Uzbekistan is preparing to become the third Central Asian country to have its own satellite in orbit.

In a June 6 interview with Kazakh media outlet Kazinform, the deputy director of Uzbekcosmos, Muhiddin Ibragimov, said Uzbekistan is looking to launch a satellite into space by 2028.

Ibragimov noted Uzbekistan is already in talks with Elon Musk’s SpaceX on organising the satellite launch. “Launch timelines are confirmed two to three years in advance, so it is crucial to conclude agreements and prepare technical specifications,” he said.

The Uzbekcosmos deputy chief also mentioned that Uzbekistan was preparing its own specialists in satellite technology. “Presently, seven [engineering] students from our country are working on master’s programmes at the Kyushu Institute of Technology in Japan,” Ibragimov said.

The students are studying design, assembly and preparations for satellites and should finish their programme in 2027, just ahead of the launch of the satellite.

Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan do not have their own satellites, but have communication service agreements with Kazakhstan and other partners to use transponder capacity.

Following in neighbours’ footsteps

Kazakhstan has put three communications satellites into orbit – KazSat-1, KazSat-2 and KazSat-3.

KazSat-1 launched in June 2006, but in 2008 began experiencing problems. By the end of that year, it was no longer responding to signals from Kazakhstan’s command centre.

KazSat-2 was launched in July 2011 and KazSat-3 in April 2014. KazSat-2 is still in use. KazSat-3 experienced battery problems in September 2023 and was reported lost.

All three satellites were launched from the Soviet-era, still-Russian-operated Baikonur Cosmodrome, a spaceport located in southern Kazakhstan.

The satellite buses of the first two KazSats, in other words the main bodies of the satellites, were constructed by Russia’s Krunishev State Research and Production Space Center. Russia’s Information Satellite Systems Reshetnev built the satellite bus for KazSat3.

A bne IntelliNews report in November 2022 said that Kazakhstan was working with Turkey to replace KazSat-3 with KazSat-3R.

Italian-French company Thales Alenia Space built the payloads for all three satellites.

Turkmenistan put a satellite in orbit 10 years ago. Its mission duration ends in 2030. Before then, the country plans to have a second satellite in space (Credit: Turkmen Telecoms, Turkmen Space Administration).

Turkmenistan launched its TurkmenAlem 52°E/MonacoSAT communications satellite in April 2015. Thales Alenia Space constructed the satellite bus. MonacoSAT, a joint venture involving Turkmenistan’s Ministry of Communications and National Space Agency and Space Systems International – Monaco, built the payload. A SpaceX rocket carried the satellite into orbit from Cape Canaveral.

Turkmenistan is planning on launching a second satellite before TurkmenAlem 52°E’s mission duration ends in 2030.

Tajikistan has no known plans to put a satellite of its own into orbit.

Kyrgyzstan, meanwhile, is receiving international attention as regards efforts spearheaded by a group of young women to build and launch Kyrgyz satellites.

A Nasa scientist is assisting the all-women Kyrgyz Space Program set up six years ago (Credit: Kyrgyz Space Program).

The all-women Kyrgyz Space Programme dates back to 2019. The programme has financial backing from various international organisations and support from Nasa scientist and aerospace engineer Camile Wardrop Alleyne.

Turkic satellites

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan signed an agreement in December 2021 on cooperation in space research and exploration during a visit paid by Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev to Kazakhstan.

Representatives of the two countries then met in the Kazakh capital Astana in September 2024 to discuss launching a set of satellites into space.

This publication reported in January this year that Uzbekcosmos’ Ibragimov announced plans to launch a satellite with the Organisation of Turkic States (OTS).

The OTS members are Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. They are all involved in the satellite project.

Turkmenistan is an OTS observer state, but has indicated several times that it will become a full member.

The OTS is aiming to launch its CubeSat scientific and technical satellite in 2026. Ibragimov mentioned in his interview with Kazinform: “At present, we are working together with our Kazakh colleagues on the assembly of the CubeSat satellite.”

Why is a satellite necessary?

For any country, having a national satellite in space brings a degree of prestige. Satellite technology is integral to communications structures of the modern world, and all governments want to be able to say their country has a satellite.

For the Central Asian governments, having their own satellite brings many benefits. Greater connectivity with remote areas, deployment in the monitoring of unfolding emergency situations, such as during earthquakes and wildfires, and analysis of the consequences of drought or flooding are some examples.

The most important gain, however, is better access to the internet.

Flicking the internet “kill switch”

Reliable and high-speed internet connections would be welcomed by most people in Central Asia still without them; however, it is control over internet access that is most important to their governments.

During various times of social upheaval, such as the “Bloody January” 2022 unrest in Kazakhstan, the violence in Tajikistan’s eastern Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) in May 2022, or, weeks later, the violence seen in western Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan Republic, the governments concerned have moved to shut down access to the internet in affected areas.

Kazakhstan has been in talks with SpaceX about using Starlink, but a major obstacle to agreement was the Kazakh insistence on having base stations in Kazakhstan that would allow the authorities to switch off internet service at will.

In late 2024, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Digital Development proposed a law that “prohibits the establishment and operation of communication networks within Kazakhstan if their control centres are based outside the country.”

The issue has apparently been resolved. The ministry said on June 12 that Kazakhstan’s public will be able to use Starlink from the third quarter of this year. Official consent was given to the launch, it added, after Starlink “agreed to comply with all requirements of our legislation in the field of information security.”

The ability to monitor internet use and have a “kill switch” to shut it down is surely a big part of why Turkmenistan has a satellite. Turkmen citizens have mobile phones and computers with internet access, but the authorities control the satellite communications services. They can impose a blackout at any time.

Uzbekistan’s announcement on its impending satellite launch is a sign of things to come. As things stand, there are only two operating satellites belonging to Central Asian nations. Including the OTS CubeSat, there will be four new Central Asian satellites in orbit by 2030.

Features

South Korea, the US come together on nuclear deals

South Korean and US companies have signed agreements to advance nuclear energy projects, aiming to meet rising data centre power demands, support AI growth, and strengthen the US nuclear fuel supply chain.

World Bank seems to be having second thoughts about Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam

Ball now in Dushanbe’s court to justify high cost.

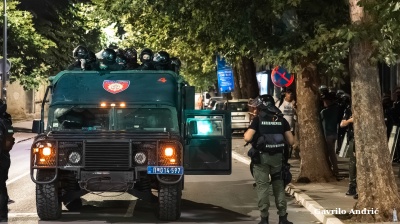

INTERVIEW: From cinema to Serbian police cell in one unlucky “take”

An Italian software engineer caught in Belgrade’s August protests recounts a night of mistaken arrest and police violence in the city’s tense political climate.

_Cropped_1756210594.jpg)

Turkey breaks ground on its section of the TRIPP rail corridor

Turkish project would help make TRIPP the go-to route for Middle Corridor freight.