In June, news emerged that the Russian gas giant Gazprom is finalising a plan to sell its Turkish assets, effectively exiting the Turkish domestic gas market. Gazprom will instead focus on its direct gas sales to Turkey, its second biggest export market. Its decision to exit the domestic market suggests that Gazprom has abandoned its ambition to become one of the biggest players in Turkey’s gas import and trading market.

According to Russia’s Kommersant, Gazprombank, a subsidiary of Gazprom, has finalised a deal to sell its 40% stake in the Turkish gas company Promak, a joint-venture between Gazprombank and the Turkish energy conglomerate Akfel Holding group, in which Gazprom also holds a direct minority stake. Gazprom will likewise sell the 71% stake it holds in Bosphorus Gaz, another Turkish gas importer and trader, to Turkey’s Sen Group.

While commercial concerns play a role in Gazprom’s potential exit (Bosphorus Gaz reportedly lost about €100mn last year, Gazprom has a number of disputes over gas prices in Turkey, and Akfel and Gazprom were rumoured to be far from amicable from day one), politics are also to blame. Alongside the weak lira and regulated tariffs, Gazprom’s Deputy Chairman Alexander Medvedev cited Turkey’s “unpredictability” and “the actions taken by the Turkish side with other private companies” as reasons behind Gazprom’s sale of Bosphorus Gaz.

Failed ambitions

In 2015 Gazprom had been set to control 16% of Turkey’s gas market, providing approximately 60% of gas imports in the country, according to Kommersant. In addition to its holdings in Promak and Bosphorus Gaz, Gazprom had ambitions to buy into Akfel Gas, a subsidiary of Akfel Holding. For unknown reasons, the Turkish competition regulator did not approve the deal. Less than a year later, even before Turkey’s downing of a Russian jet in November 2015, Gazprom had seemingly reassessed its Turkey strategy as it emerged that Gazprombank had also applied to sell its 40% share in Promak.

A year later in December 2016, the Turkish government seized control of Akfel Holding Turkey and replaced its board of directors. The government accused the company’s owners of having financed Turkish President Erdogan’s former ally, the US-based preacher Fethullah Gulen, whom Turkey accuses of having masterminded the coup attempt in July 2016.

With the sale of Gazprombank’s Promak share not yet complete, the nationalisation of Akfel Holding Turkey stalled the deal; it remains unclear what the nationalisation and board takeover means for Gazprom’s minority share in the Akfel parent company. Quoting Gazprom sources, media reported at the time that the nationalisation had left Gazprom and Gazprombank’s shares ‘in limbo’.

Now, with the Promak sale reportedly in its final stages, Gazprom is also selling Bosphorus Gaz. Although Gazprom is still weighing up its options in the country, its apparent exit reflects the concerns of foreign investors in Turkey where politics is increasingly affecting the business climate.

Wider impact

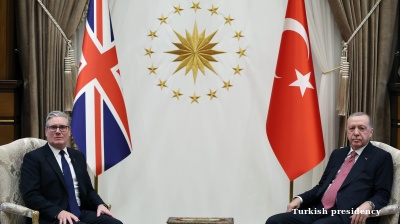

The uncertainty over the nationalisation of Akfel and Gazprom’s cited worries of political unpredictability is telling. A company that enjoys the backing of the Russian state and had likely received guarantees on the security of its investments is seemingly vulnerable to Erdogan’s domestic political agenda.

As of late June 2017, almost a year after the attempted coup, nearly 900 companies with combined assets of TRY 40.3 billion (US$11.3 billion) remained under government control. A number of these are partners of foreign companies.

The majority of these companies were transferred to Turkey’s Savings Deposit Insurance Fund since the attempted coup in July 2016. The purges – and the pressure applied to companies perceived to be sympathetic to Gulen – appear to have taken most foreign investors by surprise. But in hindsight the souring of the former alliance between Erdogan and Gulen provided a number of warning signs to investors.

Erdogan’s fallout with Gulen became public in late 2013; reshuffles in the judiciary in early 2014 signalled what was to come; and companies were targeted as early as 2015 – over a year before the coup attempt. Although the intensity of the Erdogan’s crackdown on the Gulen movement and its alleged sympathisers is unprecedented, the purges nonetheless were not surprising for long-time Turkey-watchers.

For instance, in May 2015, the government seized Bank Asya, a Turkish Islamic bank, which was then shut down in July 2016, days after the coup attempt. Similarly, the government effectively took over Koza Ipek Holding – which has a diversified portfolio of investments in mining, construction and tourism sectors – by appointing trustees to its management in October 2015, eight months prior to the attempted coup. At the time, Koza Ipek had investors from the US, UK, Luxembourg, Sweden and Canada, among others. Zaman, a pro-government newspaper that had turned critical of the government following Erdogan’s falling out with Gulen, was also seized in March 2016.

By using the attempted coup in July 2016 as justification to expand the crackdown, the government issued the state of emergency shortly afterwards, allowing it to seize companies by simply issuing decrees. The state of emergency has been already extended three times and Erdogan appears keen to extend it further. Purges, especially in the judiciary, academia and bureaucracy, are unlikely to stop.

Unsettling mood music

Despite statistics from the Turkish economic ministry indicating an increase in foreign direct investment and positive rhetoric from the government, we are seeing an uptick in investor concern over politics. Indicators such as the boost to Russian tourism and stronger than expected GDP growth (although some economists question whether growth is sustainable or the numbers are reliable), are overshadowed by the political situation. Concern has increased since Erdogan’s claim of a narrow victory in the April 2017 referendum. The country has not become a pariah state, but the mood music for investors is deeply unsettling.

Erdogan is focused on consolidating power in the run-up to the 2019 elections. Much-needed structural economic reforms, such as addressing issues in the labour market – that many hoped for following the referendum – are being delayed. There is also some speculation that elections could be brought forward; though in our view Erdogan is more likely to wait until 2019 (this could signal stability, allow parliament to enable his new political system, and maximise his time in power through term limits) the uncertainty on the timing is there.

In addition, the geopolitical situation is tenuous. One of Turkey’s most attractive features for investors – its relationship with the EU – is also a source for concern, due to the EU’s threat to suspend membership talks if the new presidential system is implemented.

An increasingly autocratic leader, a worsening clash between politics and business, and delicate foreign relations – as even the toughest of foreign companies, such as Gazprom, are finding, the Turkish market is fraught with difficulty. Turkey remains a large potential market, but it will be integral for companies to look beyond the government rhetoric and pay close attention to the political developments unfolding.

GPW Political Risk advises investors on political and economic risk and stakeholder engagement in Turkey, Iran, Russia, Central Asia and the Caucasus.

Opinion

COMMENT: Czechia economy powering ahead, Hungary’s economy stalls

Early third-quarter GDP figures from Central Europe point to a growing divergence between the region’s two largest economies outside Poland, with Czechia accelerating its recovery while Hungary continues to struggle.

COMMENT: EU's LNG import ban won’t break Russia, but it will render the sector’s further growth fiendishly hard

The European Union’s nineteenth sanctions package against Russia marks a pivotal escalation in the bloc’s energy strategy, which will impose a comprehensive ban on Russian LNG imports beginning January 1, 2027.

Western Balkan countries become emerging players in Europe’s defence efforts

The Western Balkans could play an increasingly important role in strengthening Europe’s security architecture, says a new report from the Carnegie Europe think-tank.

COMMENT: Sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil are symbolic and won’t stop its oil exports

The Trump administration’s sanctions on Russian oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil, announced on October 22, may appear decisive at first glance, but they are not going to make a material difference to Russia’s export of oil, says Sergey Vakulenko.

_Cropped_1761809941.jpg)