Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe has fallen to its lowest level in five years, according to a new report by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw).

The drop is a sign of waning investor confidence amid global uncertainty and economic realignment. However, the report’s author, wiiw economist Olga Pindyuk, warns that in the longer term the region’s FDI-led growth model as a supplier to West European companies will come to an end.

Total FDI inflows into the region fell by around 25% in 2024 against the previous year, from approximately €100bn to just over €75bn. The downturn affected nearly all EU member states in the region, with Poland suffering a sharp 48% drop and Romania down 15%.

“The crisis in German industry and the uncertainty surrounding Donald Trump’s second term as US president clearly had a major impact on the region last year,” said Olga Pindyuk, economist at wiiw and author of the report.

The latest figures paint a grim picture. In the first quarter of 2025, the number of newly announced greenfield projects fell by 26% year on year, while capital commitments slumped by 55%. “This suggests that foreign investors currently have even less confidence in the region than they did at the beginning of the Covid crisis or the Russian invasion of Ukraine,” Pindyuk added.

German companies, historically the largest investors in the region, cut back their investment commitments by nearly half between Q2 2024 and Q1 2025 – down from €10.6bn to €5.4bn. The number of announced projects dropped 21% over the same period.

Austrian investors, who also maintain strong historical ties with the region, have been very cautious, though not altogether absent, said the report. Their capital commitments edged up slightly to €1.4bn, but the number of projects fell from 49 to 34.

“The region remains important for Austria and will continue to attract investment from there,” said Pindyuk. “However, given the country’s weak economy and the huge global economic uncertainties – such as Donald Trump’s policies – Austria’s investors are acting extremely cautiously,” she added.

There were a few notable bright spots. Czechia saw a 7.9% increase in foreign direct investment (FDI), while Croatia and Lithuania posted particularly strong gains of 38.7% and 28.8% respectively. Hungary also recorded modest growth of 5.1%, and Slovakia experienced a dramatic surge – roughly ten times higher than the previous year – largely driven by major one-off investments. These figures were partly influenced by large-scale projects, such as Chinese investments in electric vehicle and battery manufacturing facilities in Slovakia and Hungary.

The Western Balkans as a group also saw FDI rise by 17.4%, with Serbia and North Macedonia leading the way, and Turkey reported a 5.5% increase. Still, these individual gains did little to reverse the broader downward trend.

China remained the top source of newly announced investment projects in the region, despite a near 50% decline in capital commitments. Chinese companies pledged around €11.2bn over the past year – just ahead of Germany – but the figure marks a sharp retreat from previous highs.

“The sharp decline in Chinese capital commitments for new investments shows that in Eastern Europe even China’s trees do not reach the sky,” quipped Pindyuk.

Turkey and Poland emerged as the leading destinations for Chinese projects, with 12 new greenfield investments each over the past four quarters. However, most Chinese capital is being channelled to Turkey (34%) and Kazakhstan (26%), with Poland receiving just 3% of the total.

The report also highlights a broader structural shift: FDI is contributing less and less to growth across the region. The traditional model – heavily reliant on attracting foreign manufacturers, particularly in the automotive sector – is showing signs of strain.

“This points to structural change in the region, especially in those countries known for large direct investments in the manufacturing sector, and particularly in the automotive industry,” said Pindyuk.

“The Eastern European growth model, which has largely been based on attracting foreign direct investment, could therefore become obsolete in the medium term.”

wiiw has repeatedly urged countries to diversify away from the “extended workbench” role in Western supply chains and to invest instead in education, research and a tailored industrial policy to ensure long-term prosperity.

Features

South Korea, the US come together on nuclear deals

South Korean and US companies have signed agreements to advance nuclear energy projects, aiming to meet rising data centre power demands, support AI growth, and strengthen the US nuclear fuel supply chain.

World Bank seems to be having second thoughts about Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam

Ball now in Dushanbe’s court to justify high cost.

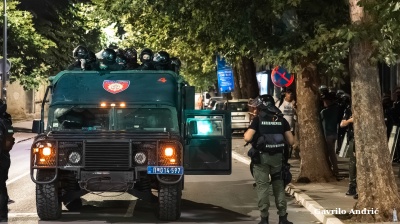

INTERVIEW: From cinema to Serbian police cell in one unlucky “take”

An Italian software engineer caught in Belgrade’s August protests recounts a night of mistaken arrest and police violence in the city’s tense political climate.

_Cropped_1756210594.jpg)

Turkey breaks ground on its section of the TRIPP rail corridor

Turkish project would help make TRIPP the go-to route for Middle Corridor freight.