H ungary’s real estate sector has rebounded since 2014 after a difficult few years when the political uncertainty under Victor Orban’s first government followed swiftly on the heels of the international financial crisis. Today, Hungary is part of a wider Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) property boom, with the country’s strong economic growth buoying the real estate market.

ungary’s real estate sector has rebounded since 2014 after a difficult few years when the political uncertainty under Victor Orban’s first government followed swiftly on the heels of the international financial crisis. Today, Hungary is part of a wider Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) property boom, with the country’s strong economic growth buoying the real estate market.

"We are seeing now the after effects of the 'double whammy' that hit the property market in Hungary. First there was the financial crisis, which was most difficult in 2008 and 2009. Shortly after that in 2010 came the election of the first Orban government, which introduced a number of controversial policies, such as 'crisis taxes'. Some of those policies affected financial institutions which then stepped back from lending to property investors and developers," says David Dederick, managing partner of law firm Bird and Bird’s Budapest office.

"From 2008 to 2012, the market had frozen up and there was very little investment activity. Banks were not lending, new financial institutions were not coming in, and so those were some tough days for the real estate industry. Some major property groups such as Orco became insolvent or experienced financial difficulties," adds Dederick.

That started to change in 2014 when the smoke cleared and new investors began to arrive. The economies of CEE took off in about 2014, as bne IntelliNews reported in a recent cover story "CEE is booming". That has fed through into the real estate sector.

The political uncertainties after the election of Orban’s first government weren’t entirely a bad thing for investors willing to take a chance on the Hungarian market, as they gave rise to what some termed the "Orban discount". Like everywhere in CEE you get paid for taking risks.

But things really began to change for the better from 2014 onwards. With most investors standing on the sidelines at the start of the decade, the tide turned and interest built quickly.

"What you saw from the beginning of 2014 was the arrival of new investors, and renewed interest. Many such investors had not been active in the region prior to the crisis," says Dederick.

"From 2014, global players like Lone Star started to make very significant investments," he continues, citing the example of Lone Star’s acquisition of GTC, a regional development group listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, which is very active in all markets of the CEE region. "GTC was under significant financial pressure in the post-crisis period, so Lone Star could step in and buy a majority stake in the company on very good terms."

Business vs politics

Politics continue to be cause for concern in Hungary, not least because of the ongoing conflict between the Orban government and EU institutions.

Hungary has similar issues to Russia where there are two realities: things are good on "planet business" where the economy is recovering, incomes are rising, profits are improving and dividend yields are amongst the highest the world; however, on “planet politics” things are awful, a new Cold War has started, there is a military stand off and President Vladimir Putin is seen as an authoritarian.

Orban may be dismantling democracy in Hungary and getting away with it but he has delivered on strong economic growth and remains genuinely popular with the voters — the latest Fidesz supermajority delivered in the April 2018 general election was an assurance of political continuity. In addition, many of the more controversial changes were made in Orban’s first term in office, and the environment has become less perturbing for investors since then.

In economic terms, these are good times for Hungarians. GDP is expected to expand by 3.7% this year, inflation is a low 2.8% and unemployment is close to record lows of 4.4%.

"Currently, Hungary has a reasonably strong economy, and money coming in from the EU, a lot of which is going into infrastructure type projects that are also propelling the property sector. In Budapest, there are a number of speculative developments, with office complexes being built without pre-lets just on the strength of the market," says Dederick. "There is very strong demand, and rents are going up."

Prices are buoyant, the growth of the market is still in its early stages and developers have not caught up with demand, which is constraining supply. Still, Dederick says there are plenty of residential projects being developed and the hotel sector is strong too as there is room to catch up with Prague and Vienna – the benchmark cities for the hotel business in Central Europe.

The development of real estate is also being fuelled by the growing number of domestic investors getting into the business — not least the central and local governments.

"There is definitely robust interest in investment opportunities, both in quality and size, and that is something that will not change quickly. The pipeline takes time to catch up, which is why you see trends like office rents rising," says Dederick.

Features

Indian bank deposits to grow steadily in FY26 amid liquidity boost

Deposit growth at Indian banks is projected to remain adequate in FY2025-26, supported by an improved liquidity environment and regulatory measures that are expected to sustain credit expansion of 11–12%

What Central Asia wants out of the upcoming Washington summit

Clarity on critical minerals and a lot else.

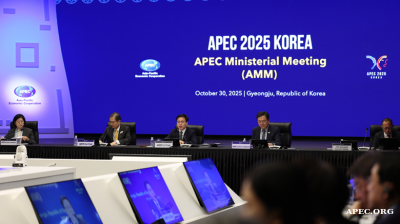

Global leaders gather in Gyeongju to shape APEC cooperation

Global leaders are arriving in Gyeongju, the cultural hub of North Gyeongsang Province, as South Korea hosts the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. Delegates from 21 member economies are expected to discuss trade, technology and security.

Project Matador marks new South Korea-US nuclear collaboration

Fermi America, a private energy developer in the United States, is moving ahead with what could become one of the most significant privately financed clean energy projects globally.