take”

An Italian software engineer caught in Belgrade’s August protests recounts a night of mistaken arrest and police violence in the city’s tense political climate.

_Cropped_1756210594.jpg)

Turkey breaks ground on its section of the TRIPP rail corridor

Turkish project would help make TRIPP the go-to route for Middle Corridor freight.